A sparkle from Bohemia

Exquisite glassworks from Czech Republic on exhibit at National Museum of Korea

By Korea HeraldPublished : Feb. 17, 2015 - 16:38

From the classic Queen song “Bohemian Rhapsody” to the boho-chic fashion statement, references to the Czech region of Bohemia have been thrown around in a variety of different contexts throughout modern culture.

However, it is a relatively lesser known fact that the area has for centuries been celebrated for its intricate, high-quality glass craftsmanship. Even Swarovski, the internationally renowned crystal glass brand, was founded by a man from the northern parts of Bohemia.

An exhibition that opened this week at the National Museum of Korea is a rare opportunity to view the development of the Bohemian glass art from antiquity up to modern times.

Titled “The Story of Bohemian Glass,” the show features a collection of some 340 awe-inspiring items on loan from Prague National Museum and Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague.

“It is the first time the two esteemed Prague-based museums are collaborating on a display this large,” said Park Hye-won, curator of the National Museum of Korea during a press preview Monday.

Upon entry, visitors are met with an array of sparkling ornaments in a dimly lit gallery.

However, it is a relatively lesser known fact that the area has for centuries been celebrated for its intricate, high-quality glass craftsmanship. Even Swarovski, the internationally renowned crystal glass brand, was founded by a man from the northern parts of Bohemia.

An exhibition that opened this week at the National Museum of Korea is a rare opportunity to view the development of the Bohemian glass art from antiquity up to modern times.

Titled “The Story of Bohemian Glass,” the show features a collection of some 340 awe-inspiring items on loan from Prague National Museum and Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague.

“It is the first time the two esteemed Prague-based museums are collaborating on a display this large,” said Park Hye-won, curator of the National Museum of Korea during a press preview Monday.

Upon entry, visitors are met with an array of sparkling ornaments in a dimly lit gallery.

It may be difficult to believe that the milky ceramic teapots, onyx vases gilded with gold, and lotus-shaped turquoise plates are all made of glass, and not of rare stones.

Like Korea, the Czech Republic has a tumultuous history of invasion and occupation.

Prague flourished in the 16th century as the center of Renaissance art, but growth was soon stunted due to war. After a period of oppressive monarchy, the Czech were overtaken by Nazi Germany and then later by communists backed by the Soviet Union. Democracy was restored only in 1989.

The history of how the Czech people struggled to preserve traditions and culture amidst turmoil can be traced through their shimmering moldings.

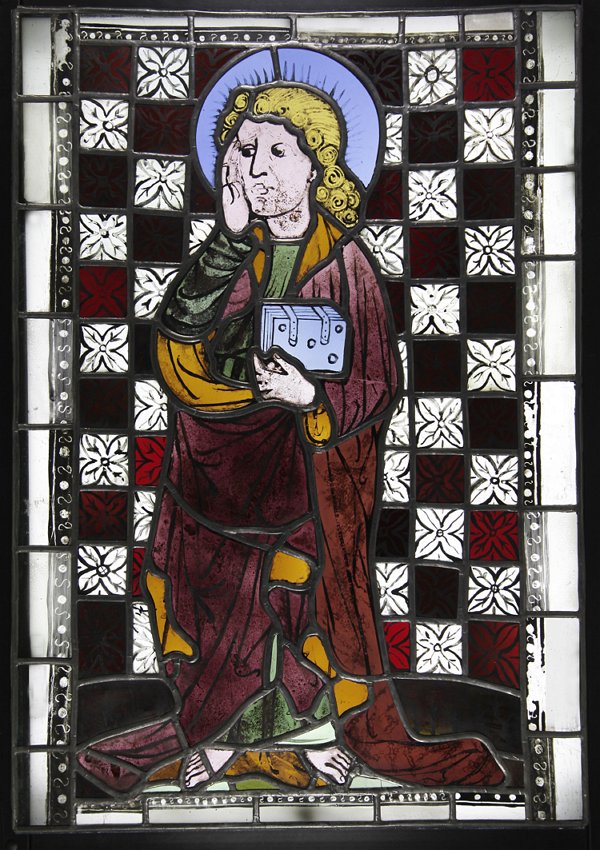

“One significant development is the fusion of Christianity and glasswork,” Park commented. “Because churches at the time were banned from accumulating wealth, glass was an affordable way to fabricate religious adornments without sacrificing luster.”

Czech glass artisanship fully blossomed in the Baroque period. Symbolic pieces include the “Flacon” made with ruby-glass and the “Covered Goblet with a Wild Boar and Deer Hunting Scene” from the 1720s, fabricated using double-ply walled glass vessels.

“This intricate technique entails the overlapping of two very thin layers of glass, between which detailed silver decorations are inserted,” Park explained. “Every hair of fur on the hunting dogs, every leaf of the trees is visible on this finely crafted cup.”

The turn of the 20th century brought forth innovative designs and techniques in Bohemian glasswork, combined with the then trending Art Nouveau style. With abstract patterns, geometric structures, and vivid coloring, glass came to be regarded not as a substitute for precious stones but as a valuable medium for artistic creation in itself.

“Even when most art forms were suppressed, glasswork, seen as a relatively non-political aesthetic area, was able to avoid strong restriction,” Park said. Glass was thus able act as one of the sole means for Czechs to express themselves freely under a totalitarian regime.

One important item of the era is the “Vase” made at the Loetz glass factory. An iridescent shade of purple, silver, and green, this fluid-shaped vase embodies some of the more experimental techniques artists began to employ in forging glass.

Other striking pieces include “Object” ― a lens-shaped installation that redirects light and reconstructs the surroundings of the beholder ― by Vaclav Cigler, and “Wave” by Pavel Hlava, with delicate strands of gold spun into a wing-shaped glass wedge.

Bohemian glass is forged with skill and tenacity, achieving at once high durability and exceptional transparency. Like the history of its people, the structures are resilient yet ever-evolving.

“Today, artists continue to push the boundaries of glasswork through creativity, technique, and government-backed education systems,” Park said.

“The Story of Bohemian Glass” continues at the National Museum of Korea until April 26. Admission is free.

By Rumy Doo (bigbird@heraldcorp.com)

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[AtoZ into Korean mind] Humor in Korea: Navigating the line between what's funny and not](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/22/20240422050642_0.jpg&u=)

![[Exclusive] Korean military set to ban iPhones over 'security' concerns](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050599_0.jpg&u=20240423183955)

![[Herald Interview] Why Toss invited hackers to penetrate its system](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/22/20240422050569_0.jpg&u=20240422150649)

![[Graphic News] 77% of young Koreans still financially dependent](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/22/20240422050762_0.gif&u=)

![[Exclusive] Korean military to ban iPhones over security issues](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050599_0.jpg&u=20240423183955)

![[Today’s K-pop] Ateez confirms US tour details](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050700_0.jpg&u=)