[Eye Interview] Creating universe with small square canvases

Artist Kang Ik-joong combines lyrics of Arirang, moon jars filled with children’s art to express hope for unification

By Kim Hoo-ranPublished : June 19, 2020 - 10:00

The great disruptor. The COVID-19 pandemic has been raging around the world since the beginning of the year, claiming lives, crippling economies and laying bare the great inequalities that divide the world. The new coronavirus has directly or indirectly impacted our lives.

For New York-based artist Kang Ik-joong, the lockdown has been a time for contemplation. “We don’t know where we are exactly,” Kang said during an interview with The Korea Herald on June 12 in Seoul. He had arrived two weeks earlier for the installation of “Gwanghwamun Arirang,” a public art installation marking the 70th anniversary of the Korean War, which was unveiled June 15.

“I have sorted out where I am at,” Kang said. The forced isolation was an opportunity to stop, take a pause and look around. “When we are in constant motion, we cannot see what is happening outside (of ourselves),” he said.

He continued to work at home with materials he had on hand, and also took the opportunity to clean up the studio.

In isolation, one is alone, but not really alone, Kang observed. The expression “social distancing” is a misnomer, Kang pointed out. “Actually, there is more engagement. We are physically distancing, but we are emotionally more connected and socially engaged,” he said.

“Gwanghwamun Arirang” is a cube measuring eight meters in length, width and height, which features two major motifs in Kang’s works -- moon jars and 3 inch (7.62 centimeter) by 3 inch Hangeul letter blocks. On all four sides, the moon jars are filled with 12,000 3-inch-by-3-inch drawings by children from the 23 nations that took part in the Korean War on South Korea’s side. The moon jars are surrounded by Hangeul letter blocks that spell out the lyrics to “Arirang,” a popular traditional Korean folk song. The cube also features the names of 175,801 fallen soldiers of the Korean War.

“Hangeul and moon jar are a code word for unification, a union, becoming one life,” Kang said, explaining how a vowel and a consonant make up a sound and how a moon jar is created by attaching the two separately made parts -- the upper half and the lower half -- in the middle. Likewise, the lower and upper halves of “Gwanghwamun Arirang” rotate 90 degrees every 70 seconds, the moon jars dividing and becoming whole.

The installation work, commissioned by the Ministry of Patriots and Veterans Affairs, is placed in Gwanghwamun Square, in front of Gwanghwamun, the main gate to Gyeongbokgung, a Joseon era royal palace until the end of June, after which is will be moved to a more permanent location.

While several candidate sites were discussed, Kang decided on Gwanghwamun Square. “It is like the country’s navel. It is also a place of communication between the past, the present and the future,” Kang said, referring to the site’s central location. “It is like a real gate. It is a borderline that doesn’t belong anywhere,” he said.

Small canvases, big pictures

Kang, who went to the US in 1984 to study at the Pratt Institute in New York City, began using 3-inch-by-3-inch canvases, for which he has become best known, out of practical necessity. As an art student juggling studies and work to support himself, he was always short of time. Carrying around the small canvases, he was able to work on his art whenever there was time to spare.

Did he start out thinking that the small canvases would become so “big”? “No. It was initially for sketching. My thought was to transfer the sketches to larger canvases,” he said. He thinks he must have painted more than 100,000 such canvases.

He also has more than a million 3-inch-by-3-inch drawings by children collected for his public art projects, such as “100,000 Dreams” (1999) and “The Bridge of Dreams” (2013), Those drawings have been scanned for posterity, as have drawings by some 4,000 persons displaced during the Korean War. “They contain the thoughts, the dreams that people have. These are spiritual heritage of the 21st century,” Kang said, adding that he plans to publish them in a book form. “They are a window to the future,” he said.

An important process in Kang’s public art is public participation. To elicit participation, the artist needs to engage in dialogue with the people, “persuading, explaining and listening,” Kang explained.

“We must listen to them. People displaced by the Korean War cry as they draw. Children understand the present through drawing about the future and the elderly understand the present through the past,” he said.

Kang, who has published two books of poetry and pictures, “Moon Jar” and “Sarubja,” said he paints as he writes poems. “I don’t really revise. And the more I do, the better it gets. It is important to ride the rhythm,” he said. Defining painting as a learning process, Kang said his purpose in drawing and writing is to discern the order of the world. “I think I get a glimpse of that in children’s drawings.”

In fact, children’s works are central to many of his works, including the yet-to-be realized project, “The Bridge of Dreams,” a floating circular bridge over the Imjin River that divides the Korean Peninsula into South Korea and North Korea. As envisioned, it would feature 1 million drawings from the two Koreas as well as those who have been displaced during the Korean War.

