Will to change key to migrant policy

Korea must be open to accepting migrant workers for industrious future

By Korea HeraldPublished : April 24, 2013 - 20:20

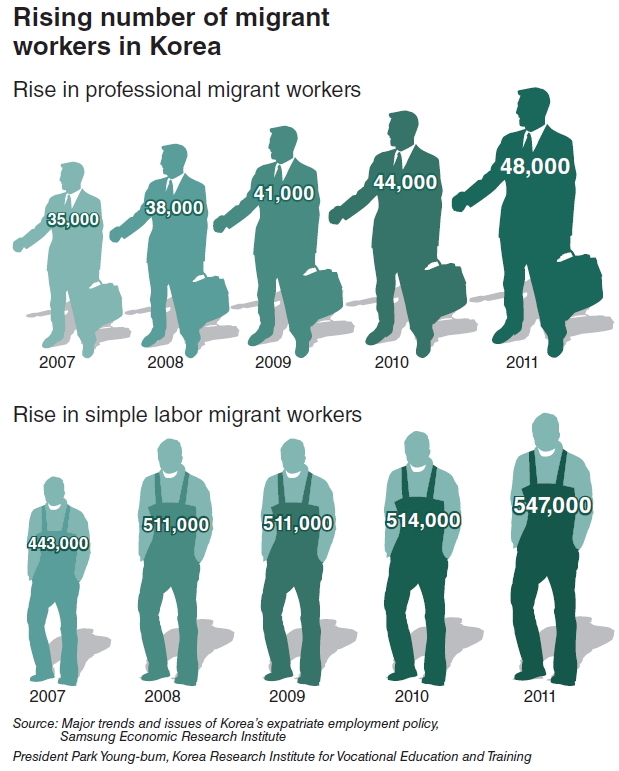

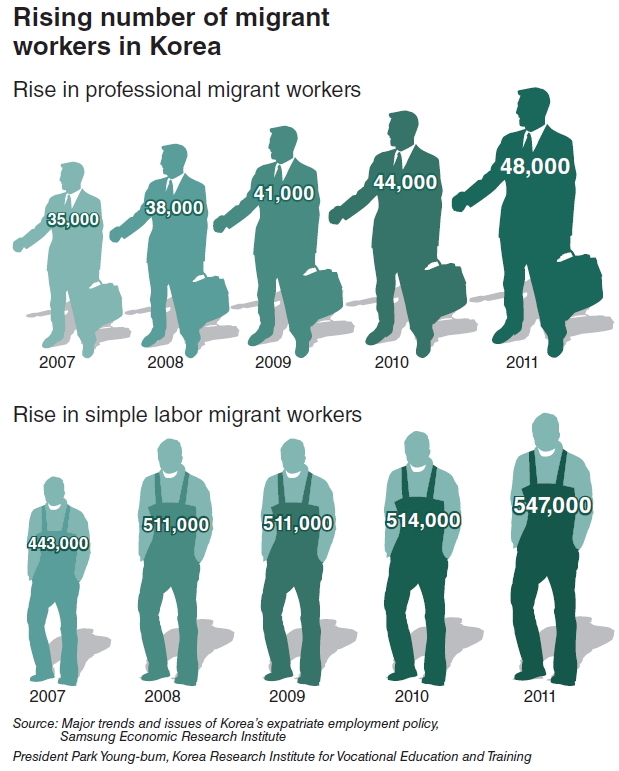

Korea began inviting foreign workers in 1993 to make up for labor shortages in smaller firms. In 2012, the nation hired 791,000 non-Koreans, according to Statistics Korea. A majority of alien workers toil in factories, restaurants and construction sites, filling the gaps left by the native workforce that is fast aging and increasingly shunning hard, low-paying jobs.

Despite their contribution to keeping the economy competitive, migrant workers are still suffering from exploitation, discrimination and suspicious eyes in a society that harbors fierce pride in its ethnic homogeneity.

