Forgetting is bliss, but not always

Author of ‘White Chrysanthemum’ talks about debut novel on victims of Japan’s wartime sexual slavery

By Shim Woo-hyunPublished : April 25, 2018 - 17:14

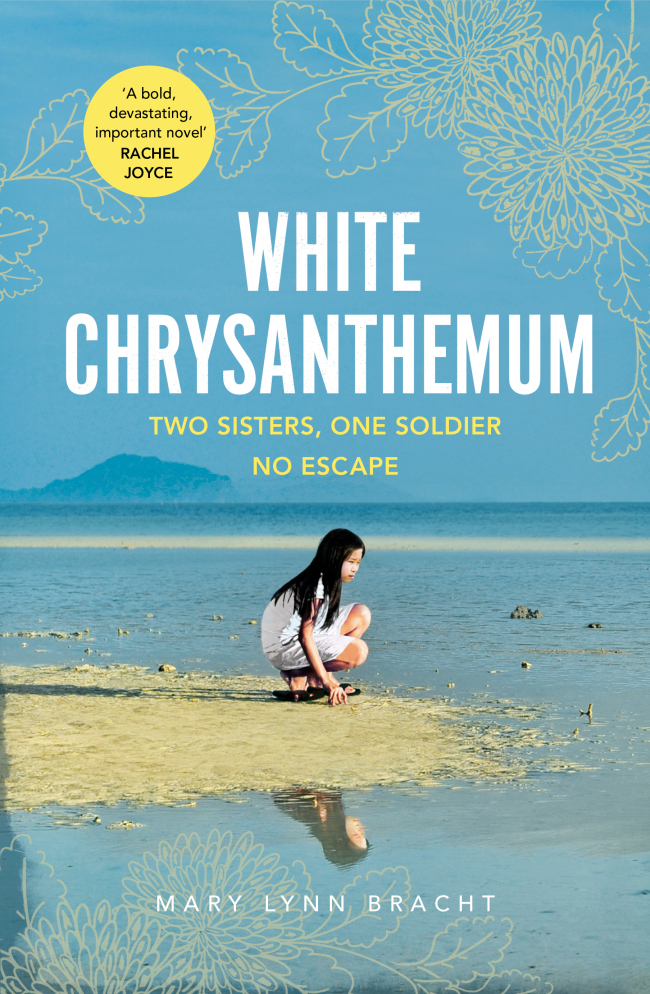

”White Chrysanthemum“

By Mary Lynn Bracht

Chatto & Windus Books (320 pages, $18.11)

One of the victims of Japan’s wartime sexual slavery passed away Monday at 97. Choi Duk-nye‘s death brings the number of known surviving victims to 28. So far this year, four victims of Japan‘s wartime sexual slavery, including Choi, have passed away.

The generation of wartime victims will soon all be gone, as will the people who carry the memories of suffering under Japanese occupation. After one generation and another, the individual and collective memories that people have long pledged to honor may gradually fade away.

Published in January this year, Mary Lynn Bracht’s “White Chrysanthemum” is her debut novel that resists such forgetting. Her novel strives to bring back memories that must not be forgotten.

“White Chrysanthemum” alternates between the narratives of two Korean sisters. Through the chapters of Hana, who is abducted by Japanese soldiers and forced into sexual slavery during the war years, Bracht reveals an individual story of one of the euphemistically labeled “comfort women.” Bracht also offers her reflection on how the tragic past has shaped the survivors through the chapters of Emi in 2011, Hana’s sister who constantly looks to the past from present-day Seoul.

Forgetfulness sometimes can be bliss. As Friedrich Nietzsche said, “Blessed are the forgetful for they get the better even of their blunders.” If the past is something painful or bothersome to be reminded of, we may be best to think of it never again.

However, there are cases where obliviousness cannot be justified. There are certain pasts we must not fail to remember. Some pasts, we have to remember to not repeat.

“White Chrysanthemum” is a novel that renews the tragic past and commands readers to never forget.

Following is an excerpt from The Korea Herald‘s interview with Bracht.

The Korea Herald: Why did you choose the “comfort women” as the subject of your debut novel? And why were you drawn into such a political issue?

Mary Lynn Bracht: After nearly 30 years of activism, the continued denial of reparations and justice by the Japanese government drew me to their plight. I found it difficult to imagine what it must be like not only to survive the horror of military sexual slavery, but then to have to fight for justice for decades with no resolution in sight. Meanwhile, these women are dying from old age and illness, and may soon disappear from history. They have been denied justice overwhelmingly because they are women and the crimes committed against them are sexual in nature. I hoped that by telling their story in an intimate way, following one young girl and detailing the systematic abuse and torture she was forced to endure, a tragic part of Korean history would reach people around the world who have yet to learn of the plight of the hundreds of thousands of women trafficked for sex in World War II.

