Lee faces tough task

New NIS chief tasked with cleaning house after Assembly approval

By Korea HeraldPublished : July 13, 2014 - 20:44

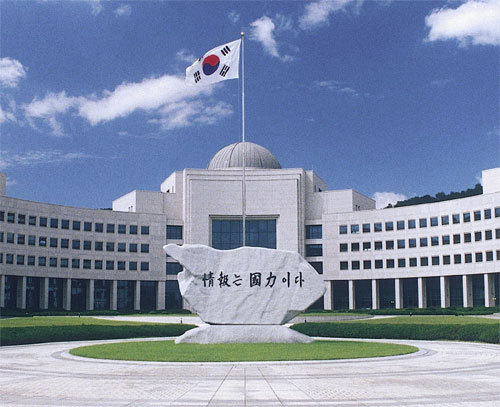

Lee Byung-kee has been cleared to take the helm of the National Intelligence Service, but he faces a difficult road ahead.

On Wednesday, the National Assembly gave Lee half-hearted approval, with opposition lawmakers adding that he was unfit to lead the spy agency as he is accused of incompetence and has been involved in political scandals.

After what critics describe as the NIS’ worst years since the end of the Cold War, the agency suffers from public distrust and low morale.

Intelligence officers have been implicated in an online smear campaign against liberal candidates in the 2012 presidential election. Although the courts have yet to decide whether the spies did in fact meddle with the poll, public distrust of the agency has increased since the allegations surfaced.

On Wednesday, the National Assembly gave Lee half-hearted approval, with opposition lawmakers adding that he was unfit to lead the spy agency as he is accused of incompetence and has been involved in political scandals.

After what critics describe as the NIS’ worst years since the end of the Cold War, the agency suffers from public distrust and low morale.

Intelligence officers have been implicated in an online smear campaign against liberal candidates in the 2012 presidential election. Although the courts have yet to decide whether the spies did in fact meddle with the poll, public distrust of the agency has increased since the allegations surfaced.

In addition, the NIS has been accused of a string of legal developments surrounding a North Korean defector who stood trial on charges of spying for Pyongyang.

In April, it was revealed that an NIS agent in China was directed to forge Chinese diplomatic papers in order to build a case against former Seoul City official Yoo Woo-seong. Yoo is accused of leaking the personal information of other North Koreans living in the South to Pyongyang agents.

The developments led to President Park Geun-hye dismissing deputy NIS chief Suh Cheon-ho. Nam Jae-joon, Lee’s predecessor, offered a rare public apology. Park declared she would overhaul the intelligence agency after the debacle.

But the incident also exposed the identities of “NIS black” agents in China. The agents’ identities are supposed to be unknown to Chinese authorities. Black agents help North Korean refugees get to Seoul.

As the opposition bloc pushes for sweeping reform of the spy agency, the conservatives say that the NIS needs to increase human intelligence in North Korea. A rising China and a revisionist Japan pose additional policy complications.

But some doubt Lee’s ability to change an NIS sandwiched between hardline conservatives and reform-minded liberals.

“Lee is a bureaucrat. I do not expect him to carry out any big reforms in the NIS,” Choi Young-jin, professor of Korean politics at Chung-Ang University said.

But expect Lee to play some role in Park’s North Korea policy, Choi added.

South Korean presidents traditionally pay more attention to their North Korea policies in their third year in office.

“Presidents usually take (North Korea policy) easy for the first few years. Then they start thinking, ‘will historians say I haven’t done enough?’” Choi said.

“I will erase all traces of the phrase ‘political intervention’ from my head,” Lee said when lawmakers grilled him about his controversial past during his nomination hearing last week.

Lee’s nomination last month sparked ferocious criticism from the opposition.

Lee was convicted of forwarding more than 500 million won ($490,000) in illicit political funds to another politician while serving as an adviser to Lee Hoi-chang, the conservative candidate in the 2002 presidential election. The newly appointed NIS chief was fined 10 million won for his role in the scandal.

“I have felt only heartfelt regret and sorrow for my role in the incident,” Lee said.

“I vow not to ever again involve myself in political issues if I am appointed to head the NIS.”

Opposition lawmakers were unconvinced.

“Would you, Mr. Lee, allow a former child molester become a teacher at a local primary school in your neighborhood?” Rep. Kim Kwang-jin said during the confirmation hearings.

“I think the same principle applies here.”

A former politician involved in illegal political funding cannot reform a corrupt spy agency, Kim said.

Legislators nevertheless confirmed Lee’s appointment, though also describing Lee as “unqualified” for the position in their report to the president.

Parliament does not have the legal authority to block Lee’s nomination. But experts say President Park would be under immense political pressure pushing ahead with Lee as her NIS chief if parliament opposes him.

But this doesn’t mean Lee lacks credentials.

The Seoul National University graduate is one of the few who have passed the annual state-sponsored Foreign Service exam, a test that have passing rates of less than one percent in some years. The former ambassador to Japan also served as an aide to presidents Roh Tae-woo and Kim Young-sam. He also worked as the second deputy chief in the forerunner of the NIS, the Agency for National Security Planning, in the late 1990s.

The supposed incompetence of the agency is another issue that Lee will have to address.

On July 7, an NIS agent was caught taking pictures of opposition Rep. Park Young-sun’s personal papers during Lee’s confirmation hearing at the National Assembly. The incident only added to the public’s distrust of the agency.

Rep. Park immediately expressed outrage when she confirmed the man was an NIS agent, yelling, “this is why nobody trusts our spy agency.”

Although it was later shown that the agent was in the Assembly legally, the situation highlighted the opposition’s claims of incompetence.

“Why is it that every time the NIS does something, like taking a simple picture, they get caught?” opposition Rep. Park Jie-won said once the commotion in the room died down.

Lee answered simply that he would do his best to address the situations facing the NIS.

South Korea’s state intelligence agencies have a history of getting involved in politics ― in the wrong way.

During the Syngman Rhee administration (1948-60), the Korea Research Bureau, a spy institution modeled on the U.S. Army’s Counter Intelligence Corps, was accused of being a political tool of the president by opposition lawmakers. Rhee was accused of using disguised thugs, often suspected to be KRB agents, to physically attack political opponents.

Under President Park Chung-hee (1961-79), the Korean Central Intelligence Agency kidnapped political opponents of Cheong Wa Dae, including the future president Kim Dae-jung.

A KCIA director eventually in 1979 assassinated Park, the current president’s father.

By Jeong Hunny (hj257@heraldcorp.com)

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[KH Explains] How should Korea adjust its trade defenses against Chinese EVs?](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/15/20240415050562_0.jpg&u=20240415144419)

![[Today’s K-pop] Stray Kids to return soon: report](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/16/20240416050713_0.jpg&u=)