Poster movement expands to gender discrimination

Term ‘kimchi woman’illustrates problems confronted by Korean women seeking job and stability

By Yoon Min-sikPublished : Jan. 19, 2014 - 20:06

Last month, a poster simply titled “How are you doing?” started a movement that urged South Korean college students to pay closer attention to what is going on in society. The politically charged movement has now expanded to a hot-button issue: discrimination against women.

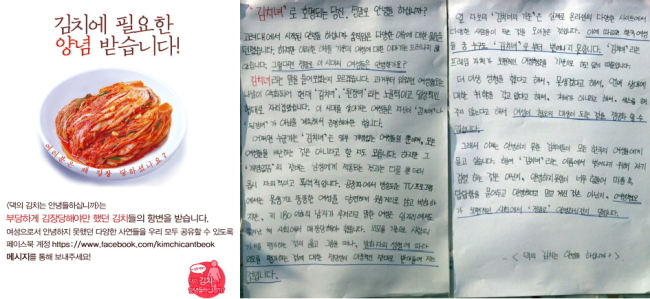

A poster criticizing the unfair treatment of women appeared on the campus of Korea University on Thursday.

It claimed that women are being forced to prove that they are not “kimchi women,” a derogatory term for a woman who financially relies on men and spends most of her money on beautifying herself.

“No Korean woman is free from being labeled kimchi woman, because the frame itself is based on the wide-spread culture of detesting women,” it said. “How are you really doing in such a society?”

The poster touched off a campaign called “How is your kimchi doing?” both online and offline. The campaign caused female students to submit stories about how they have been discriminated against because of their sex, or “branded a kimchi woman.”

One student said she had been urged to put on makeup because it was “good manners.” Another student said she was humiliated by a fellow male student for having small breasts.

Students pointed out the different standards applied to men and women.

They said that when a man does a foul deed, he is criticized as an individual. But when a woman does it, suddenly it becomes a problem for all Korean women.

One of the trends in Korean society is to make up a new term using the word “woman” whenever a woman does something that is frowned upon. For example, a young woman who did not clean up her dog’s feces on the subway was called “dog poop woman.”

The problem often cited with such a fad is that the criticism often does not just target the actions of that particular person, but expands to the condemnation of Korean women in general.

Some men pointed out they could also be a target of such discrimination. The term “kimchi man” is used to belittle South Korean men, usually against the fantasized high standards of Western men.

“When women are criticized on the Internet, people always say, ‘There goes a kimchi man again, being a total loser,’” said an office worker named Ju Jin-ho.

A student surnamed Kim said that many young women are financially dependent on men, which is why they are being criticized.

“We don’t call every woman in the world kimchi woman. We don’t call them kimchi woman for going to a better school or for making more money,” Kim said. “Kimchi women are those who don’t have jobs but spend money on expensive bags and those who blame sexual discrimination for every failure they go through.”

Even some female students acknowledge there is such a tendency.

“One of my friends referred to her new boyfriend as a ‘friend who pays for her meals.’ She said that she didn’t like him yet, but he was just a date-mate,” said a student from Hankuk University of Foreign Studies who wished to remain anonymous.

A civic group called “Man of Korea” has denounced what it called “adverse discrimination against men” ― referring to the practice in which men are expected to pay for the expenses for their female partners.

But paying for dates is just a small issue given that Korean women confront a wide range of disadvantages here, as demonstrated by the content of the new posters.

In a separate poster also put up at Korea University, a female student wrote that she was not “fine” because she had “no choice but to become a ‘kimchi woman.’” She claimed that when looking for a job, being a man is the best quality.

“For an ordinary woman to survive in this society, she becomes a kimchi woman. Because she has to meet an older man with a stable job, she has to stay young and beautiful, get plastic surgery and put on makeup,” she said.

While people of both sexes berated her for reducing the role of women to just meeting a wealthy partner, her poster touched on one key problem: Korean women continue to struggle in the fiercely competitive job market.

Research by the Korean Educational Development Institute showed that the employment rate among male college graduates was 60.1 percent in 2012, higher than 52.1 percent for their female counterparts.

The disparity widened among people who received higher education. Men with a master’s degree had a 76.4 percent chance of being employed while the figure for women stayed at 59.1 percent. For those with doctorate degrees, the rate was 78.4 percent for men and 59.5 percent for women.

The gap comes at a time when more women in their 20s are economically active than men of the same age group. In 2012, 62.9 percent of women in their 20s either had or were looking for a job, slightly surpassing men (62.6 percent) for the first time, according to data by Statistics Korea and the Ministry of Employment and Labor.

The rate is gloomier for those in their 30s: 93.3 percent for men and 56 percent for women.

South Korea also has the biggest wage gap between men and women among the members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development: Korean women on average make 1.54 million won a month, while men make 2.44 million won.

By Yoon Min-sik

(minsikyoon@heraldcorp.com)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240418181020)

![[Today’s K-pop] Zico drops snippet of collaboration with Jennie](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050702_0.jpg&u=)