According to the Joint Committee with Migrants in Korea, 78 percent experienced verbal abuse and 27 percent suffered physical abuse in 2011.

Female workers are vulnerable to sexual abuse. In a survey released in March, 35.5 percent said they had been raped, and another 35.5 percent experienced undesired physical contact. The perpetrators were mostly the business owners of their workplace.

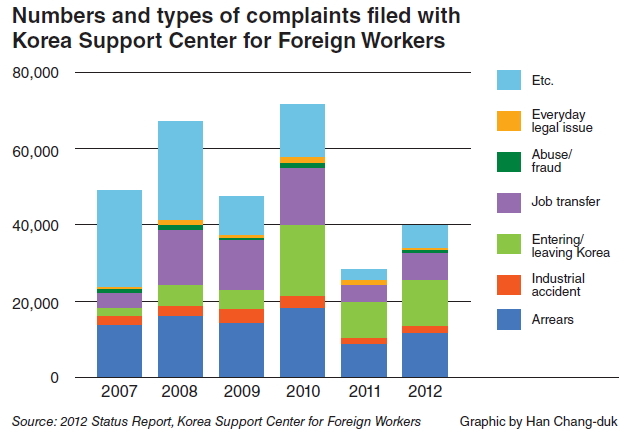

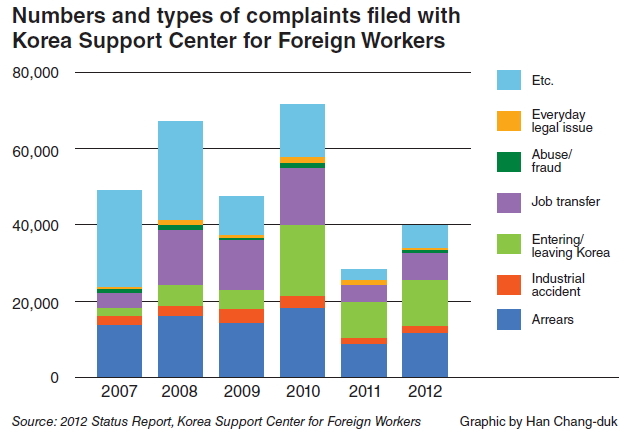

Some financially troubled companies take advantage of their weak legal and social status to delay wages and withhold benefits.

The current Employment Permit System guarantees all legal migrant workers the same working conditions as domestic workers. But many businesses violate the rules and foreign workers do not have proper access to legal justice due to the language barrier and their lack of knowledge of the complicated process.

“When migrant workers face abuse, they have difficulty seeking legal justice due to the language barrier,” said Lee Gun, assistant manager at Korea Support Center for Foreign Workers.

To seek legal help, migrant workers need documents such as records of payment, a doctor’s note and so on. Even migrants who have lived in Korea for many years cannot prepare all these documents on their own.

When Korea introduced the industrial trainee system in 1993, it was criticized for many loopholes that led to an increase in illegal workers and labor abuse. The government reinvented the scheme into the Employment Permit System in 2004.

Under the program Korea signs a bilateral agreement with foreign countries and their workers are allowed to work for an additional 22 months after finishing the initial employment period of three years.

To apply for the Employment Permit System, migrant workers must pass a series of Korean proficiency tests. However, they are written tests that require only very basic Korean. As a result, hopeful migrants do not learn how to actually communicate in Korean, but rather cram for the exam. Once they arrive, they find the language barrier to be even greater than they anticipated.

“Korea’s program for migrant workers is actually one of the best in the world. The Ministry of Employment and Labor manages migrant workers from their home, their time in Korean and back. The EPS may not be perfect, but the government is constantly making updates to improve migrants’ rights.” KSCFW President Lee Ha-ryong told the Korea Herald.

Despite their contribution to keeping the economy competitive, migrant workers are still suffering from exploitation, discrimination and suspicious eyes in a society that harbors fierce pride in its ethnic homogeneity.

According to the Joint Committee with Migrants in Korea, 78 percent experienced verbal abuse and 27 percent suffered physical abuse in 2011.

