Korean teens fight for rights to birth control, sex life

By Claire LeePublished : April 11, 2016 - 16:47

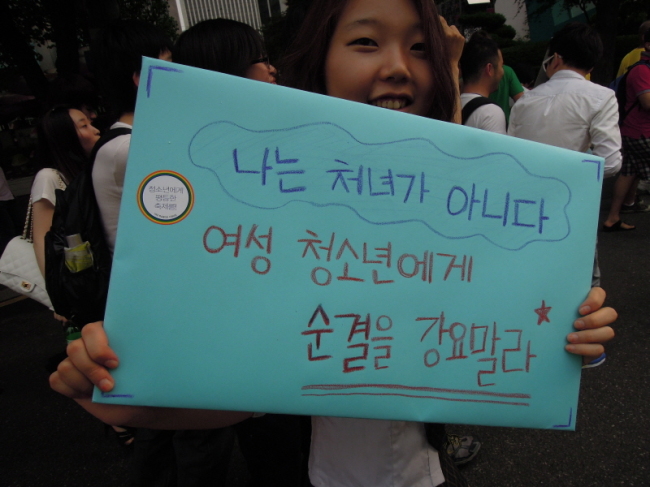

In 2012, when Kang Min-jin was 17 years old, she decided to go public about her sex life. Back then, in a rally focusing on youth rights in Seoul, she held a banner which she thought was both deeply personal and political. It said: “I’m not a virgin (and I’m a teenager).”

“Yes, it was a political statement,” she said in an interview with The Korea Herald. “When you live in a country where you can be punished at school for dating a fellow student, where you need to be 19 or older to get information about birth control online, nothing can be more political than what I said that day.”

“Yes, it was a political statement,” she said in an interview with The Korea Herald. “When you live in a country where you can be punished at school for dating a fellow student, where you need to be 19 or older to get information about birth control online, nothing can be more political than what I said that day.”

Now 20, Kang is a college student and a member of an advocacy group that fights for teenagers’ rights, including their rights to birth control, privacy and quality sex education in South Korea. She and her colleagues also fight for teenagers’ rights not to be physically punished at school as well as to be able to dress freely, and actively -- and safely -- engage in sexual and romantic relationships as minors.

As of 2014, only 39 percent of sexually active South Korean teenagers used birth control, while 66.1 percent of all teenagers who became pregnant had abortions. The nation’s sex education, which often discourages students from dating but does not provide enough information on birth control, is highlighted as one of the main reasons behind such statistics.

“Korean teenagers are often seen as property belonging to their parents,” she said. “We want teenagers to be acknowledged as independent beings who can make their own decisions about their lives, their bodies and their relationships.”

No-dating rule for students

According to Kang’s organization, the Group for Youth Sexuality Rights, almost half of all Korean high schools nationwide have a policy that bans dating in school. At the same time, a lot of schools -- many in provincial areas -- separate boys and girls by placing them in different buildings or classes. Some of them even have different mealtimes so they will not run into each other during lunch breaks. They also ban students from dying their hair, wearing earrings as well as altering the hemline of school uniform skirts, according to the organization.

“One of the students who reported her case to us said she and her boyfriend, a fellow student, were kicked out of her dorm after she was caught holding hands with him on a surveillance camera,” Kang said.

Despite these measures, South Korean schoolchildren still date. According to research by the state-run Aha Sexuality Education and Counseling Center for Youth, about 60 percent of all South Korean teenagers have dated at least once from 2004-2013. As of 2014, 5.3 percent of all South Korean schoolchildren have had sex. While it is legal for minors aged 19 or under to purchase birth control, one needs to be 19 or older in South Korea to have full access to information regarding contraception such as condoms on the search engine Naver.

“Developing romantic feelings for someone as a teenager is just a natural part of growing up,” said Park Hyun-ee from the ASECCY. “Instead of banning dating, it is necessary to educate them on what to expect and how to protect themselves when they engage in sexual relationships. They should be also educated on the responsibilities they have for their romantic partners as well as consequences of unprotected sex.”

South Korea’s Gender Ministry last year made a controversial decision to ban teenagers from buying “specialized condoms,” such as those with studs. Naver banned those aged 19 or under from viewing the complete search results for the word “condoms” as the term inevitably collects information on such types of condoms as well.

