[Visual History of Korea] ‘Seonbi’ tradition defines Korean value system

By Korea HeraldPublished : Oct. 30, 2021 - 16:01

Educating intellectuals with knowledge, wisdom and character has long been the goal of Korean education throughout history.

Korean culture and history have been profoundly shaped by various religions and philosophies, but none has had as much lasting impact as Confucianism.

Confucianism before the Common Era and Neo-Confucianism after the 12th century have largely shaped the ruling class landscape of Korean kingdoms.

During the Goryeo Empire, scholars who were well learned possessing good character were called “seonbi.” The proper noun seonbi is synonymous with virtuous scholar and intellectual today.

Korean culture and history have been profoundly shaped by various religions and philosophies, but none has had as much lasting impact as Confucianism.

Confucianism before the Common Era and Neo-Confucianism after the 12th century have largely shaped the ruling class landscape of Korean kingdoms.

During the Goryeo Empire, scholars who were well learned possessing good character were called “seonbi.” The proper noun seonbi is synonymous with virtuous scholar and intellectual today.

Starting in the 10th century, “guageo” exams, equivalent to today’s civil service examinations, became the main path for the ruling “yangban” class men to navigate through government jobs.

While civil service exams today are a path of upward social mobility for all Koreans, no such egalitarian opportunities were available for Koreans until the 20th century.

While the guageo examinations were used to select candidates for the state bureaucracy, Korean intellectuals called seonbi, became entrenched in the national educational institutions called “seowon.”

The name Confucius was given by Jesuit missionaries in the late 16th century. His name is Kong Qiu, read as Gongja in Korean.

There is no worship of a single deity in Confucianism but Confucianism tradition is full of rituals, mostly surrounding the four human events: coming of age, marriage, funeral and the ancestral rites called “jesa.”

Confucianism is a pragmatic life solutions philosophy. Confucianism practices ancestor worship as a virtue. In Korean culture, Confucius is revered and remembered as a sage.

While civil service exams today are a path of upward social mobility for all Koreans, no such egalitarian opportunities were available for Koreans until the 20th century.

While the guageo examinations were used to select candidates for the state bureaucracy, Korean intellectuals called seonbi, became entrenched in the national educational institutions called “seowon.”

The name Confucius was given by Jesuit missionaries in the late 16th century. His name is Kong Qiu, read as Gongja in Korean.

There is no worship of a single deity in Confucianism but Confucianism tradition is full of rituals, mostly surrounding the four human events: coming of age, marriage, funeral and the ancestral rites called “jesa.”

Confucianism is a pragmatic life solutions philosophy. Confucianism practices ancestor worship as a virtue. In Korean culture, Confucius is revered and remembered as a sage.

“Confucianism is not a religion that worships ancestors, rather it is an indigenous belief system of revering the ‘Heaven, Land and People as One.’ This belief became more concrete with rules, rituals and procedures during the Yin Dynasty (Shang) which was founded by Gojoseon people,” said Yi Ki-hoon, the author of “Dongyi Korean History.“ Dongyi people, who invented the oracle bone scripts, the first draft of Hanja characters, lived in the Shandong Peninsula in eastern China, sharing common heritage with ancient Joseon.

Korean ancestor worship rituals are designed to commemorate and venerate the spirits of deceased forebears on annual remembrance day and on holidays. The Confucian notion of filial piety kicks in and people remember ancestors as if they were still living in the same household.

In fact, it was rather common for people to celebrate the ancestor remembrance rituals for up to four generations before them. ”The belief was that it takes about 120 years, four generations, for the spirit to leave the loved ones,“ said Korean philosopher Kim Young-oak.

Education and ceaseless lifelong learning defines Korean seonbi tradition. Seonbi is an intellectual whose sense of purpose comes from his belief in his virtues. Hence seonbi is also often called a virtuous scholar and called a “teacher” after their passing.

Korean ancestor worship rituals are designed to commemorate and venerate the spirits of deceased forebears on annual remembrance day and on holidays. The Confucian notion of filial piety kicks in and people remember ancestors as if they were still living in the same household.

In fact, it was rather common for people to celebrate the ancestor remembrance rituals for up to four generations before them. ”The belief was that it takes about 120 years, four generations, for the spirit to leave the loved ones,“ said Korean philosopher Kim Young-oak.

