The government is planning to craft a program for preliminary countermeasures by 2020, when Tokyo will host the Summer Olympics.

A sense of crisis about a shrinking society was expressed continuously during a meeting of the Council on Economic and Fiscal Policy’s committee on future options, which was inaugurated in January.

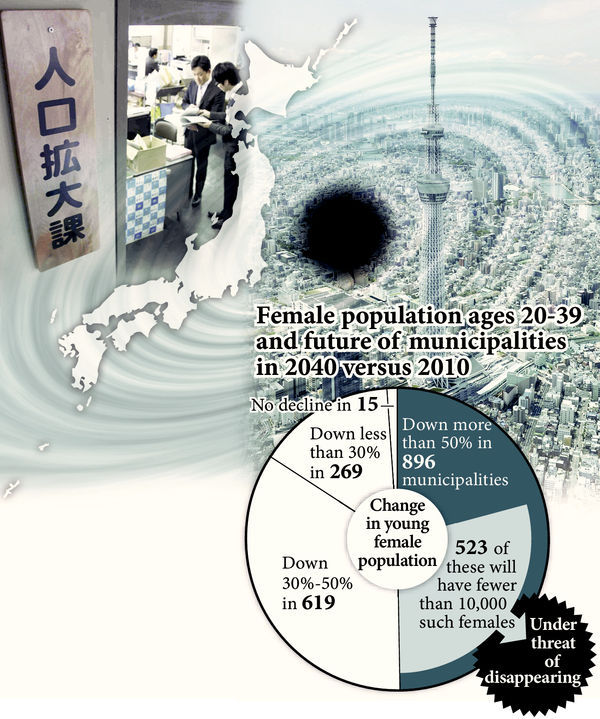

Hiroya Masuda, a former internal affairs minister, said: “More than 500 cities, towns and villages likely will disappear in 2040 and beyond. Can the future be changed by policy and resolve? Personally, I’m pessimistic about that.”

Fujiyo Ishiguro, president and CEO of strategic Internet professional services provider Netyear Group, said, “Given the prospect of the female population decreasing, I wonder if it is advisable to discuss extreme scenarios, such as the preservation of women’s eggs.”

Masuda, who has also served as governor of Iwate, is concerned that the nation’s population decrease will accelerate, with Tokyo playing the role of a “black hole” absorbing the national population. The black hole will disappear in due course after absorbing everything from its surroundings.

On April 1, the municipal government of Masuda, Shimane prefecture, established a section exclusively dedicated to expanding the population. The city’s population, which peaked at around 73,000 in 1955, fell below 50,000 last year. It is anticipated to drop 10 percent more by 2020. Reversing this trend was a campaign pledge of Hiroaki Yamamoto, 44, who won his first term as mayor by beating the incumbent in the 2012 election.

Yamamoto has worked out a plan to achieve the goal of raising the city’s population to 50,500 in 2020. The city will provide subsidies to people relocating there and enrich assistance measures for child-rearing.

That the section was straightforwardly named the Population Expansion Section reflects how serious the city’s situation is.

Due to a manpower shortage, forests and rice paddies have been left desolated. The survival of some rural communities is threatened and it is difficult to maintain medical and welfare services.

Yamamoto attended a ceremony to mark the closing of municipal Mino Primary School last month. The abolition and consolidation of schools, though promoted for improving the educational environment, has a negative psychological impact on residents and may cause more young people to leave town. Speaking in front of the school’s last 14 students, the mayor resolved with all his heart “to definitely increase the population.”

Masuda is not an exception among regional cities. Last year, the Akita prefectural government established a group with the prefecture’s cities, towns and villages to study administrative issues in a shrinking society. The group is also researching integrated management of roads and bridges.

Theoretically, the country’s total population should not decline if young people moving from regional communities to the Tokyo metropolitan area still have many children. But the reality is different.

Various factors such as busy life and work conditions, cramped housing and insubstantial human relationships make young people hesitant to marry and start families. The growth of Tokyo’s elderly population creates demand for more medical and nursing care personnel, attracting still more young people to Tokyo from across the country. This leads to the sapping of regional communities in a “population black hole” phenomenon.

According to one estimate, Tokyo’s population is expected to peak at 13.35 million in 2020, when the Tokyo Olympics will be held. The wave of population decline hitting Tokyo will likely be bigger than those experienced by local areas, putting the elderly at a higher risk of isolation.

In the Higashi-Kurihara Public Housing Complex in Adachi ward, Tokyo, where 14 metropolitan apartment buildings stand, Mitsuharu Honma, 77, head of the complex’s residents association, makes the rounds at units where elderly people live alone. In 2012, there were four cases where elderly people died alone in the housing complex.

“First, I try to see if newspapers are piling up in a mailbox,” Honma said. Seventy percent of the residents in the complex are said to be 65 or older.

The Adachi ward office has enacted an ordinance enabling the provision of citizens’ information for community residents associations ― a rare step in Japan ― so that they can keep a close watch on the homes of elderly people on behalf of the ward.

By Atsushi Suwabe and Mioko Bo

(The Yomiuri Shimbun)

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[Today’s K-pop] BTS pop-up event to come to Seoul](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/17/20240417050734_0.jpg&u=)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240419100350)

![[Today’s K-pop] Zico drops snippet of collaboration with Jennie](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050702_0.jpg&u=)