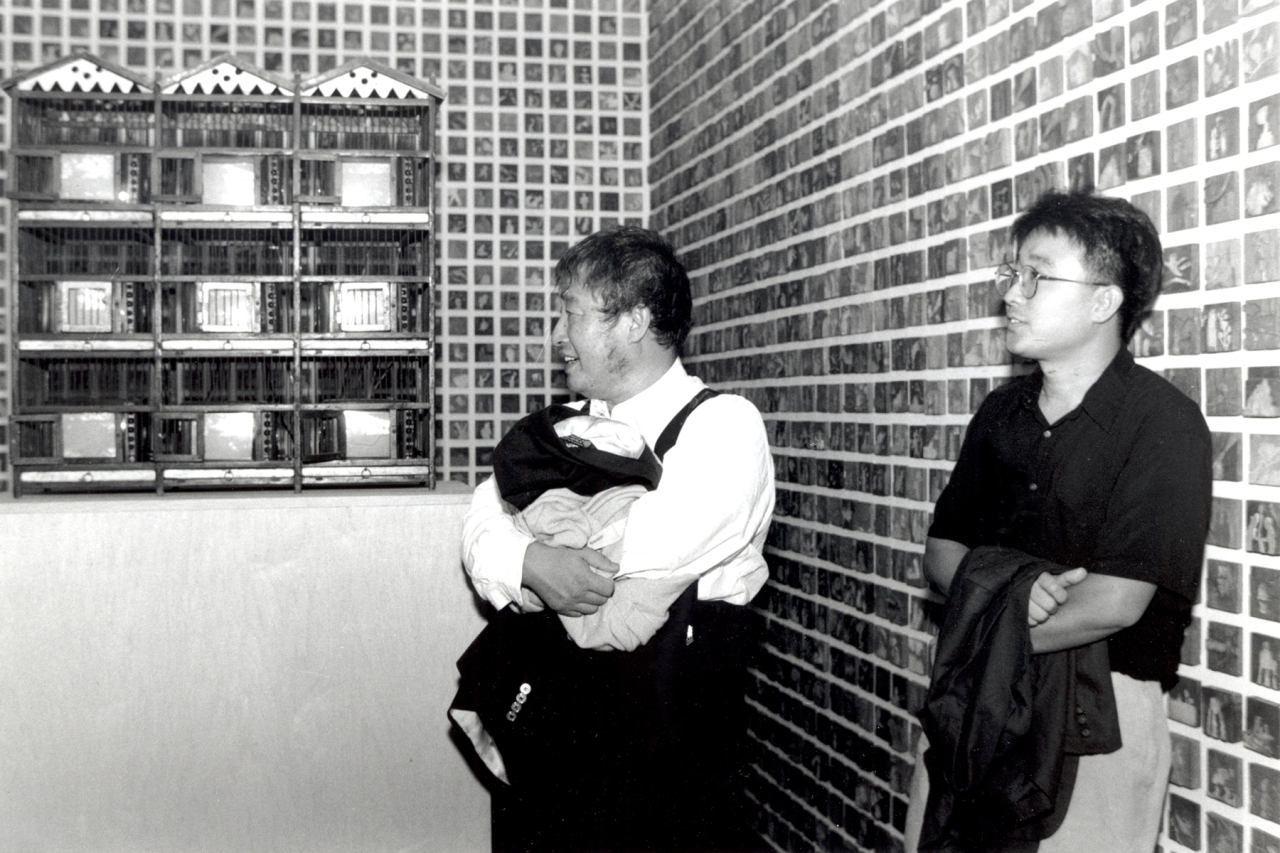

Asked about his breakthrough moment, the winner of numerous awards, including the Special Merit prize at the 1997 Venice Biennale, cites “Happy World,” his Princeton Public Library project in Princeton, New Jersey, as a project that made him feel good.

After a local newspaper ad went out seeking donations of objects from residents, some 1,000 people lined up on a Saturday to donate items dear to them. “I mixed the objects and my paintings and the library saw a tenfold increase in attendance, with 3,000 visitors daily. “It was a successful case of community building through art,” he said.

On the role of the artist, he waxed philosophical. “Artist is a person who casts a fishing net. Scientist is a person who hauls it in, economist a person who divides up the catch and politician a person who distributes it,” Kang said. “Artist is important.”

By Kim Hoo-ran (khooran@heraldcorp.com)

![[KH Explains] How should Korea adjust its trade defenses against Chinese EVs?](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/15/20240415050562_0.jpg&u=20240415144419)

![[Today’s K-pop] Stray Kids to return soon: report](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/16/20240416050713_0.jpg&u=)