[Anniversary Special] 21 years after ‘Japanese invasion,’ Korean pop culture stronger than ever

By Yoon Min-sikPublished : Aug. 14, 2019 - 14:23

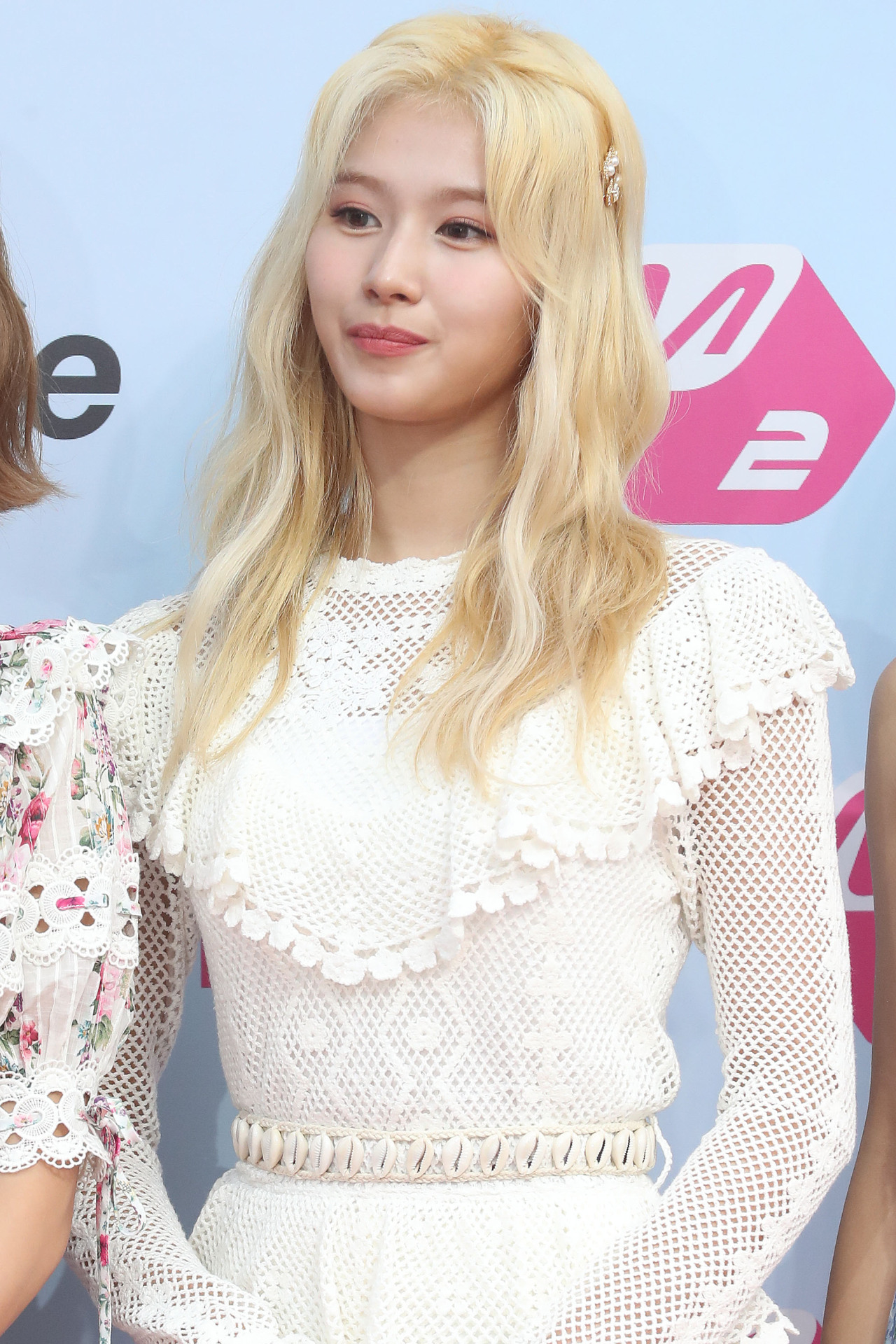

JYP Entertainment said Monday that Twice has received platinum certification in the Japanese market for its fourth and fifth singles, meaning the girl group has sold at least 250,000 copies of every single released in the country.

Since South Korea opened its gates to Japanese pop culture in 1998, the two countries have exchanged cultural content. But over the past years, South Korea has been more successful in selling its content to Japan than vice versa.

Since South Korea opened its gates to Japanese pop culture in 1998, the two countries have exchanged cultural content. But over the past years, South Korea has been more successful in selling its content to Japan than vice versa.

According to the Korea Creative Content Agency, annual exports of Korea’s music industry to Japan recorded $320 million in 2017, accounting for 62.5 percent of music exports. In contrast, Korea only spent $3 million buying music-related content from Japan.

In terms of all cultural content, Korea exported $1.38 billion worth of content to Japan in 2016 while importing only $151 million worth of content from the country.

