What was the upshot of my year in reading ― the ideas, the through lines that most stirred or provoked me in 2014? The dominant thread was what we might call that of common experience, work that finds significance in incidental things.

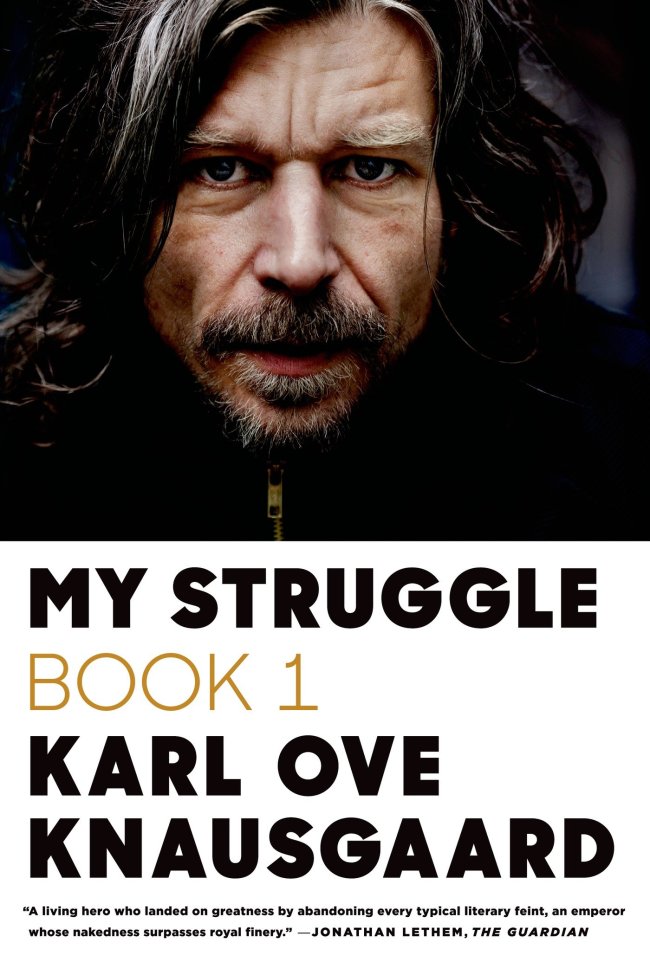

Karl Ove Knausgaard has become the poster child for this sort of work; his six-volume autobiographical opus “My Struggle” is all about a deep dive into the mundane. “Over recent years,” he writes toward the end of the second volume, “I had increasingly lost faith in literature. ... The only genres I saw value in, which still conferred meaning, were diaries and essays, the type of literature that did not deal with narrative, that were not about anything, but just consisted of a voice, the voice of your own personality, a life, a face, a gaze you could meet.”

Karl Ove Knausgaard has become the poster child for this sort of work; his six-volume autobiographical opus “My Struggle” is all about a deep dive into the mundane. “Over recent years,” he writes toward the end of the second volume, “I had increasingly lost faith in literature. ... The only genres I saw value in, which still conferred meaning, were diaries and essays, the type of literature that did not deal with narrative, that were not about anything, but just consisted of a voice, the voice of your own personality, a life, a face, a gaze you could meet.”

Knausgaard’s project ― Volume 3 came out in June ― seems to signal something vivid about what books and art can do. His purpose is to slow down and use language to reframe the details of a life.

He spends 60 pages describing a 4-year-old’s birthday party, half a book on preparations for a funeral. It should be boring, but it is exhilarating instead. Why? Because by zeroing in on activities we rarely read about ― “the parts people skip,” in Elmore Leonard’s pointed phrase ― Knausgaard brings us face to face with not just his daily struggles but also our own.

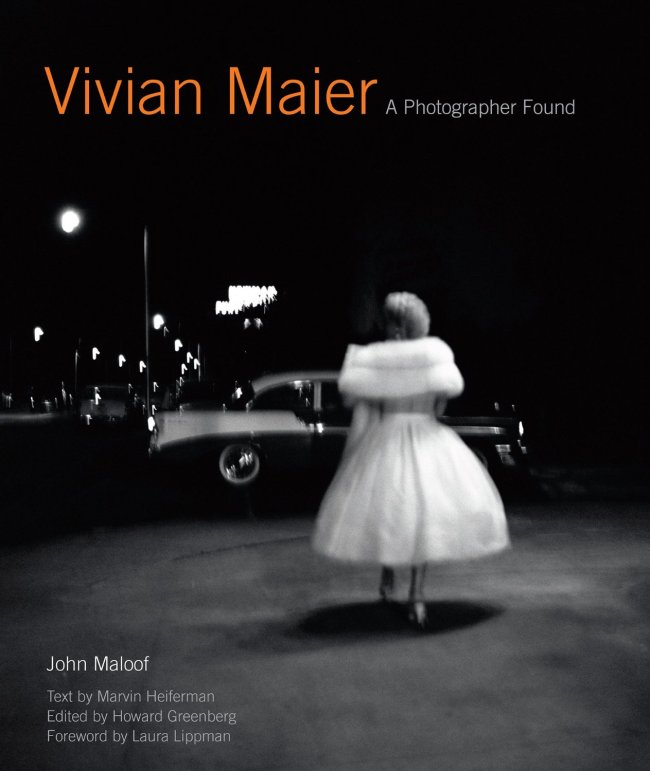

This aesthetic is not dissimilar to that of Vivian Maier, the Chicago- and New York-based street photographer whose work was widely distributed and appreciated only after her death in 2009. In the art book “Vivian Maier: A Photographer Found,” put together this year by John Maloof, we find nearly 250 images that present a visual analogue to Knausgaard’s literary project: the epic of the everyday.

What makes such a notion compelling is that it continually turns our attention to the sorts of moments we all share. In her graphic novel “Lena Finkle’s Magic Barrel,” for instance, Anya Ulinich tells the story of a thirtysomething mother of two in Brooklyn, struggling with her romantic life, her career, her sense of worth. That this does not make her any different from the rest of us is the point precisely, allowing Ulinich to frame her protagonist’s story as an engine of empathy.

The same is true of Dinah Lenney‘s essay collection “The Object Parade,” which employs common household objects ― a table, a piano, a watch ― as the starting points for a series of loosely connected family stories in which memory and emotion, and the interplay between them, fill the function of the narrative arc.

The avatar of this sort of writing is, of course, Alice Munro, the 2013 Nobel laureate whose “Family Furnishings: Selected Stories, 1995-2014” was published in the fall. The two dozen pieces in the book remind us that meaning emerges from reflection as much as (or more than) drama. Her characters wrestle with obligation, faithlessness (their own and others’); their lives are less small than, like so many of ours, constrained.

Such a point of view also marks “Suspended Sentences,” a collection of three novellas by this year’s laureate Patrick Modiano ― in which, like the work of Knausgaard or Munro, little happens and yet somehow everything does.

For Modiano, the world is a construct of memory rather than of mortar, which means that, as the world changes around us, essential pieces of ourselves are stripped away. It’s a sensation we all have had at some point or another, walking the streets of a neighborhood in which we used to live. Again, the point is to stop, to look and listen, to take stock of who and where we are.

This, I would suggest, is the most essential connection literature has to offer: not narrative so much as nuance, in which the smallest details add up to something larger than themselves.

By David L. Ulin

(Los Angeles Times)

(Tribune Content Agency)

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[KH Explains] How should Korea adjust its trade defenses against Chinese EVs?](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/15/20240415050562_0.jpg&u=20240415144419)

![[Today’s K-pop] Stray Kids to return soon: report](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/16/20240416050713_0.jpg&u=)