Labor laws hurt start-ups

Foreigner quotas, visa rules provoke firms to seek loopholes

By Korea HeraldPublished : June 4, 2015 - 20:23

This is the third article in a series on foreigners working in Korea’s technology start-up ecosystem. Sang Youn-joo and Stephanie McDonald contributed to this report. ― Ed.

Etienne Maurin hadn’t finished graduate school when Kim Min-kee sought to found a start-up with him.

A whiz at programming languages like Ruby, the master’s student from France was the most trustworthy partner to help Kim develop My Memoirs, a story-sharing platform inspired by his time working with cancer patients who wanted to reminisce in their last days.

But research and consulting did not prepare Kim for the headache that hiring a foreigner entailed.

“We tried everything, all the different processes, but (the application) was denied every time,” he said. Between multiple calls to immigration and getting slammed with new requirements when visiting the office, it took around four months to secure Maurin’s work visa.

Kim believes that he would probably get a different response from each different immigration agent at any given time.

Etienne Maurin hadn’t finished graduate school when Kim Min-kee sought to found a start-up with him.

A whiz at programming languages like Ruby, the master’s student from France was the most trustworthy partner to help Kim develop My Memoirs, a story-sharing platform inspired by his time working with cancer patients who wanted to reminisce in their last days.

But research and consulting did not prepare Kim for the headache that hiring a foreigner entailed.

“We tried everything, all the different processes, but (the application) was denied every time,” he said. Between multiple calls to immigration and getting slammed with new requirements when visiting the office, it took around four months to secure Maurin’s work visa.

Kim believes that he would probably get a different response from each different immigration agent at any given time.

“It’s very subjective, but the people (at the immigration office) don’t actually know. … It makes the process even more frustrating.”

Grievances with immigration are nothing new to foreigners in Korea and their employers, especially in new businesses. But the constantly changing rules reflect a time of upheaval, as demands for diversity and labor deregulation outpace the infrastructure to handle them.

Apart from logistical nightmares, restrictive visa and hiring laws are hindering small companies in their early stages, when they need the most hiring flexibility, entrepreneurs like Kim pointed out.

“(As an early-stage start-up), you don’t have the funding, so it’s really important to find people with the same vision, because they will take less pay to make something happen,” Kim said. “If you can’t get a visa for them, then it’s even harder.”

Many in the tech industry complain that laws are too vague and hard to even learn about. Entrepreneurs say restrictions lead some small companies to seek loopholes or illegal alternatives.

David-Pierre Jalicon, chairman of the French-Korean Chamber of Commerce and Industry, said the current system was very complicated with too many regulations subject to interpretation.

“I came a long time ago to Korea. I had a vision of Korea as an easy country. Now I see Korea as a complicated country where for everything you need a lawyer,” he said. “The system looks unbalanced. And we don’t see what could be a counterbalance for reassuring potential foreign start-ups to join the system.”

Capital and quotas

The visa is the No. 1 problem for foreigners in tech start-ups, said Choi Hong-seok, assistant manager of the Seoul Global Center, a foreign resident assistance agency run by Seoul City.

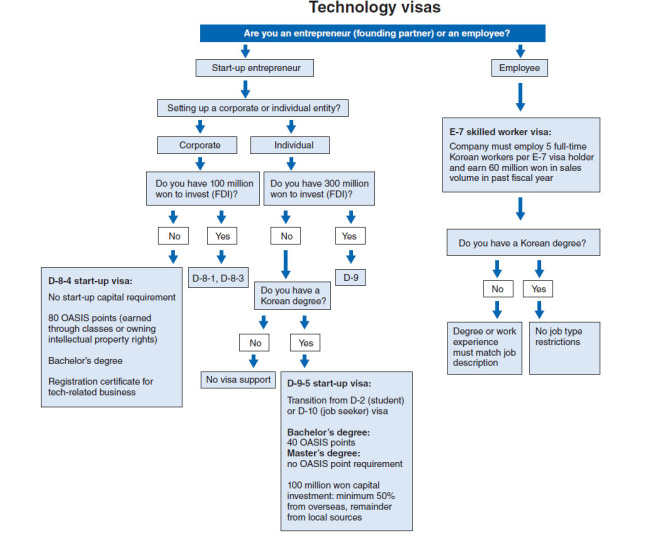

Two regulations form the biggest legal stumbling blocks for small multicultural businesses in Korea: Foreign entrepreneurs have struggled with the high investment requirements to found their companies, while all companies ― regardless of size or founders’ nationality ― must hire five full-time Korean employees for every E-7 visa holder.