While there is no medical proof that such condoms can damage the health of minors, Kim Sung-byuk, a Gender Ministry official who oversees youth policies, said the products may trigger “abnormal and unhealthy views” on sex among schoolchildren. “As we have said many times before, all teenagers are allowed to purchase condoms as long as they are not the specialized kinds,” he said. “We have filed requests to Naver to allow teenagers to access more information on safe products.”

‘Why I lied that I was raped’

Kang was 15 when she had her first sexual experience. She had quit middle school in Ulsan as she had become weary of the physical punishment that was occurring daily in her class. “I was a good student, as in I did well academically. So I was rarely punished. But I think witnessing your friends being punished was equally traumatizing,” she said. “We would be hit for reasons like being late, talking loudly in class, or dozing off while the teacher was talking. One of the teachers had a habit of choking children whenever she was angry.”

She recalls the desire to be acknowledged as an independent human being -- “like an adult” -- when in school. “I think that’s why I became interested in sexual relationships,” she said. “That was the only kind of relationship in which I was treated like a grown-up, not a child or a property.”

Yet during her first experience, she said she was not able to tell her partner, to use protection. “I just didn’t know when to say it, and how to say it.”

At the time, as she was scared that she might become pregnant, Kang decided to purchase emergency contraceptive pills. While she had learned about the pills during sex education class in school, she had not been told where and how she could purchase them.

“I didn’t know all teenagers were allowed to get a doctor’s prescription for the pills as long as they visit clinics and pay for it,” she said. “So I lied to my doctor that I had been raped. And really, no teenager nowadays should be as confused as I was when trying to get information on birth control.”

Forced abortions, adoptions

On top of lacking information on birth control, Kang said that pregnant teenagers are often forced to make decisions that they do not want to make, such as abortion or giving their babies up for adoption.

One of the teens who reported her case to Kang’s organization was drugged by her mother when she was pregnant and was taken to a clinic where she underwent abortion illegally against her will. When she woke up, the procedure was already over.

Choi Hyung-sook, who used to be an unwed single mother, witnessed a similar case while working as a sex education teacher for teens. When a high school student became pregnant with her boyfriend, a fellow student, the two ran away to the countryside, as her parents had tried to force her to have an abortion. The young couple wanted to keep the baby and had plans to raise the child together. Yet when she arrived in a hospital to give birth, health care workers contacted her parents. They were following laws that aim to protect minors. When the baby was born, the teen’s mother sent the child for adoption overseas without her daughter’s consent.

“Many school teachers I met have repeatedly said students are supposed to study, and students are not supposed to date, as if teenagers don’t need to learn anything about birth control,” Choi told The Korea Herald. “Should teenage mothers – who were never fully educated on birth control options -- be forced by their own parents to give up their children just because they are minors? It’s something that we should really think about.”

Abortion is illegal in South Korea except in certain circumstances, such as when the woman was impregnated by rape.

Park Hye-young, the associate director of Sunflower Center, a state-run support institution for victims of sexual violence, said that the center receives many pregnant teenagers who claim to have been raped and ask the center to support the cost of their abortion procedures.

“There have been cases where the young women were not raped,” she said. “They just became pregnant because they had unprotected sex and were not educated enough about birth control. They would visit our center after learning that only rape victims are eligible to receive government support for safe, legal abortion procedures.”

Kang said teenagers who keep their pregnancies a secret from their parents, as well as those who ran away from homes, are especially vulnerable under the current legal system.

“When you are a teenager and you don’t have the money and the right information, the chances are you may end up receiving an unsafe abortion procedure by an uncertified doctor,” she said. “The (current) sex education fails to educate teenagers on birth control, and the current laws fail to protect them from unsafe abortion. It’s like a vicious circle.”

As of 2014, only 39 percent of sexually active South Korean teenagers used birth control, while 66.1 percent of all teenagers who became pregnant had abortions. The nation’s sex education, which often discourages students from dating but does not provide enough information on birth control, is highlighted as one of the main reasons behind such statistics.

“Korean teenagers are often seen as property belonging to their parents,” she said. “We want teenagers to be acknowledged as independent beings who can make their own decisions about their lives, their bodies and their relationships.”

