[Herald Interview] Bringing Joseon treasure to light

Confucian printing woodblocks a great resource for modern Koreans, scholar says

By Claire LeePublished : Dec. 17, 2014 - 21:07

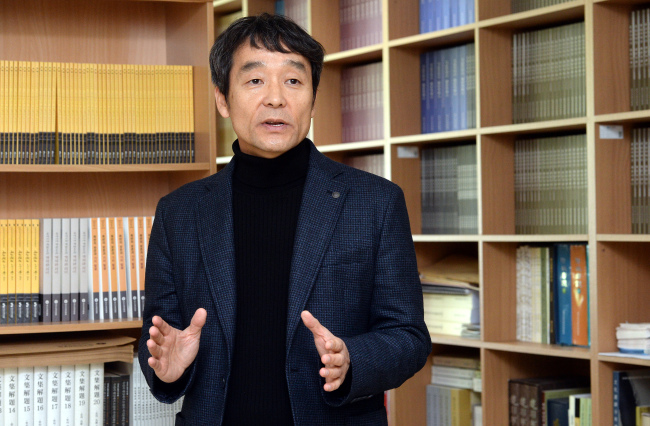

ANDONG, North Gyeongsang Province ― Scholar Lim No-jig was born in Andong, home to hundreds of “jongga” ― the prestigious households descended from distinguished Joseon-era scholars through the eldest son of each generation.

“Although I wasn’t a member of a jongga family, I certainly benefited from the region’s rich culture, which is heavily influenced by Joseon’s Confucianism and ethics,” Lim said during an interview with The Korea Herald in his hometown.

The scholar heads the Woodblock Research Center, a unit of the Advanced Center for Korean Studies in Andong. The center specializes in studying thousands of Joseon woodblocks from the region ― mostly produced and used to print scholarly writing and poetry by Confucian scholars.

“Although I wasn’t a member of a jongga family, I certainly benefited from the region’s rich culture, which is heavily influenced by Joseon’s Confucianism and ethics,” Lim said during an interview with The Korea Herald in his hometown.

The scholar heads the Woodblock Research Center, a unit of the Advanced Center for Korean Studies in Andong. The center specializes in studying thousands of Joseon woodblocks from the region ― mostly produced and used to print scholarly writing and poetry by Confucian scholars.

Lim is considered a pioneer of Joseon woodblock studies, as he initiated a project in 2002 to collect printing blocks that had mostly been in possession of individuals and families.

Among Lim’s collection are writings by Yi I and Yi Hwang, two of the most prominent Korean Confucian scholars of the Joseon Dynasty.

Although there are more than 60,000 panels housed at Jangpangak, a special storage facility of the Woodblock Research Center, Lim had to start from scratch.

It required him to visit each jongga and persuade the heads of the families, many of whom thought it was disrespectful to their ancestors to store their relics outside their homes.

He told them the blocks would be completely safe at his institute, and it would be more meaningful for the relics to be studied so the public can learn about them better.

“Many found the idea difficult,” Lim said. “Some thought of it as selling their souls.”

While many family members knew the blocks were important, some were not aware of their historical value. A number of them had their family relics stolen, while not fully understanding what the blocks really were or represented.

One time, a head member of a jongga had his blocks stolen from storage just a day before Lim’s scheduled visit to collect them for storage at the research institute.

“As a researcher, such theft cases really disheartened me because sometimes the family members couldn’t even tell which of the relics were stolen,” Lim said.

But there were lucky occasions as well. For instance, at a jongga house, a “hanok,” he accidentally came across a woodblock being used as the raised wooden floor of the house’s shrine.

What he found was a map of the Korean Peninsula, China and Japan which was carved onto the wooden panel during the Joseon Dynasty.

“I was actually there to collect some ancient texts,” he said.

“And as I was leaving the shrine, it felt as if something was tugging behind my back. I turned back and touched the underside of the raised wooden floor. I could feel the carved letters with my hands.”

The writings carved on the blocks include poems, scholarly writings on Confucian thought, and letters scholars wrote to each other. Letters, in particular, were a great way for Joseon scholars to discuss their academic interests and opinions with each other at a time when transportation was limited.

Joseon poetry, on the other hand, offers a rare glimpse into the lifestyle of Joseon scholars, who valued scholarship, appreciated nature and loved to write.

“It’s not common for today’s scholars to write poems,” he said. “But Joseon scholars wrote poems almost every day. They would write poems at the same frequency at which they ate.”

Lim said the texts carved on the blocks, which have been recommended by the Korean government for inclusion on UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register, can be a great resource in many ways for today’s Koreans.

“One of the things that makes it hard for us to promote the importance of these blocks is that the texts are in Chinese characters, and Koreans no longer read Chinese every day,” Lim said.

“But these writings really tell us where we should be heading as Koreans. They are our history and our reference books. They tell us what to do as well as what not to do. That is why I think it is important to translate the texts into modern-day Korean and make them more accessible to the public.”

By Claire Lee (dyc@heraldcorp.com)

![[AtoZ into Korean mind] Humor in Korea: Navigating the line between what's funny and not](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/22/20240422050642_0.jpg&u=)

![[Exclusive] Korean military set to ban iPhones over 'security' concerns](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050599_0.jpg&u=20240423183955)

![[Graphic News] 77% of young Koreans still financially dependent](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/22/20240422050762_0.gif&u=)

![[Herald Interview] Why Toss invited hackers to penetrate its system](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/22/20240422050569_0.jpg&u=20240422150649)

![[Exclusive] Korean military to ban iPhones over security issues](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050599_0.jpg&u=20240423183955)

![[Today’s K-pop] Ateez confirms US tour details](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050700_0.jpg&u=)