The E-7 visa, which was issued to over 18,000 employees last year, is allotted to 83 types of high-skilled workers, covering technology development and other areas such as marketing and design. Applicants must prove with experience or education that their talent is unique and cannot be done by a Korean.

For tech companies aiming overseas, the implications of these regulations are amplified as local minds might not have the necessary global experience, entrepreneurs point out.

Several countries, such as France, cap the number of visas issued in the country, rather than per company, noted Jalicon of the FKCCI.

He stressed that companies must hire the like-minded people they need especially in their early stages, which may mean partners share the same background such as education or culture. Other entrepreneurs pointed out the difficulties and high search costs of securing new partners out of strangers to be invested as part of the team.

“When the company has more than two or three employees, for sure they will hire Korean people. So on a long-term basis, everybody is a winner,” Jalicon said.

He added that legal restrictions were vague and unpredictable, which might make foreign investors wary of the local business environment.

“There is discrimination, clearly. It’s discriminant and inconsistent,” he said. “There should be no different treatment from foreigner to Korean.”

The issue is exacerbated as more entrepreneurs want to enter the industry.

Choi of the Seoul Global Center noted that new businesses housed at the Seoul City-run agency’s incubation centers have been shifting from manufacturing and service sectors toward tech since 2010.

For nonpermanent residents unconnected to Korea by familial or blood relations, the cost to obtain an investment visa is 100 million won ($90,000) for corporate investments and 300 million won for a sole proprietorship. Entrepreneurs without deep pockets struggle to get funding before incorporating, leaving them in a catch-22.

Due to the difficulties of setting up in Korea, foreign entrepreneurs doing business here often seem to be incorporated abroad, noted Alexander Bezzubov, an organizer of the Seoul Tech Society.

Meanwhile, as Korean universities boost their support for foreign exchange student programs, more and more young qualified international professionals study here and learn Korean, only to find limited employment options when they graduate.

Most end up returning home, unable to find a job here due to limited information on top of labor restrictions, according to Simon Chan, co-founder of local job hunting website JobSeekr and a master’s student at Seoul National University.

“They’d probably want to stay in Korea but … there’s just minimal opportunity for them to find a position to stay in Korea,” said Chan.

According to a 2013 survey by the Small and Medium Business Administration of foreign students and researchers at Korean universities and institutes, over 48 percent said they would like to establish a tech start-up here.

Hongik University master’s degree alumnus Daghan Kirisci, a 3-D designer for video-making platform Vivio, said most of his peers returned home while some found jobs as teachers or in large companies, but he doesn’t know any like him who went into a start-up. “I believe some companies find the foreign visa process very difficult as they have to give a legitimate reason for hiring a foreigner (rather) than a Korean,” he added.

Those who cannot join the system sometimes try to beat it. Entrepreneurs who cannot afford the investment frequently end up setting up their company by moonlighting on a job hunting or tourist visa.

Because of a mismatch in the regulations, Choi of the Seoul Global Center added, some foreigners get stuck in a gray area wherein they can set up their company but can’t afford the visa to pay themselves.

“According to our commercial law, it is illegal, but according to immigration law, if the person gets a salary, it is not illegal. So that’s why it is illegal, but on the other hand it is not illegal. Complicated,” Choi said.

Several start-up entrepreneurs who asked not to be named, some of whom had studied at Korean universities, said they found bigger companies to sponsor their visas so they could work on their start-ups.

“When you’re doing your own project, it’s difficult (to give up on it),” said one start-up entrepreneur who graduated in Korea and found a larger company sponsor. “Other foreigners here, they’re just English teachers. They don’t have any kind of special education. If you come in with (specialized) education to do something you want, it’s very complicated.”

Kim of My Memoirs has seen some businesses employing foreign employees under other people’s names and funneling the salary indirectly, especially for short-term work. It is a practice that is seen across industries in Korea beyond the tech sector.

“This pertains to a lot of localization projects like translating into Indonesian or Vietnamese,” Kim explained. “A lot of these people don’t have the E-7 visa. They have a temporary working visa, and they can’t contract them legally, so they hire a friend or organization and then they pay them in cash.”

Kim sees it as a small but growing issue with little oversight.

“I think it’s getting bigger and bigger, especially with a lot of companies trying to localize and go global,” he said. “And I think there’s still too much gray area when it comes to these things. Employers … get away with it, and they just get a slap on the wrist if they get caught.”

Kim, also a co-organizer of English-language meetup group Entrepreneurs in Seoul, suggests that since start-ups are so sensitive to early-stage hiring, their employees should be allowed a special visa that allows them to legally earn an income while processing their paperwork.

