Korea grapples with massive personal data theft, regulatory mess

ActiveX, public key system combine to open ‘black hole’ in cyber security

By Yoon Min-sikPublished : July 19, 2013 - 20:38

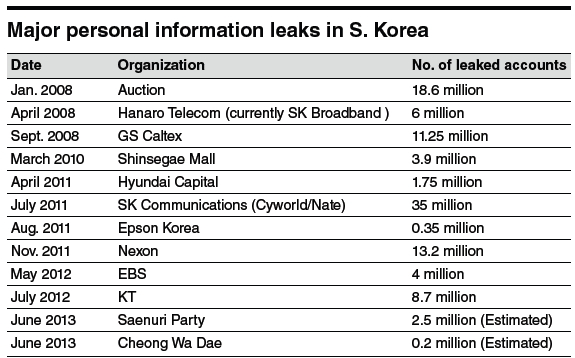

A string of cyber attacks have bombarded South Korea in recent years, leading to massive leaks of personal information stored in banks, government agencies and corporations.

In January 2008, hackers stole the personal data of some 18.6 million users of online shopping mall Auction. Three years later, SK Communications, which runs the online search engine Nate.com and social network service Cyworld, fell victim to data theft of its combined 35 million users ― roughly 70 percent of South Korea’s total population.

IT experts have suggested an array of factors behind those large-scale security lapses, with some blaming government-led overregulation such as the “public key certificate” system that is supposed to prevent such security breaches.

In January 2008, hackers stole the personal data of some 18.6 million users of online shopping mall Auction. Three years later, SK Communications, which runs the online search engine Nate.com and social network service Cyworld, fell victim to data theft of its combined 35 million users ― roughly 70 percent of South Korea’s total population.

IT experts have suggested an array of factors behind those large-scale security lapses, with some blaming government-led overregulation such as the “public key certificate” system that is supposed to prevent such security breaches.

Many Korean websites depend on Internet Explorer’s cumbersome “ActiveX” platform, posing another risk factor. KAIST professor Lee Min-hwa said, “ActiveX is a program that momentarily disarms the computer to download codes from an outside source, which can be abused by hackers seeking to plant malicious codes.”

Lee, one of the key patrons of President Park Geun-hye’s signature science and technology-based “creative economy,” said that Korea’s dependence on the ActiveX-based public key certificate system created a “black hole” in cyber security.

The public key certificate is a type of digital document that enables online transactions. Korea’s online regulations require that certificates should be issued for any transaction worth more than 300,000 won ($268), and the issuance also requires a download of proprietary software on Internet Explorer via ActiveX.

The mechanism, introduced in the late 1990s, is intended chiefly for South Korean citizens who use Microsoft Internet Explorer. Other Web browsers, such as Google’s Chrome, do not support ActiveX, and the whole system means foreigners often find it virtually impossible to purchase items on Korean websites.

The mix of ActiveX and the key certificate system was originally designed to protect personal data, but experts say it is now making computers in Korea more susceptible to cyber attacks and identity theft.

A user’s online key is often saved in a file on their PC, which can be easy prey for hackers, according to cyber security firm FireEye Inc.

Allowing people to save the key on a PC is also outside of international standards, said Kim Hyun-jun, system engineering manager of FireEye, adding that most Korean users keep their keys in their PCs.

Politicians have begun to notice the gravity of the issue. Rep. Lee Jong-kul of the Democratic Party recently proposed a bill to discontinue mandatory use of the online certificate for digital transactions.

Kim Kee-chang, professor of law at Korea University in Seoul and a critic of the public key certificate system, said the new bill would help prevent the government from interfering with people’s right to choose the technology they use to protect their computers.

“By allowing only the public key certificate to be used, the entire nation suffers inconvenience,” Kim said. “On top of that, countless online service providers are stuck on a single platform, blocking the broader IT industry from moving forward.”

The Financial Supervisory Service and companies involved seem to form a unified front to protect the existing system, as if it is the only viable option. But local online bookseller Aladdin recently put out a new payment system that works without the combination of ActiveX and the public key certificate.

Proponents of the current system, however, said it’s too early to terminate the public key certificate, arguing that there is a lack of viable alternatives. Its digital signature has been shown to be hard for hackers to penetrate, but critics said that while the mathematical algorithm behind the certificate is “near perfect,” the software it uses is far from risk-free.

The Science Ministry said Friday it is pushing to revise the current law to allow various means of verifying users’ identities for online transactions. The ministry plans to submit the revised bill to the National Assembly in September.

This is not the first time government counter cyber attack measures have been questioned. In February this year, Seoul required game operators, e-commerce firms and big websites to use the i-PIN instead of the 13-digit resident registration numbers to verify users’ identities.

The measure came after the resident registration numbers had long been targeted by hackers and misused by minors or those wanting to set up fake IDs. The trading of Koreans’ ID numbers among hackers and spammers in China and elsewhere led to greater security risks and personal data theft.

But the i-PIN has similar weaknesses. It also relies on the resident numbers and can divulge personal information when leaked. Thousands of i-PINs have already been illegally issued and sold to hackers and shady marketers in China.

Aside from technological issues, some experts said Korean companies tend to overlook the importance of cyber security.

Chun Kil-soo, an official with Korea Internet Security Center, is in charge of leading a response team against cyber attacks. He said companies rarely take action to fix the key security problems in their networks, allowing hackers to exploit the same weaknesses repeatedly.

The inaction stems from the lack of budget and manpower. According to KISA data, 73.3 percent of Korean companies do not earmark a dime to protect their data. Choi Young-chul, CEO of IT security software firm Red BC Co., said companies are reluctant to invest in cyber security because there’s no immediate return. “But if the accidents do happen, the damage could be enormous,” Choi said.

By Yoon Min-sik and Kim Jung-bo

(minsikyoon@heraldcorp.com) (jbsk_7465@heraldcorp.com)

![[AtoZ into Korean mind] Humor in Korea: Navigating the line between what's funny and not](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/22/20240422050642_0.jpg&u=)

![[Exclusive] Korean military set to ban iPhones over 'security' concerns](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050599_0.jpg&u=20240423183955)

![[Graphic News] 77% of young Koreans still financially dependent](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/22/20240422050762_0.gif&u=)

![[Herald Interview] Why Toss invited hackers to penetrate its system](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/22/20240422050569_0.jpg&u=20240422150649)

![[Exclusive] Korean military to ban iPhones over security issues](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050599_0.jpg&u=20240423183955)

![[Today’s K-pop] Ateez confirms US tour details](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050700_0.jpg&u=)