These figures show that Seoul has been dominating its neighbor in the cultural content market. Even the recent diplomatic row between the two countries, which has led to a nationwide boycott of Japanese goods here, has failed to hinder the success of Korean groups in Japan.

It has not always been that way, as opening up the market to Japan had been compared with opening Pandora’s Box at the turn of the millennium.

Ban on Japanese culture

Prior to 1998, Japanese cultural content had been strictly restricted or forbidden. This stemmed from hostilities arising from Japan’s 1910-1945 colonization of the peninsula, during which Japan attempted to root out Korean culture, including a ban on the use of Korean language, which was depicted in the 2019 period film “Mal-Mo-E: The Secret Mission.”

The two countries’ attempts to normalize diplomatic ties began under the helm of Korea’s first President Syngman Rhee, but floundered for over a decade until the controversial 1965 agreement that excluded an apology by Japan for colonization of the peninsula.

Even then, the Korean public showed discomfort toward Japanese culture.

In 1964, Dong-A Ilbo published an article titled “Japanese style spreads,” comparing the influx of Japanese culture to a “new form of invasion of (Japanese) imperialism.”

It raised concerns over the revival of Japanese influence in the country after 3 1/2 decades under Japanese rule.

Children’s animations were among the very few Japanese content aired on TV, but even that was heavily censored for anything that reminded viewers of the country. All names and nationalities were changed to prevent Korean children from rooting for Japanese characters.

“Dash! Yonkuro,” a Japanese manga-turned-animation about miniature car racers, was aired in Korea between 1994 and 1996, but the version here was very different form the original. Any scene that had traces of Japan were cut out, including those with the protagonist’s kimono-wearing grandmother. In one episode, the team goes on a training trip at a site with an old Japanese warship, but it was changed to a Chinese warship.

Nevertheless, Japanese cultural products garnered fans in South Korea, particularly in large cities and geographically close Busan, where some youngsters grew fond of the culture picked up through Japanese TV and radio broadcasts that reached the area.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Nintendo dominated the global video game market with its plump Italian plumber, and Korea’s fledgling market was no exception. Arcades all across the country were flooded with teenagers mashing buttons to Street Fighter games, while at home they spent hours playing Super Mario.

Japanese culture was seeping through. It was only a matter of time before the flood would rush in.

Japanese invasion

Seoul officials were not blind to this issue, holding governmental working-level meetings to discuss cultural exchange with Japan since 1983.

Amid the trend of globalization, the deeply-rooted grudge -- fueled by controversial comments by Japan, including its claim of Korean islets of Dokdo -- stood as an obstacle.

Winds of change began to blow when presidential candidate Kim Dae-jung mentioned possibly opening up to Japanese cultural content in 1997, a process that he kick-started the next year upon taking office. In 1998, a breakthrough in the two country’s relationship came when Emperor Akihito of Japan mentioned Japan had inflicted “great pain upon those living in the Korean Peninsula.”

After Kim’s visit to Japan, Korea decided to immediately allow partial imports of Japanese video content, including movies and manga, a move that expanded over the next few years.

As of now, most cultural content from Japan is allowed, except a large portion of TV shows, such as dramas, comedies and variety TV shows, and music videos in Japanese language.

At the time, there were concerns that the inflow of Japanese culture would overpower Korea’s home-grown content. Even now, Japan has the second-largest music market in the world, estimated to be worth over $5.7 billion, more than six times bigger than Korea’s ($945 million).

Some fields, such as animations, took a serious hit. But Korea continued to thrive in areas like music and movies, outpacing its neighbor in some instances.

For example, Japanese manga “Old Boy” -- not really one of the most popular comic books, even in Japan -- was remade into a highly praised film, “Oldboy,” by Park Chan-wook, which completely overshadowed the original material.

Korean content going strong

Twice, Blackpink and BTS are not the only successful Korean products that have landed in Japan.

The aforementioned KOCCA report shows that exports of Korean video game content to Japan came to $600 million in 2016, about 12 times the $50 million the country spent importing Japanese game content. The figure for comic books and movies are roughly similar, but Korean is selling more than buying in terms of cultural content.

A significant trend in the cultural sector is that there is much less open hostility toward Japanese culture just because it is Japanese.

Despite the ongoing spat between the two countries, Japanese band Cornelius still took the stage at the recently held Incheon Pentaport Rock Festival 2019.

At the initial stage of the boycott on Japanese products, some netizens bashed Japanese members of Twice and IZ*ONE, but this movement was soon squashed out by a majority of the public. Girl group Rocket Punch -- which has a Japanese member -- debuted as scheduled last week.

While there is no telling when the standoff between Seoul and Tokyo will end, cultural exchange between the two countries appears to be going strong -- a phenomenon unimaginable two decades earlier.

By Yoon Min-sik (minsikyoon@heraldcorp.com)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240418181020)

![[Today’s K-pop] Zico drops snippet of collaboration with Jennie](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050702_0.jpg&u=)