Government solutions

Jason Lee, a U.S. citizen raised in Korea, didn’t realize how hard it would be to set up a company as a foreigner. Student and work visas were always handled for him. But as an entrepreneur with limited funds, he had to make three or four tourist visa runs to Japan in the first year of establishing J.J. Lee Company, a social networking platform developer.

“It was so stressful and I thought I would have to go back to the U.S.,” he said, even though he had no friends or life there.

After he pestered various government agencies, the Ministry of Justice offered him a new solution: the D-8-4 technology start-up visa, which required a bachelor’s degree and ownership of intellectual property, and no capital investment requirement. Fortunately for the Yonsei University graduate, he already held two software patents, and acquired the first D-8-4 visa.

He said he felt fortunate to qualify for the visa, but told immigration officials that the patent ownership requisite was not rational and would be nearly impossible for a foreigner with no Korean background ― it took him over two years to obtain his first patent, which was completely separate from his current business idea.

“I kept telling them, ‘If you want to see other foreigners doing business in Korea, you have to get rid of this requirement,’” he said.

Recognizing Lee’s and others’ concerns, officials last year created a series of business classes for foreign entrepreneurs to earn points toward the visa under the Overall Assistance for Startup Immigration System program, run by multiple government agencies. OASIS completed its first full session last month, making over a dozen students eligible for the tech start-up visa.

JobSeekr co-founder Chan, a British entrepreneur, said if it weren’t for the D-8-4 visa, his business partner Andrej Belcijan would probably not have been able to work, and the company would not have been able to continue.

He suggested that skilled foreign developers who graduate from Korean universities should be given an easier time to get hired.

“I think it’d be nice if we got to the stage in the future if tech could lead the kind of charge where nationality isn’t as important. It could be one of the first industries to break through,” he said.

The SMBA is considering expanding its support for foreigners to nontech enterprises, too, but the state agency has a lack of experience with foreigner issues, according to Choi of the Seoul Global Center, which works closely with the SMBA on the OASIS program. He said immigration officials are deregulating slowly due to high traffic and demand.

Lee, however, suggested that the government seems to be acting with caution over how the public will react to increased support for foreigners, including offering them business grants funded by taxpayers.

Lee realizes that as the first D-8-4 holder and a recipient of one such grant for 350 million won, he is expected to set a good example and have a positive impact on the local perception.

“They’re carefully starting this kind of support program really slowly and quietly, and they will try to release some success cases,” he said. “But right now, even I’m scared of this. It’s going to be a huge issue.”

The Ministry of Justice has also established the D-9-5 visa for Korean degree holders who establish companies with individual ownership. Tailored to Chinese students who face foreign direct investment remittance restrictions, the new law lowers the requirement from 300 million won to 100 million won, half of which can consist of local funds, Choi of the Seoul Global Center explained.

Jalicon also pointed out that the government has been working to relax the foreign worker quota in recent months.

On May 6, the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy announced several deregulation measures for foreign-invested companies, including lifting the quota for new “small” foreign-invested companies for the first two years of their establishment, starting this month. The quota had already been a relaxed 50-70 percent ratio of foreign to local employees for foreign-invested companies, according to the Ministry of Justice. MOTIE told The Korea Herald that the company size requirement and exact date of the new deregulation’s kickoff had not yet been finalized.

Additionally, the Ministry of Justice said that while the quota was put in place to protect jobs for the youth, it would continue to ease the hiring quota for high-skilled foreign workers who possess skills that cannot be replaced with local talent.

Further, this year the Justice Ministry eased the E-7 visa requirements for Korean degree holders, who now can take any job regardless of degree or previous experience.

Jalicon praised MOTIE’s new policy on the foreign worker hiring quota, which he had been urging for several years.

“All those were specific requests of the FKCCI and we sincerely appreciate the efforts of the government. We believe in practical measures, so when something is good and a step forward, it should be mentioned,” he said.

Visit the Korea Immigration Service at immigration.go.kr for official visa requirements and the Korea Trade-Investment Promotion Agency at investkorea.org for foreign investment guidance. For consultations and more information on the OASIS program, contact Seoul Global Center at sgcbiz1@gmail.com.

By Elaine Ramirez (elaine@heraldcorp.com)

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[Herald Interview] 'Amid aging population, Korea to invite more young professionals from overseas'](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/24/20240424050844_0.jpg&u=20240424200058)

![[KH Explains] Korean shipbuilding stocks rally: Real growth or bubble?](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/25/20240425050656_0.jpg&u=)