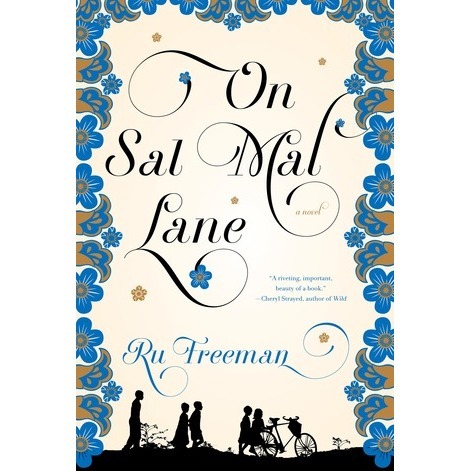

By Ru Freeman

(Graywolf Press)

In her rewarding new book, novelist Ru Freeman plunks readers “On Sal Mal Lane,” a tropical effusion of foliage and children growing up in Sri Lanka, the island off India’s southern tip. Colonialists once called the place Ceylon and prized its tea; Freeman, who grew up in the capital, Colombo, has something more pointed in mind.

Her story moves chronologically toward July 1983, or “Black July,” when riots in Colombo ignited a civil war lasting nearly 26 years. It takes 300 pages for this conflagration to reach the lane ― most of the book is preoccupied with cricket games and family life, setting the scene that will determine “who among them might be safe, who protected and who betrayed.”

Freeman’s first novel, “A Disobedient Girl,” is a Sri Lankan class and love story. This time, she writes in the voice of the street. “I am nothing more than the air that passed through these homes ... I am the road itself,” declares the odd, assertive prologue. The book begins stiffly, but settles into its cadences. A new family ― the Heraths ― has moved in, reconfiguring the play and pecking order along the lane.

At the start, the four Herath children are a unit, “every word uttered, every challenge made, every secret kept, together.” Their domestic loyalty is reminiscent of Louisa May Alcott’s March sisters, but Freeman divides her quartet into two brothers and two sisters, with the defiant, rambunctious youngest child, Devi, the focus of the family’s love and protection. The street also contains a bully, Sonna Bolling, and a Holy Fool, Raju Joseph. Both are beautifully realized, complex characters who disturb the peace and drive the plot.

Sonna and Raju, teenage boy and cognitively impaired man, vie for the Heraths’ affections. Raju wins out, becoming a kind of guardian to Devi in the afternoons. Everyone on the street ― Buddhist, Hindu, Muslim and Catholic ― has an opinion about the wisdom of this arrangement, which Freeman unsubtly aligns with Boo Radley and the Finch children. (One Herath boy reads “To Kill a Mockingbird” aloud.)

Indeed, the conflict between Sonna and Raju mirrors the escalating enmity between minority Tamils and majority Sinhalese. “On Sal Mal Lane” channels the mundane, organic ways in which social divisions can implode a once-peaceable place. The reader’s mind jumps easily to Sarajevo, Rwanda, Los Angeles.

When Freeman, a political essayist and activist, crosses the street into fiction, she faces the same problem as the Herath father, who “considered how best to describe the complexities of communal politics and guerrilla warfare to his children, all four of whom were looking at him with such quiet intensity.”

Despite a few portentous asides, “On Sal Mal Lane” succeeds, gathering gravitas and emotional depth. The sentences are not showstoppers, but the story is. Freeman makes it a choice reading destination.

(MCT)

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[From the Scene] Monks, Buddhists hail return of remains of Buddhas](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050617_0.jpg&u=20240419175937)

![[Graphic News] French bulldog most popular breed in US, Maltese most popular in Korea](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050864_0.gif&u=)

![[From the Scene] Monks, Buddhists hail return of remains of Buddhas](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050617_0.jpg&u=20240419175937)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240419100350)

![[Today’s K-pop] Illit drops debut single remix](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050612_0.jpg&u=)