No-dating rule for students

According to Kang’s organization, the Group for Youth Sexuality Rights, almost half of all Korean high schools nationwide have a policy that bans dating in school. At the same time, a lot of schools -- many in provincial areas -- separate boys and girls by placing them in different buildings or classes. Some of them even have different mealtimes so they will not run into each other during lunch breaks. They also ban students from dying their hair, wearing earrings as well as altering the hemline of school uniform skirts, according to the organization.

“One of the students who reported her case to us said she and her boyfriend, a fellow student, were kicked out of her dorm after she was caught holding hands with him on a surveillance camera,” Kang said.

Despite these measures, South Korean schoolchildren still date. According to research by the state-run Aha Sexuality Education and Counseling Center for Youth, about 60 percent of all South Korean teenagers have dated at least once from 2004-2013. As of 2014, 5.3 percent of all South Korean schoolchildren have had sex. While it is legal for minors aged 19 or under to purchase birth control, one needs to be 19 or older in South Korea to have full access to information regarding contraception such as condoms on the search engine Naver.

“Developing romantic feelings for someone as a teenager is just a natural part of growing up,” said Park Hyun-ee from the ASECCY. “Instead of banning dating, it is necessary to educate them on what to expect and how to protect themselves when they engage in sexual relationships. They should be also educated on the responsibilities they have for their romantic partners as well as consequences of unprotected sex.”

South Korea’s Gender Ministry last year made a controversial decision to ban teenagers from buying “specialized condoms,” such as those with studs. Naver banned those aged 19 or under from viewing the complete search results for the word “condoms” as the term inevitably collects information on such types of condoms as well.

While there is no medical proof that such condoms can damage the health of minors, Kim Sung-byuk, a Gender Ministry official who oversees youth policies, said the products may trigger “abnormal and unhealthy views” on sex among schoolchildren. “As we have said many times before, all teenagers are allowed to purchase condoms as long as they are not the specialized kinds,” he said. “We have filed requests to Naver to allow teenagers to access more information on safe products.”

‘Why I lied that I was raped’

Kang was 15 when she had her first sexual experience. She had quit middle school in Ulsan as she had become weary of the physical punishment that was occurring daily in her class. “I was a good student, as in I did well academically. So I was rarely punished. But I think witnessing your friends being punished was equally traumatizing,” she said. “We would be hit for reasons like being late, talking loudly in class, or dozing off while the teacher was talking. One of the teachers had a habit of choking children whenever she was angry.”

She recalls the desire to be acknowledged as an independent human being -- “like an adult” -- when in school. “I think that’s why I became interested in sexual relationships,” she said. “That was the only kind of relationship in which I was treated like a grown-up, not a child or a property.”

Yet during her first experience, she said she was not able to tell her partner, to use protection. “I just didn’t know when to say it, and how to say it.”

At the time, as she was scared that she might become pregnant, Kang decided to purchase emergency contraceptive pills. While she had learned about the pills during sex education class in school, she had not been told where and how she could purchase them.

“I didn’t know all teenagers were allowed to get a doctor’s prescription for the pills as long as they visit clinics and pay for it,” she said. “So I lied to my doctor that I had been raped. And really, no teenager nowadays should be as confused as I was when trying to get information on birth control.”

Forced abortions, adoptions

On top of lacking information on birth control, Kang said that pregnant teenagers are often forced to make decisions that they do not want to make, such as abortion or giving their babies up for adoption.

One of the teens who reported her case to Kang’s organization was drugged by her mother when she was pregnant and was taken to a clinic where she underwent abortion illegally against her will. When she woke up, the procedure was already over.

Choi Hyung-sook, who used to be an unwed single mother, witnessed a similar case while working as a sex education teacher for teens. When a high school student became pregnant with her boyfriend, a fellow student, the two ran away to the countryside, as her parents had tried to force her to have an abortion. The young couple wanted to keep the baby and had plans to raise the child together. Yet when she arrived in a hospital to give birth, health care workers contacted her parents. They were following laws that aim to protect minors. When the baby was born, the teen’s mother sent the child for adoption overseas without her daughter’s consent.

“Many school teachers I met have repeatedly said students are supposed to study, and students are not supposed to date, as if teenagers don’t need to learn anything about birth control,” Choi told The Korea Herald. “Should teenage mothers – who were never fully educated on birth control options -- be forced by their own parents to give up their children just because they are minors? It’s something that we should really think about.”

