[Feature] Senior NK defectors struggle in job market

By Jung Min-kyungPublished : Aug. 6, 2017 - 15:07

“Our wish is unification, even in our dreams.”

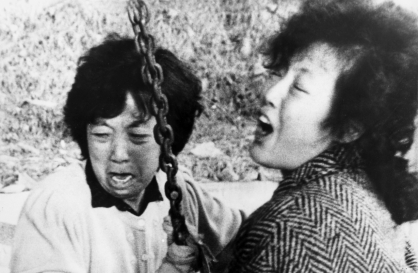

A group of elderly people sang in unison, while neatly placing envelopes in plastic wrapping. Gathering here at an assistance center in Nowon, northeastern Seoul, were defectors from North Korea training for basic job skills to help them survive in the capitalistic world that is South Korea.

A group of elderly people sang in unison, while neatly placing envelopes in plastic wrapping. Gathering here at an assistance center in Nowon, northeastern Seoul, were defectors from North Korea training for basic job skills to help them survive in the capitalistic world that is South Korea.

But chances for them to land a decent job, or even the menial, low-paying jobs that most defectors end up with, are not very high. About 40 percent of the defector population of 30,000 in South Korea are jobless, said Kim Hee-bong, manager of the Korea Hana Foundation’ defector self-reliance support team.

Senior defectors are perhaps the least privileged group in the country’s fiercely competitive job market. On top of the many handicaps that usually comes with the tag of being a North Korean defector, such as language barrier, cultural differences, and social discrimination, older ones have age and health issues and tend to be slow learners.

“Most of them suffer from some form of illness -- it’s mainly due to malnutrition in the North, and disabilities they suffered while crossing the inter-Korean border,” said Kim.

To alleviate the issue, state-run defector aid agencies such as Hanawon and Kim’s Hana Foundation are running facilities and programs to help them lead a financially independent life. The Nowon assistance center is one such facility.

Seo Yoo-jung, the chief manager of the center who is a defector herself, said defectors face hardships in adjusting to a capitalist economy. Seo supervised the first senior job training program at the center when it opened in July.

“In North Korea, we are told what to do -- work there doesn’t require as much creative thinking as it does here,” Seo said.

“The language is also different here, which is why defectors experience difficulties even while serving in restaurants. It’s challenging to communicate with customers here.”

According to Seo, most defectors lack office skills, which forces them to take basic jobs in the service sector, such as restaurant servers. Also, they believe office work here is too rigorous and competitive by their standards.

A male defector in his 60s participating in the job program in Nowon was forced to accept the harsh reality, but stressed that being jobless was not what he aimed for.

“The work culture in South Korea took a toll on me both physically and mentally,” a defector surnamed Han said. “But staying at home (without a job) was much worse.”

To bring down the barrier, Hanawon has been providing funds to defectors willing to enter and complete its 500-hour job training program since 2005.

Women, especially single mothers who risked their lives to bring their children to the South with them, are also suffering from the lack of jobs here. Government data shows that 70 percent of the defector population are women.

“I came to South Korea eight years ago with my daughter and son,” said a female defector in her 40s, who requested anonymity.

“Foreigners who work here have the freedom to visit their motherland, but we don’t. I find companionship at the center where I can talk with my fellow defectors from my home country,” she tearfully said.

North Korean defectors earn an average of 1.5 million won ($1,350) a month, which amounts to just about 67 percent of South Korea’s average monthly wage of 2.3 million won, according to data released by the National Assembly Budget Office in 2016.

Financial hardships are among the biggest difficulties they face here. In a 2015 government survey of 12,000 defectors, 20.9 percent of the group had suicidal thoughts at least once after their arrival in South Korea, 6.8 percentage points higher than South Koreans. About 30 percent stated financial hardships as the main reason.

By Jung Min-kyung (mkjung@heraldcorp.com)

![[Today’s K-pop] BTS pop-up event to come to Seoul](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/17/20240417050734_0.jpg&u=)

![[Graphic News] More Koreans say they plan long-distance trips this year](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/17/20240417050828_0.gif&u=)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240419100350)