[Feature] Workers more likely to call out abuse in wake of 2016 candlelight vigils

7 in 10 workers say they experienced workplace harassment in 2017: survey

By Kim Bo-gyungPublished : March 17, 2019 - 15:56

Reflecting the common Korean expression “My monthly paycheck includes the cost of excessive criticism and emotional labor,” widespread verbal and emotional bullying in the workplace has risen as a social issue in the wake of revelations of chilling office harassment by chief of WeDisk Yang Jin-ho in 2018.

In late 2018, the Labor Standards Act, which legally defines and bans office bullying, was amended in response to growing calls for regulations to stop widespread misbehavior at work and punish businesses that turn a blind eye to bullying.

Experts attribute the change in atmosphere that has younger-generation employees increasingly choosing to stand up to office bullying and address issues head-on to the massive candlelight protests in late 2016 that led to the impeachment of former President Park Geun-hye.

“Between 2016 and 2017 South Korea experienced critical political changes, where citizens brought about change by voicing their opinions via candlelight vigils. The experience gave people a boost in confidence to stand up for their rights in everyday life, starting at the office where we spend the majority of our time,” Oh Jin-ho, an official of civic organization Gapjil 119, told The Korea Herald.

One impact of the mass protests and the subsequent impeachment of the president is the change in what has become seen as virtue. “We have moved from the traditional ‘top-down, no questions asked’ workplace culture to an environment where it is acceptable to speak out. This is also seen in the skyrocketing number of posts on the Cheong Wa Dae petition website,” Oh added.

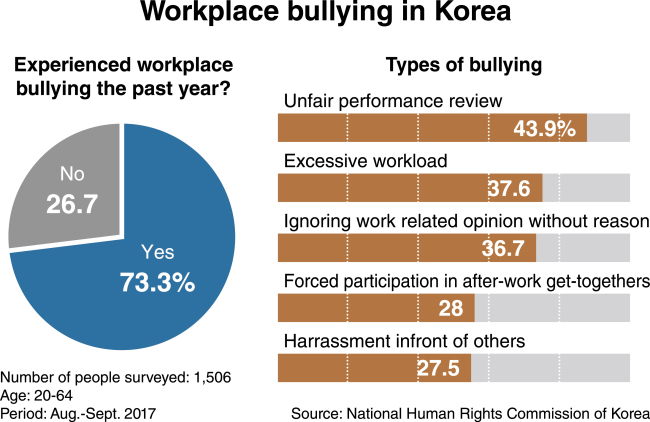

Though the vast majority of reports of workplace harassments are not as severe as the case of Korea Future Technology Chairman Yang Jin-ho -- who faces six charges, including rape and violation of the Animal Protection Law for allegedly forcing workers to catch chickens with a Japanese knife and arrows -- 73.3 percent of 1,506 workers in a 2017 National Human Rights Commission of Korea survey said they experienced office bullying.

Unfair performance reviews topped the list of harassment at 43.9 percent, followed by excessive workload at 37.6 percent, 28 percent for forced participation in after-work events such as dinners and physical violence at 7.6 percent, according to the survey.

A media industry worker in her 30s surnamed Lee recalls suffering from nausea due to emotional and verbal abuse by her boss last summer, mainly for refusing to attend after-work gatherings.

“I personally don’t enjoy drinking, yet I was forced to drink and have fun at after-work get-togethers. It was emotionally and physically dreadful,” said Lee.

“My boss would point to me to enliven the mood, and when I didn’t, he’d scold and humiliate me in front of the whole team. The emotional and verbal abuse would continue in a mobile messenger chat room and I would be given excessive workload.”

Lee requested a one-on-one meeting with her manager to address the issue in hopes of finding middle ground. Nothing changed and she moved to a different company with a smaller paycheck but with the promise of strict office hours.

“I had thought about taking the issue to the Labor Ministry, but I’ve seen a few cases in which the whistleblower’s identity was revealed. Plus my boyfriend and family told me not to create a scene before leaving the company. Now I am highly satisfied with my life,” Lee said

Her case would be categorized as office bullying according to the guidelines for office bullying issued by the Ministry of Employment and Labor last month. The guidelines were created to help distinguish the fine line between mistreatment and intensive work.

The ministry’s guidelines give a few examples of workplace bullying.

For instance, appointing an employee, who returns from parental leave, to a lower rank position and pressuring fellow teammates to alienate the person while using offensive language is recognized as office bullying, according to the guideline.

Repeatedly forcing junior staff to schedule after-hours drinks and spend part of their bonus to treat seniors, and making them write an official apology when they refuse to do so is another case of harassment.

According to the revised Labor Standards Act, companies with more than 10 employees are required to implement measures to prevent and deal with workplace harassment by July 16 and report them to the Labor Ministry. Companies that do not comply will be fined up to 5 million won ($4,400).

Critics, however, have called into question the effectiveness of the amendment that does not specify punishments. Individual companies have to decide punishments for those found guilty of workplace bullying.

“There are two loopholes in the revision. One is the absence of legal punishment for bullying by the owner, and the other is that it does not guarantee anonymity,” said Oh.

The revision defines and bans workplace harassment, and states that companies that dismiss or unfairly reassign a victim for reporting bullying would face up to three years behind bars or 30 million won in penalties. There is no provision for punishing the perpetrator.

Addressing the complaints, Rep. Han Jeoung-ae of the ruling Democratic Party of Korea proposed a partially revised act last month that would punish perpetrators with up to two years of jail time and 20 million won.

“After Yang Jin-ho’s case broke, I received many complaints asking for legal ways to punish perpetrators of office harassment in the office,” Han said.

Some managerial level workers express concerns and confusion about the amount of workload and personal conversations deemed acceptable.

“I don’t know what to talk about with my team anymore besides the weather, which is not going to help me understand them better. In my defense, it’s only natural for me to want to keep close the workers who I am comfortable assigning work to and who I can share a personal bond with,” said Park, a team manager at a conglomerate.

With changing workplace dynamics, there is expected to be greater emphasis on “soft skills.”

“It was difficult to define the extent of office bullying. Times have changed, so senior employees have to be more sensitive about language use and treatment of junior workers. Overall, soft skills are going to become an ever more important trait in the office,” said a Labor Ministry official who worked on the guidelines.

By Kim Bo-gyung (lisakim425@heraldcorp.com)

![[Kim Seong-kon] Democracy and the future of South Korea](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/16/20240416050802_0.jpg&u=)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240418181020)

![[Today’s K-pop] Zico drops snippet of collaboration with Jennie](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050702_0.jpg&u=)