Abortion is illegal in South Korea except in certain circumstances, such as when the woman was impregnated by rape.

Park Hye-young, the associate director of Sunflower Center, a state-run support institution for victims of sexual violence, said that the center receives many pregnant teenagers who claim to have been raped and ask the center to support the cost of their abortion procedures.

“There have been cases where the young women were not raped,” she said. “They just became pregnant because they had unprotected sex and were not educated enough about birth control. They would visit our center after learning that only rape victims are eligible to receive government support for safe, legal abortion procedures.”

Kang said teenagers who keep their pregnancies a secret from their parents, as well as those who ran away from homes, are especially vulnerable under the current legal system.

“When you are a teenager and you don’t have the money and the right information, the chances are you may end up receiving an unsafe abortion procedure by an uncertified doctor,” she said. “The (current) sex education fails to educate teenagers on birth control, and the current laws fail to protect them from unsafe abortion. It’s like a vicious circle.”

To protect or to be free

Conservative activists, on the other hand, support the government’s method of restricting teenagers from being exposed to sex so as to minimize the risk that follows.

Lee Kyung-ja, who heads Student First, a grouop of Korean parents, said public sex education should discourage students from having sex, instead of educating them on birth control options.

“We’ve had students who were traumatized after attending such classes that taught about birth control options in detail. They’d come home and say they were scared and shocked,” she told The Korea Herald.

“We think sex education should focus on responsibility and self-control. I believe all schoolchildren eventually learn about sex naturally. We don’t have to (unnecessarily) provoke or shock them by informing them too much, by educating them on things like how to use condoms or homosexuality.”

But advocates of liberal sex education contend that it is closely linked to protecting students’ basic rights.

“The school system is very oppressive,” Kang said. “You are constantly competing against one another, while often separated from the other gender. You are not supposed to date or have sex. You are only supposed to study and your only goal should be achieving good grades. It’s almost inhumane.”

The activist said she hopes to see more Korean teens making independent and educated choices on birth control and romantic relationships. “Even as adult women, we are told that it’s our right to say no (to unwanted sexual activities),” she said. “But we rarely get reminded that it is also our right to say yes -- and enjoy and exercise one’s sexual self-determination to the widest possible sense.”

Meanwhile, Kang continues to hand out stickers with a message taken from a song to show that teenagers are also free to love. They say: “It’s really the best age to fall in love.”

By Claire Lee (dyc@heraldcorp.com)

Conservative activists, on the other hand, support the government’s method of restricting teenagers from being exposed to sex so as to minimize the risk that follows.

Lee Kyung-ja, who heads Student First, a grouop of Korean parents, said public sex education should discourage students from having sex, instead of educating them on birth control options.

“We’ve had students who were traumatized after attending such classes that taught about birth control options in detail. They’d come home and say they were scared and shocked,” she told The Korea Herald.

“We think sex education should focus on responsibility and self-control. I believe all schoolchildren eventually learn about sex naturally. We don’t have to (unnecessarily) provoke or shock them by informing them too much, by educating them on things like how to use condoms or homosexuality.”

But advocates of liberal sex education contend that it is closely linked to protecting students’ basic rights.

“The school system is very oppressive,” Kang said. “You are constantly competing against one another, while often separated from the other gender. You are not supposed to date or have sex. You are only supposed to study and your only goal should be achieving good grades. It’s almost inhumane.”

The activist said she hopes to see more Korean teens making independent and educated choices on birth control and romantic relationships. “Even as adult women, we are told that it’s our right to say no (to unwanted sexual activities),” she said. “But we rarely get reminded that it is also our right to say yes -- and enjoy and exercise one’s sexual self-determination to the widest possible sense.”

Meanwhile, Kang continues to hand out stickers with a message taken from a song to show that teenagers are also free to love. They say: “It’s really the best age to fall in love.”

By Claire Lee (dyc@heraldcorp.com)

![[Exclusive] Korean military set to ban iPhones over 'security' concerns](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050599_0.jpg&u=20240423183955)

![[Graphic News] 77% of young Koreans still financially dependent](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/22/20240422050762_0.gif&u=)

![[Pressure points] Leggings in public: Fashion statement or social faux pas?](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050669_0.jpg&u=)