Education and ceaseless lifelong learning defines Korean seonbi tradition. Seonbi is an intellectual whose sense of purpose comes from his belief in his virtues. Hence seonbi is also often called a virtuous scholar and called a “teacher” after their passing.

At the Byeongsanseowon Confucian academy, one of the nine Korean seowon listed on the UNESCO’s Memory of the World, jesa for Ryu Seong-ryong, the chief state councilor of Joseon in 1592 during the Japanese invasion, is held in the third and ninth month. The rites are attended by members of Byeongsanseowon and Ryu’s descendants.

The annual fall ceremony which ran for two days this year was only attended by elderly men and no women.

“Confucianism is often incorrectly associated with discrimination against women. Men and women just have different roles,” said Kim Tae-gyun, 89, the head of Byeongsanseowon.

The annual fall ceremony which ran for two days this year was only attended by elderly men and no women.

“Confucianism is often incorrectly associated with discrimination against women. Men and women just have different roles,” said Kim Tae-gyun, 89, the head of Byeongsanseowon.

“One of the challenges is that we’re doing away with our old traditions. Even in my family, we are no longer celebrating four generations of ancestors, instead, only three. Too many of our young family members are living away in cities,” said Kim.

To understand Koreans and why they do what they do is to understand their adherence to their values.

Korean people’s value system in the 21st century has a foundation in the teachings of Confucianism, more accurately in Neo-Confucianism.

One of the key features of Neo-Confucianism is placing great emphasis on “blind adherence to principle,” said Yoo Pil-hwa, a professor at the Sungkyunkwan University Graduate School of Business, during the Yeongju Culture Summit this week.

The goal in the traditional Korean value system is to become a seonbi, a learned sage, an intellectual with knowledge, wisdom and character.

Seonbi, the intellectual elite during the Joseon Dynasty, who made up the ruling yangban class were all educated through public academies called seowon.

