Japan plans to build new rocket to replace aging H2A

By Korea HeraldPublished : June 10, 2013 - 20:08

The Office of National Space Policy has decided to develop a new mainline rocket to replace the H2A, with development set to begin next fiscal year and a first launch around 2020.

Eighteen years after work started on the H2A, the government hopes to enter the commercial launch market with the new rocket, in addition to sending up government satellites.

As another goal is to cut costs significantly, private-sector participation in the rocket’s development is a major issue.

“We’re aiming for around 2020, when new rockets from overseas are expected to start appearing,” Hiroshi Yamakawa, head of the Space Transport System Section at the office and professor of space engineering at Kyoto University, said after a meeting of his section May 28.

The space policy office is an advisory body to the prime minister that considers and makes proposals on matters such as space policy and budget allocation. It has seven part-time members and is chaired by Yoshiyuki Kasai, chairman of Central Japan Railways Co.

There are four specialist sections within the office. Yamakawa’s section, which is tasked with coming up with a national rocket strategy, was the one that decided to develop the new rocket.

The H2A has launched 22 information-gathering, environmental-observation and other satellites for the government. With only one failed launch, its 95 percent success rate has made it a standard for reliability around the world.

However, it has been largely absent from other fields, such as launching commercial communications and broadcast satellites or satellites for foreign countries. Its only launch that involved an entity besides the government, or domestic universities or research institutes, was when a South Korean multipurpose satellite hitched a ride in a 2012 launch.

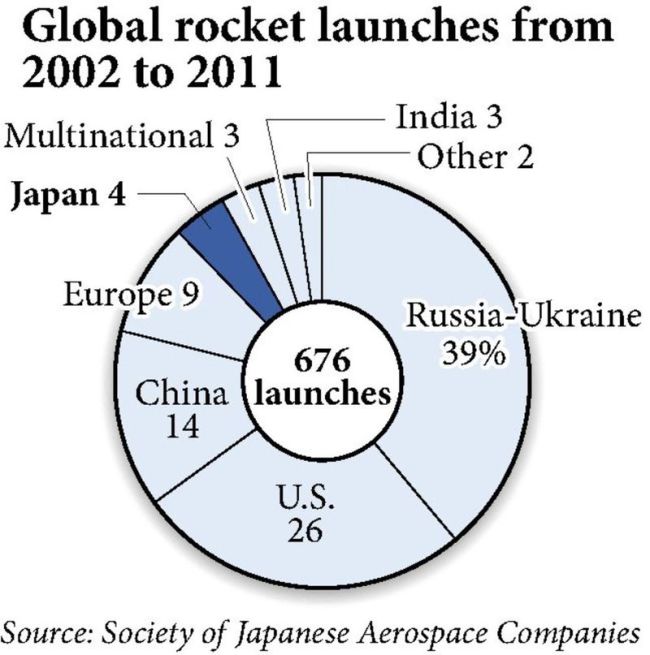

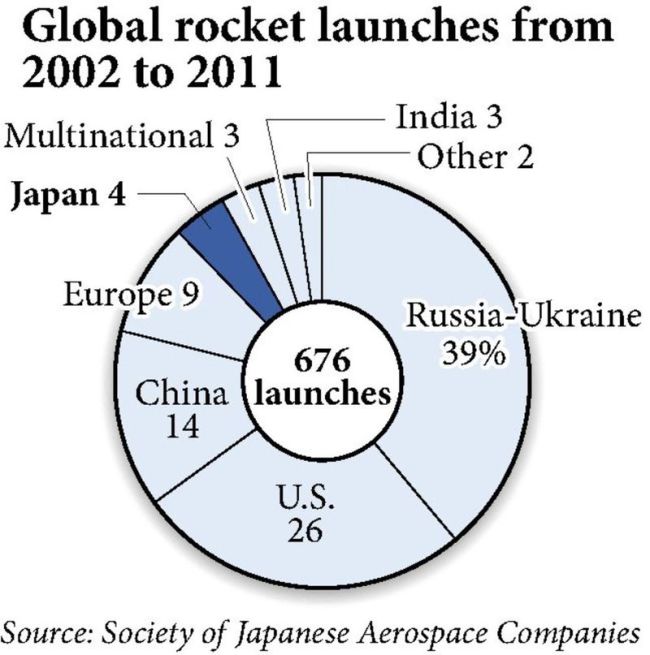

From 2002 to 2011, 676 rockets have been launched by governments and private companies around the world. Of these, Japan has launched 25, only 4 percent.

The about 10 billion yen ($101.7 million) it costs to launch each rocket is seen as a main reason behind this small number. Russian and Chinese rockets are cheaper, and a U.S. start-up company debuted the Falcon 9 in 2010, which costs about half as much as the H2A.

A cheaper version of the highly successful European Ariane 5 rocket is expected to arrive in 2021. The rocket’s launch site in French Guiana near the equator in South America is convenient for putting communications and broadcast satellites into geostationary orbit at an altitude of 36,000 kilometers.