KH: The novel appears to be based on many cultural and historical details, and the reading list of 38 books at the end shows you did a lot of research. What measures did you take in your research?

Bracht: Researching for this book was a varied and often intense undertaking. The testimonies of the women who came forward were documented in numerous online articles, published essays, books, anthologies, government records and documentary films. The information had been out there for anyone to read since the 1990s, yet so few people in the West had heard about the “comfort women.” I checked the sources and bibliographies within articles and anthologies for further texts, finding them in the British Library and the libraries in Birkbeck College and the School of Oriental and Asian Studies. This initial research took six months to a year, and then I also took another year to research WWII, the Korean War, the haenyeo (Jeju Island’s female divers) and Mongolia while I was writing the first and second drafts.

KH: What were the most difficult parts of the writing process?

Bracht: The most difficult part of the whole writing process was finding the best way to convey the story so that the reader experiences it and lives through it with the characters. I wanted the reader to experience the injustices both Hana and Emi suffered and to feel the emotional turmoil they endured. Finding the best way to achieve this took a long time before I ever wrote the first word. I had to dream up Hana and decide who she was, how she thought, what her strengths and motivations were, where she started from and where she would end up -- all before I could begin writing. When Hana became defined as a real person I could relate to, then I knew I was ready to tell her story. Emi’s character came much later in the writing, but I went through the same process before I could begin to write her story. It was imperative to find the right voice for each of the sister’s storylines if I wanted to achieve my goal to take the reader on a journey into two lives separated by a terrible war and to feel their fears and pain.

KH: Why did you choose to deal with the two stories of Hana and Emi at the same time? Is Hana‘s story an allegory for readers?

Bracht: When writing Hana’s story, Emi grew into a character in her own right because I felt it was important to convey the consequences suffered by the family members left behind. Emi’s entire life changed the moment Hana was taken away. She lost her innocence, like her sister Hana, and Emi became an important reminder of the guilt felt by those who survived tragedy.

Hana’s story, while specific to Korean women during World War II, is not unique today. Sexual slavery is still happening. Women and girls all over the world are still forced into sexual slavery by warring men (e.g. Boko Haram, the Islamic State group) and by the illegal sex industries in the Middle East, India, Asia, Europe and America all preying on vulnerable young women and girls. I wanted Hana to represent all the victims of sex trafficking, historically and in modern times, with the hope that her story will add to the conversation on sex trafficking and help survivors. Unfortunately, the burden of sexual violence is often placed upon the victims, while the perpetrators elude justice. Like the “comfort women,” the women who survive trafficking today will continue to suffer from injustice, lifelong mental/health issues, post-traumatic stress disorder and ostracization from their families, communities and societies, who see them as “soiled,” willing participants in their own victimization.

KH: As the book revolves around a political issue, it could be read differently depending on the reader’s nationality or ethnicity. What do you expect from Korean readers?

Bracht: Korean readers have been aware of the issues surrounding the “comfort women” for a long time, and I think their familiarity regarding the subject will take away any shock factor experienced by Western readers learning of this dark period in Korean history for the first time. I hope Korean readers will find in “White Chrysanthemum” a story of sisterhood and familial bonds that rings true. I also hope to give voice to the importance of kindness, especially during extraordinary circumstances, like war and the struggle for survival. It takes so little effort to extend kindness, which has the possibility to forever alter a person’s life.

KH: The book resonates as it is about a similar power dynamic as that today. How do you feel about the ongoing #MeToo movement here in South Korea?

Bracht: The #MeToo movement is so important for women globally, and I have so much support for South Korean women demanding to be heard. Sexual violence against women has been ignored for too long. Male perpetrators have been protected from prosecution by their fame, wealth and status, forcing their victims into silence and often continued victimhood. The #MeToo movement empowers women of all walks of life by giving them a platform to be heard and believed, especially since traditional methods have failed so many women. It’s a first step, one of many more to follow.

By Shim Woo-hyun (ws@heraldcorp.com)

![[Kim Seong-kon] Democracy and the future of South Korea](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/16/20240416050802_0.jpg&u=)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240418181020)

![[Today’s K-pop] Zico drops snippet of collaboration with Jennie](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050702_0.jpg&u=)