During five weeks of living in the Korean community near Flushing area of New York City, I often wondered why the Korean residents gave up their life in Korea for a new life in the U.S. Many of the Koreans work long hours running small businesses. New York City is a wonderland for tourists, but for residents it is an expensive, crowded place just like Seoul.

Over time, I began to ask Koreans what brought them to the U.S., and the answer was surprising similar: education. When I asked what was so attractive about U.S. education, most responded by saying that they came to the U.S. so that their children could learn English from an early age rather than because of the quality of the education itself. Most also added that children prefer the U.S. because school is less demanding and more fun.

to the U.S. so that their children could learn English from an early age rather than because of the quality of the education itself. Most also added that children prefer the U.S. because school is less demanding and more fun.

Migration, one of the oldest forms of human activity, takes to two major forms: push and pull. “Push migration” happens when people want to flee their homeland, usually because of war and political oppression. Some of the immigrants during the first wave of Korean immigration to the U.S. from the mid-1960s to the mid-1980s left to escape military dictatorship at home.

“Pull migration,” by contrast, occurs when people leave for a better material life in a new place. This was also a strong motivation during the first wave of Korean immigration. It is also the prime motive for many foreigners from poor countries who come to Korea for a better material life.

Creating an environment for children to learn English from an early age thus appears to be the prime mover in most recent immigration to the U.S. In the long sweep of migration past and present, this is unique because foreign language learning has rarely been a major pull for migrants.

At times in history, ruling elites have sent their children abroad for language learning or to boarding schools. An interesting example of this is Kim Jong-un, the current ruler of North Korea, who attended an elite boarding school in Switzerland. The experience abroad and language learning help give the elite social capital that it can use back home. Parents remain at home and return is always assumed.

The pull of language learning started in the 1990s as women took their young children to English-speaking countries to learn English while the men, who became known as “goose fathers,” remained in Korea to earn money. The trend has since weakened, but it established the idea that learning English from a young age was worth financial sacrifices and family separation.

Taken as a whole, the trend is disturbing because the costs are high and the benefits low. It joins the long list of mindless trends in Korea and elsewhere that potentially damage those who jump on board.

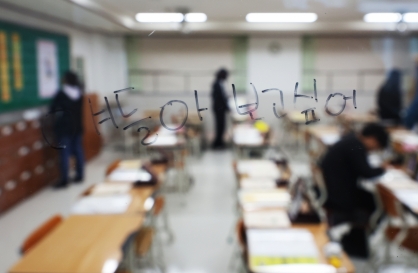

The most obvious problem is that learning English from an early age is not as important as the parents believe it is. Rightly or wrongly, Korean society uses English ability as a means of allowing entrance into the elite, mostly through test scores that control entrance to elite universities and powerful companies. Native-like fluency and pronunciation are not tested because the tests are not designed to test near-native proficiency. Many Koreans are able to get high scores without extended study in an English-speaking country.

Another problem is that the type of English required in professional situations requires mastery of content instead of native-like pronunciation. Professionals must know what they are talking about, not just how to talk. U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, for example has succeeded because of his mastery of content, managerial skills, and social capital (being a graduate of Seoul National University). His Korean accent has not held him back.

The biggest problem of all, of course, is that English immigration is about the parents and not their children. Most Koreans over the age of 45 are not proficient in English because they lacked opportunities to learn it well and find it difficult to learn in adulthood.

Like parents everywhere, they want to provide their children with an opportunity that they did not have, but it shifts their focus on what is good for their children. Immigrating to the U.S. may be good for the children, but immigration is essentially about cutting old ties and building new ones through sustained commitment. It is a serious decision that requires great care. Hopefully younger generations of Koreans who are more comfortable with English will look beyond English pronunciation to think about what is really good for their children.

By Robert J. Fouser

Robert J. Fouser, a former associate professor of Korean language education at Seoul National University, writes on Korea from Ann Arbor, Michigan. ― Ed.

Over time, I began to ask Koreans what brought them to the U.S., and the answer was surprising similar: education. When I asked what was so attractive about U.S. education, most responded by saying that they came

to the U.S. so that their children could learn English from an early age rather than because of the quality of the education itself. Most also added that children prefer the U.S. because school is less demanding and more fun.

to the U.S. so that their children could learn English from an early age rather than because of the quality of the education itself. Most also added that children prefer the U.S. because school is less demanding and more fun.Migration, one of the oldest forms of human activity, takes to two major forms: push and pull. “Push migration” happens when people want to flee their homeland, usually because of war and political oppression. Some of the immigrants during the first wave of Korean immigration to the U.S. from the mid-1960s to the mid-1980s left to escape military dictatorship at home.

“Pull migration,” by contrast, occurs when people leave for a better material life in a new place. This was also a strong motivation during the first wave of Korean immigration. It is also the prime motive for many foreigners from poor countries who come to Korea for a better material life.

Creating an environment for children to learn English from an early age thus appears to be the prime mover in most recent immigration to the U.S. In the long sweep of migration past and present, this is unique because foreign language learning has rarely been a major pull for migrants.

At times in history, ruling elites have sent their children abroad for language learning or to boarding schools. An interesting example of this is Kim Jong-un, the current ruler of North Korea, who attended an elite boarding school in Switzerland. The experience abroad and language learning help give the elite social capital that it can use back home. Parents remain at home and return is always assumed.

The pull of language learning started in the 1990s as women took their young children to English-speaking countries to learn English while the men, who became known as “goose fathers,” remained in Korea to earn money. The trend has since weakened, but it established the idea that learning English from a young age was worth financial sacrifices and family separation.

Taken as a whole, the trend is disturbing because the costs are high and the benefits low. It joins the long list of mindless trends in Korea and elsewhere that potentially damage those who jump on board.

The most obvious problem is that learning English from an early age is not as important as the parents believe it is. Rightly or wrongly, Korean society uses English ability as a means of allowing entrance into the elite, mostly through test scores that control entrance to elite universities and powerful companies. Native-like fluency and pronunciation are not tested because the tests are not designed to test near-native proficiency. Many Koreans are able to get high scores without extended study in an English-speaking country.

Another problem is that the type of English required in professional situations requires mastery of content instead of native-like pronunciation. Professionals must know what they are talking about, not just how to talk. U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon, for example has succeeded because of his mastery of content, managerial skills, and social capital (being a graduate of Seoul National University). His Korean accent has not held him back.

The biggest problem of all, of course, is that English immigration is about the parents and not their children. Most Koreans over the age of 45 are not proficient in English because they lacked opportunities to learn it well and find it difficult to learn in adulthood.

Like parents everywhere, they want to provide their children with an opportunity that they did not have, but it shifts their focus on what is good for their children. Immigrating to the U.S. may be good for the children, but immigration is essentially about cutting old ties and building new ones through sustained commitment. It is a serious decision that requires great care. Hopefully younger generations of Koreans who are more comfortable with English will look beyond English pronunciation to think about what is really good for their children.

By Robert J. Fouser

Robert J. Fouser, a former associate professor of Korean language education at Seoul National University, writes on Korea from Ann Arbor, Michigan. ― Ed.

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[KH Explains] How should Korea adjust its trade defenses against Chinese EVs?](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/15/20240415050562_0.jpg&u=20240415144419)

![[Today’s K-pop] Stray Kids to return soon: report](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/16/20240416050713_0.jpg&u=)