Japan has been slow to adapt to the increased size of today’s satellites. The H2A was built to handle 4 tons, so it lacks the power to put communications and broadcast satellites and other 5-ton satellites into geostationary orbit.

Satellites are increasingly being built for long-term use, which adds weight with additional fuel and batteries.

The H2B uses two H2A engines and can carry an 8-ton load, and its only delivery success came when it helped the Kounotori unmanned spacecraft reach the International Space Station, which was in orbit 400 kilometers above the Earth. This rocket is not seen as capable of putting commercial satellites into orbit.

According to Masaharu Uji, head of space engineering at the Society of Japanese Aerospace Companies, “Japan needs to continue gaining launch experience, but also make progress in developing a rocket to handle larger satellites.”

The global market for satellite launches is about $4 billion annually and foreign rocket developers are competing fiercely to reduce costs. The space transport section seems to be aware that the H2A can no longer compete in the world market.

Security concerns are also behind the goal of around 2020 for the new rocket’s first launch. If the nation wants to continue to launch reconnaissance satellites, it needs to ensure it maintains the necessary rocket technology.

Almost 20 years have passed since development of the H2A began in 1996. By 2020, most researchers and engineers with developmental know-how will have retired. Rocket industry insiders are worried about a dearth of qualified workers if things continue as they are.

By Eiji Noyori and Masae Honma

(The Japan News)

Eighteen years after work started on the H2A, the government hopes to enter the commercial launch market with the new rocket, in addition to sending up government satellites.

As another goal is to cut costs significantly, private-sector participation in the rocket’s development is a major issue.

“We’re aiming for around 2020, when new rockets from overseas are expected to start appearing,” Hiroshi Yamakawa, head of the Space Transport System Section at the office and professor of space engineering at Kyoto University, said after a meeting of his section May 28.

The space policy office is an advisory body to the prime minister that considers and makes proposals on matters such as space policy and budget allocation. It has seven part-time members and is chaired by Yoshiyuki Kasai, chairman of Central Japan Railways Co.

There are four specialist sections within the office. Yamakawa’s section, which is tasked with coming up with a national rocket strategy, was the one that decided to develop the new rocket.

The H2A has launched 22 information-gathering, environmental-observation and other satellites for the government. With only one failed launch, its 95 percent success rate has made it a standard for reliability around the world.

However, it has been largely absent from other fields, such as launching commercial communications and broadcast satellites or satellites for foreign countries. Its only launch that involved an entity besides the government, or domestic universities or research institutes, was when a South Korean multipurpose satellite hitched a ride in a 2012 launch.

From 2002 to 2011, 676 rockets have been launched by governments and private companies around the world. Of these, Japan has launched 25, only 4 percent.

The about 10 billion yen ($101.7 million) it costs to launch each rocket is seen as a main reason behind this small number. Russian and Chinese rockets are cheaper, and a U.S. start-up company debuted the Falcon 9 in 2010, which costs about half as much as the H2A.

A cheaper version of the highly successful European Ariane 5 rocket is expected to arrive in 2021. The rocket’s launch site in French Guiana near the equator in South America is convenient for putting communications and broadcast satellites into geostationary orbit at an altitude of 36,000 kilometers.

Japan has been slow to adapt to the increased size of today’s satellites. The H2A was built to handle 4 tons, so it lacks the power to put communications and broadcast satellites and other 5-ton satellites into geostationary orbit.

Satellites are increasingly being built for long-term use, which adds weight with additional fuel and batteries.

The H2B uses two H2A engines and can carry an 8-ton load, and its only delivery success came when it helped the Kounotori unmanned spacecraft reach the International Space Station, which was in orbit 400 kilometers above the Earth. This rocket is not seen as capable of putting commercial satellites into orbit.

According to Masaharu Uji, head of space engineering at the Society of Japanese Aerospace Companies, “Japan needs to continue gaining launch experience, but also make progress in developing a rocket to handle larger satellites.”

The global market for satellite launches is about $4 billion annually and foreign rocket developers are competing fiercely to reduce costs. The space transport section seems to be aware that the H2A can no longer compete in the world market.

Security concerns are also behind the goal of around 2020 for the new rocket’s first launch. If the nation wants to continue to launch reconnaissance satellites, it needs to ensure it maintains the necessary rocket technology.

Almost 20 years have passed since development of the H2A began in 1996. By 2020, most researchers and engineers with developmental know-how will have retired. Rocket industry insiders are worried about a dearth of qualified workers if things continue as they are.

By Eiji Noyori and Masae Honma

(The Japan News)

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[Herald Interview] 'Amid aging population, Korea to invite more young professionals from overseas'](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/24/20240424050844_0.jpg&u=20240424200058)

![[KH Explains] Korean shipbuilding stocks rally: Real growth or bubble?](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/25/20240425050656_0.jpg&u=)