Your life is comfy compared to the hell of the North Korean border

By KH디지털2Published : Aug. 17, 2016 - 14:22

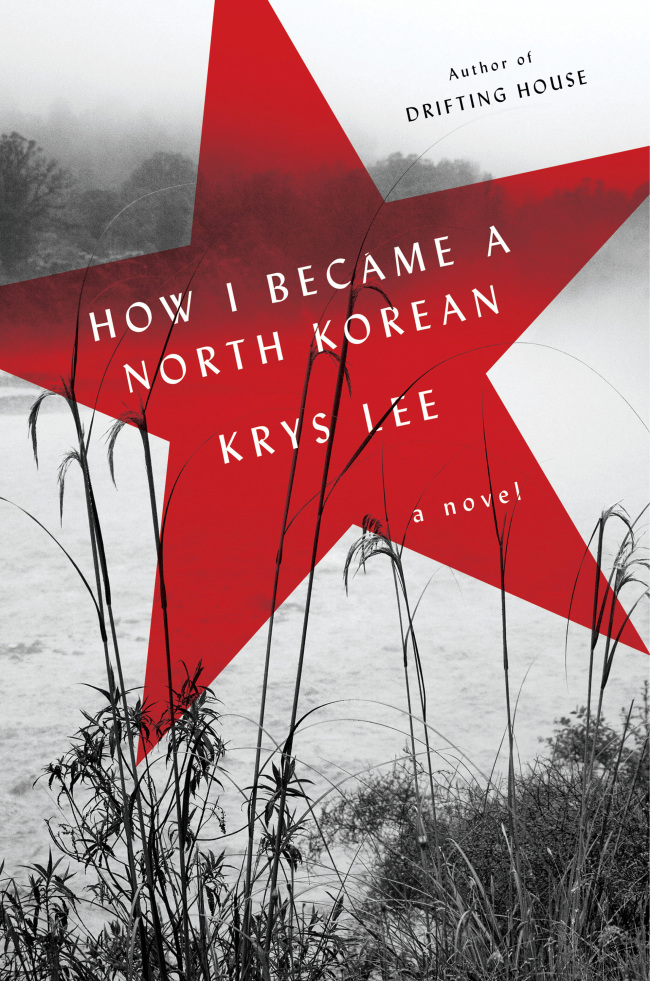

“How I Became a North Korean”

By Krys Lee

Viking (244 pages, $27)

Forgetting the complexities of other lives is so easy these days, immersed as we are in our daily grinds, our political battles, our iPhones and our Netflix. With her devastating yet ultimately hopeful first novel, Krys Lee provides the reminder that sometimes we need a wakeup call. “How I Became a North Korean” demands that we look outside ourselves, pay attention and bear witness to the world and how it can break so many of us.

In the stories of her first book, “Drifting House,” Lee -- an assistant professor of literature and creative writing in Seoul, South Korea -- explored questions of country and identity, past and future, in North and South Korea, as well as in the United States. In “How I Became a North Korean,” she narrows her focus to a single place: China, along its border with North Korea, where three young people cross paths after escaping their homelands.

Like many such places, this border is dangerous and desperate, especially for North Koreans, who are regarded at best with suspicion and at worst with outright antagonism.

Lee’s narrators have arrived there in 2009 with different baggage, divergent pasts. Unlike most of his countrymen, Yongju, once the pampered son of loyalist parents in the North Korean capital of Pyongyang, has not known hunger or deprivation. He and his sister have grown up on bootleg DVDs and foreign novels. But his father’s betrayal of the Dear Leader -- in the powerful and startling opening chapter of the book, which deftly sets the tone to come -- forces Yongju, his mother and young sister to flee the city and cross the river into China, where a gruesome fate all too often awaits women.

Jangmi, on the other hand, was weaned on the deprivations of North Korea’s great famine, and she has been scrambling for survival since childhood. She has relied on trading sex for survival, and now, pregnant and determined to get out of North Korea to save her baby, she agrees to an arranged marriage in China. She hopes her new husband won’t realize the bad timing of the infant’s arrival, but her plans are threatened by his spoiled, jealous daughter.

Jangmi, though, understands how to survive: “I closed my eyes as one person, opened them as another. Somewhere inside of me there was another self that was hidden from sight. She was watching this other woman. … ”

Religious Danny and his parents emigrated from the Autonomous Korean Prefecture in China when he was 9, but now, a miserable and bullied gay teenager in California, he wants to return to China, where his mother is doing missionary work. After a couple of ugly incidents his father agrees to send him, but after discovering his mother’s secret, Danny flees from her apartment.

The three meet, and as they try to evade authorities who will send them home, Lee shines a harsh light on the treatment of North Korean immigrants in this foreign world. The result is eye-opening and heartbreaking, even if Danny’s story seems a bit far-fetched. Would a relatively timid son of America, even one born in China, risk his life and run away in such a way? But Lee uses Danny’s higher position in the cultural hierarchy to underscore the vast injustice and hopeless predicaments of the some 50,000 North Korean immigrants hiding along China’s border, people most of us didn’t know existed until now.

Readers of Adam Johnson’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel “The Orphan Master’s Son” should relish this revelation of yet another facet of North Korean life. “How I Became A North Korean” doesn’t quite reach that novel’s mighty scope, but it’s an intense, unforgettable, compassionate study of human resilience. “A person can get used to almost anything in order to survive,” Jangmi says. “That was what China taught me.” What Lee teaches us is that there is hope in the most desperate of circumstances, that the human spirit can still sputter to life after the worst has happened. (TNS)

By Connie Ogle

Miami Herald

![[Graphic News] More Koreans say they plan long-distance trips this year](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/17/20240417050828_0.gif&u=)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240419100350)

![[From the Scene] Monks, Buddhists hail return of remains of Buddhas](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050617_0.jpg&u=20240419175937)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240419100350)

![[Today’s K-pop] Illit drops debut single remix](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050612_0.jpg&u=)