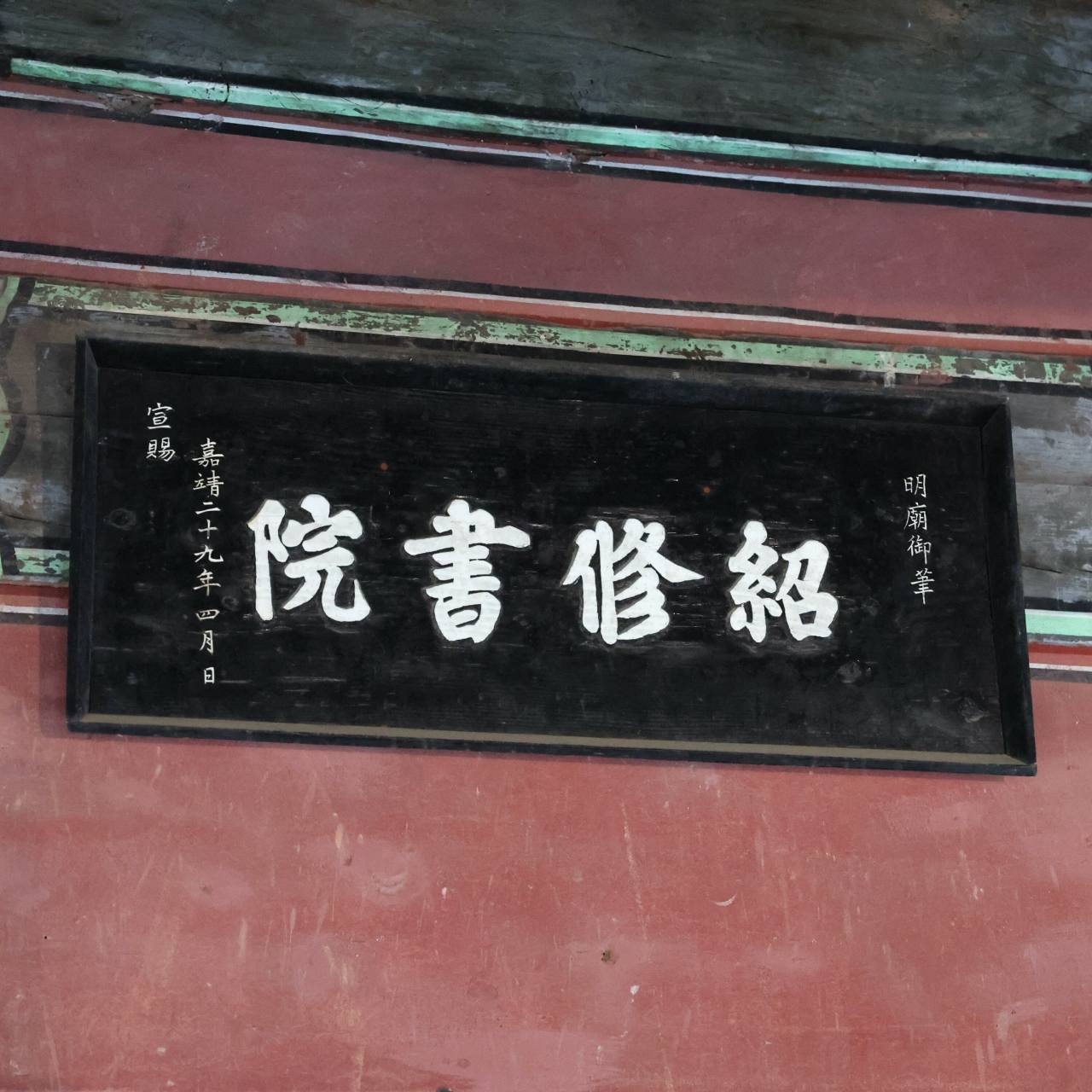

Sosuseowon, the oldest seowon in Korea, was established during the Joseon Dynasty in Yeongju City, North Gyeongsang Province.

To understand Koreans and why they do what they do is to understand their adherence to their values.

Korean people’s value system in the 21st century has a foundation in the teachings of Confucianism, more accurately in Neo-Confucianism.

One of the key features of Neo-Confucianism is placing great emphasis on “blind adherence to principle,” said Yoo Pil-hwa, a professor at the Sungkyunkwan University Graduate School of Business, during the Yeongju Culture Summit this week.

The goal in the traditional Korean value system is to become a seonbi, a learned sage, an intellectual with knowledge, wisdom and character.

Seonbi, the intellectual elite during the Joseon Dynasty, who made up the ruling yangban class were all educated through public academies called seowon.

Sosuseowon, the oldest seowon in Korea, was established during the Joseon Dynasty in Yeongju City, North Gyeongsang Province.

A function of seowon was to honor significant teachers with remembrance rites and Sosuseowon honors Ahn Hyang (1243-1306), who introduced Neo-Confucianism to Korea.

Seowon around the country became a magnet for producing learned intellectuals and politicians whose unending political rivalry during the 500-year Joseon Dynasty turned bloody many times.

When King Sejo (1417-1468), the son of King Sejong the Great, became the 17th king of Joseon in 1455 after the overthrowing of his nephew Danjong, the fallout from that coup d’etat led to the order of Danjong’s death in 1457. It came after a massacre of hundreds of Danjong followers at Sosuseowon in 1453.

Danjong was the only Joseon King not to have a proper funeral when he was killed by poison while in exile.

Adhering to the Korean Confucian tradition of honoring the dead, Danjong was given a proper royal funeral in May 2007, 550 years after his death.

By Hyungwon Kang (hyungwonkang@gmail.com)

-----

Korean American photojournalist and columnist Hyungwon Kang is currently documenting Korean history and culture in images and words for future generations. -- Ed.

Seowon around the country became a magnet for producing learned intellectuals and politicians whose unending political rivalry during the 500-year Joseon Dynasty turned bloody many times.

When King Sejo (1417-1468), the son of King Sejong the Great, became the 17th king of Joseon in 1455 after the overthrowing of his nephew Danjong, the fallout from that coup d’etat led to the order of Danjong’s death in 1457. It came after a massacre of hundreds of Danjong followers at Sosuseowon in 1453.

Danjong was the only Joseon King not to have a proper funeral when he was killed by poison while in exile.

Adhering to the Korean Confucian tradition of honoring the dead, Danjong was given a proper royal funeral in May 2007, 550 years after his death.

By Hyungwon Kang (hyungwonkang@gmail.com)

-----

Korean American photojournalist and columnist Hyungwon Kang is currently documenting Korean history and culture in images and words for future generations. -- Ed.

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[Graphic News] More Koreans say they plan long-distance trips this year](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/17/20240417050828_0.gif&u=)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240419100350)

![[From the Scene] Monks, Buddhists hail return of remains of Buddhas](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050617_0.jpg&u=20240419175937)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240419100350)

![[Today’s K-pop] Illit drops debut single remix](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050612_0.jpg&u=)