Looking in from the outside, it is difficult to pinpoint how exactly Nepal can recover from this most recent catastrophic earthquake. The area within the Ring Road may seem relatively unaffected, but communities like Chandeshwori, Tokha, just below the Shivapuri National Park, and villages surrounding Banepa and Nagarkot, to name just a few, have been severely hit. Homes have been destroyed, people have been buried under rubble and millions are camping out in the open under the rain for fear of ongoing aftershocks. As of the day this was written, some have still not received any aid.

It is not easy to comprehend for those in the Valley the enormity of entire villages being leveled, while most Kathmandu inhabitants have gotten away with cracks in our houses. Aside from those numerous brave ones who have headed to the outskirts to help and seen the wreckage firsthand, the most real signifier of our loss was the mind-boggling collapse of the Kasthamandap in the Basantapur Durbar Square, along with the spine-chilling damages borne by numerous other temple structures in and around the three durbar squares. Temple structures all across the Valley and in other earthquake-affected areas, including the Nuwakot and Gorkha Durbars and in Bandipur, have suffered severe damage.

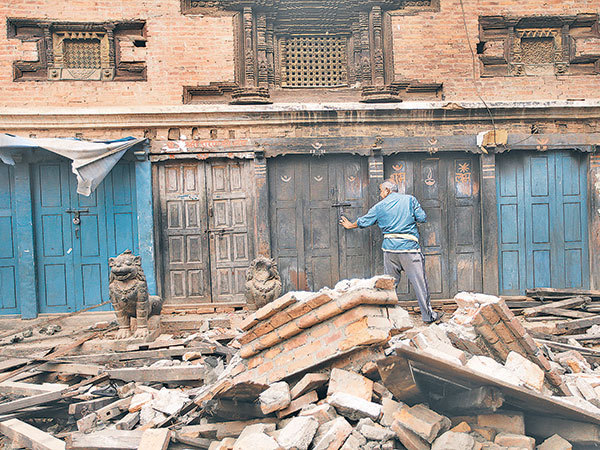

Images of the destruction of our heritage sites have moved the world, adding to the general emerging picture of Nepal’s being devastated by the 7.9 magnitude earthquake that came roaring (that’s what it sounded like to me) toward us on that Saturday morning one week ago. People in and outside the country are mourning the loss of lives, of personal and public property and of the centuries-old Newar architecture that is, in some ways, synonymous with our traditions.

It is not easy to comprehend for those in the Valley the enormity of entire villages being leveled, while most Kathmandu inhabitants have gotten away with cracks in our houses. Aside from those numerous brave ones who have headed to the outskirts to help and seen the wreckage firsthand, the most real signifier of our loss was the mind-boggling collapse of the Kasthamandap in the Basantapur Durbar Square, along with the spine-chilling damages borne by numerous other temple structures in and around the three durbar squares. Temple structures all across the Valley and in other earthquake-affected areas, including the Nuwakot and Gorkha Durbars and in Bandipur, have suffered severe damage.

Images of the destruction of our heritage sites have moved the world, adding to the general emerging picture of Nepal’s being devastated by the 7.9 magnitude earthquake that came roaring (that’s what it sounded like to me) toward us on that Saturday morning one week ago. People in and outside the country are mourning the loss of lives, of personal and public property and of the centuries-old Newar architecture that is, in some ways, synonymous with our traditions.

The despair that the Nepali people feel about the destruction of their heritage sites is a deep one. The durbar squares are not just emblems of our culture, and a commemoration of the immense skills of the Newar artisans who worked wood, stone, metal, and clay to build these structures. They are also living heritage sites that embody the ongoing practices and rituals of the Newar people, who live and worship in and around the durbar squares, whose temples house age-old deities that are specific to the communities that reside there.

Most people assume that the destruction of monuments means the destruction of a culture. That is not correct. Rohit Ranjitkar, a conservation architect and Lalitpur resident, is the country director of the Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust ― a not-for-profit organization, based in Lalitpur; it has been on the ground since 1991, working to restore and conserve these monuments. Ranjitkar points out that earthquakes occurred here before, wreaking havoc in the durbar squares; yet century after century, the communities and residents of these former city states have stoically set about rebuilding them, never abandoning their religious sites despite the destruction wrought upon them by forces of nature. Ranjit himself is passionate about architecture; yet, with a great deal of common sense and an unerring practicality, he says that it is really us, the aesthetes, who care more about the architecture. To the people of Lalitpur, it is but a beautiful shell that houses the more important deities, which hallow the sites of the rituals.

Yet, the necessity to rebuild is obvious. While the fabric of society may not be immediately torn apart by the collapse of the monuments, the communities that rely on these communal structures for moral and physical support ― for example, the Manga Hiti fountain is a reliable source of water for Lalitpur residents ― will fall apart without the existence of the actual physical place; a case in point is the Rajupadhayas, who, for generations, have been the pujaris of the Taleju Temple that is at the corner of Mul Chowk in the Lalitpur palace complex. The top of the temple has been damaged, but the priests plan to continue the rituals that surround the deity, by transposing the deity into their own homes if necessary. The question is, how long can that continue without some real loss of ritual?

Here is the tricky part: in times of disasters such as these, say both Ranjit and Neils Gutschow, a German architect who has worked on and researched Newar architecture in Nepal since 1971, that while people may be clued in on how to give for humanitarian purposes, either to large organizations such as the Red Cross who are typically first responders, or to different grassroots organizations, there are no such mechanisms established, at least in Nepal, for people who want to give to the conservation and preservation of monuments.

The KVPT has been on the ground in Lalitpur Durbar Square since Saturday, extracting people out of the piles of rubble, with the help of well-established and extremely strong community groups, identifying the valuable artifacts that can be saved, inventorying them, and then locking them safely in the Patan Museum.

Without their vigilance, which due to lack of manpower, cannot extend for the moment outside of Lalitpur, many of the fallen, priceless pieces might have been left to the elements, and worse still, to the people who would smuggle them out to be sold. It was only on Day 4 (if you consider Saturday as Day 1) that the army came in to sift through the debris and help support what had already become a strong grassroots, community-based conservation effort.

In this piece I have used Lalitpur, and particularly the Durbar Square in it, as a case study. Unfortunately, not all the heritage sites have been as lucky. Kathmandu Durbar Square has had very few people rallying around it, and Bhaktapur, while having a strong community, has suffered regardless ― both its old residential buildings and its religious sites have been severely damaged.

If there is a lesson to be learnt from this calamity, it is this: we will rebuild. Our heritage sites are a very clear indicator of resilience, with temples rising out of the ruins of old ones. The real question here is, when we rebuild, how should we go about it?

How we rebuild our temples to be resilient, with new foundations, as Rohit Ranjitkar knows to be necessary, could be a metaphor for how we rebuild our nation, paying attention to our roots and our heritage, but recasting and forging something stronger and newer. If this should sound shamelessly superficial, look around you: do we ever want to go through this again? We may not be able to control nature, but we can certainly control how we build our future.

By Sophia Pande

(The Kathmandu Post)

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[Graphic News] More Koreans say they plan long-distance trips this year](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/17/20240417050828_0.gif&u=)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240419100350)

![[From the Scene] Monks, Buddhists hail return of remains of Buddhas](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050617_0.jpg&u=20240419175937)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240419100350)

![[Today’s K-pop] Illit drops debut single remix](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050612_0.jpg&u=)