Female workers are vulnerable to sexual abuse. In a survey released in March, 35.5 percent said they had been raped, and another 35.5 percent experienced undesired physical contact. The perpetrators were mostly the business owners of their workplace.

Some financially troubled companies take advantage of their weak legal and social status to delay wages and withhold benefits.

The current Employment Permit System guarantees all legal migrant workers the same working conditions as domestic workers. But many businesses violate the rules and foreign workers do not have proper access to legal justice due to the language barrier and their lack of knowledge of the complicated process.

“When migrant workers face abuse, they have difficulty seeking legal justice due to the language barrier,” said Lee Gun, assistant manager at Korea Support Center for Foreign Workers.

To seek legal help, migrant workers need documents such as records of payment, a doctor’s note and so on. Even migrants who have lived in Korea for many years cannot prepare all these documents on their own.

When Korea introduced the industrial trainee system in 1993, it was criticized for many loopholes that led to an increase in illegal workers and labor abuse. The government reinvented the scheme into the Employment Permit System in 2004.

Under the program Korea signs a bilateral agreement with foreign countries and their workers are allowed to work for an additional 22 months after finishing the initial employment period of three years.

To apply for the Employment Permit System, migrant workers must pass a series of Korean proficiency tests. However, they are written tests that require only very basic Korean. As a result, hopeful migrants do not learn how to actually communicate in Korean, but rather cram for the exam. Once they arrive, they find the language barrier to be even greater than they anticipated.

“Korea’s program for migrant workers is actually one of the best in the world. The Ministry of Employment and Labor manages migrant workers from their home, their time in Korean and back. The EPS may not be perfect, but the government is constantly making updates to improve migrants’ rights.” KSCFW President Lee Ha-ryong told the Korea Herald.

Some Koreans still harbor the misconception that migrant workers are likely to commit crimes. Others cling to the “pure blood” idea that Koreans are homogenous and share the same blood. These ideas can heighten into aggression toward expatriates especially when the economy takes a downturn, president Lee explained.

“Rather than force integration, it is ideal to embrace migrants by expanding the boundary of a ‘citizen,’” senior researcher Choi Hong of Samsung Economic Research Institute told the Korea Herald.

The key is to ensure that migrants do not suffer discrimination from political and economic activities but accept and protect their unique traits such as religion, culture, community and beliefs, he explained.

In Swiss business school IMD’s 2010 research on national competitiveness, Korea ranked 52nd of 58 countries in the “cultural openness” category. To improve this, Korea needs to update its educational institutions so that students can have many opportunities to experience diverse cultures. Choi suggested also providing practical evidence that migrant workers contribute to the economy and do not steal jobs from Koreans.

The financial benefits of migrant workers are immediately observable, but the social cost of maintaining them are not apparent until later, Choi said, referring to European countries such as France and Germany.

“These countries accepted mass immigration in the 1960s to promote growth and supply manpower to key industries. If they had thought of the future impact of immigration, they would have prepared preventative measures for social conflict,” Choi said, referring to violent mass riots that periodically break out in France and England due to racial tension between native Europeans and migrant workers.

KSCFW President Lee also believed we must learn from Germany and France’s case.

“Those countries had policies that focused on ‘domesticating’ migrant workers to their society, rather than ‘incorporating’ them. However, migrants are segregated in impoverished slums, and face discrimination. This can only lead to social discontent and violence.

“To prevent such social tension from building in Korea, we must accept that multiculturalism is an inevitable trend. We must continue our efforts to help them become a part of our society.”

By Lee Sang-ju (sjlee370@heraldcorp.com)

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[Exclusive] Korean military set to ban iPhones over 'security' concerns](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050599_0.jpg&u=20240423183955)

![[Graphic News] 77% of young Koreans still financially dependent](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/22/20240422050762_0.gif&u=)

![[Pressure points] Leggings in public: Fashion statement or social faux pas?](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050669_0.jpg&u=)