자신의 블로그를 통해 암 재발 사실을 공개하고 재활 의지를 보인 지 불과 만 하루만이다.

이버트는 지난 3일 새벽 "골반 골절상 치료 과정에서 암 재발을 확인했으며 치료에 집중하기 위해 평론 일선에서 잠정 물러난다"고 밝힌 바 있다.

그는 "당분간 활동을 자제하겠지만 엄선된 작품에 대해서는 평론을 계속 내놓겠다"며 영화에 대한 열정을 놓지 않았다.

그러면서도 팬들에게 "지금까지 긴 여정에 함께 해준 여러분께 다시 한 번 감사한다. 영화를 통해 만나자"는 마지막 인사를 남겼다.

신문과 방송에서 종횡무진으로 활동한 저널리스트이고 영화 평론계의 '큰 별'로 여겨진 이버트의 사망 소식이 전해진 후 백악관을 비롯한 미국 전역에 애도 물결이 이어지고 있다.

버락 오바마 대통령은 성명에서 "이버트는 암과 싸우는 와중에도 왕성하게 활동하면서 그의 열정과 관점을 세상과 공유했다. 이버트가 떠난 영화계는 이전과 같을 수 없을 것"이라고 애도했다.

오바마 대통령은 "이버트는 영화 그 자체였다"며 "이버트는 좋아하지 않는 영화에 대해 진솔했다. 좋아하는 영화를 만났을 경우에는 그 영화가 지닌 독특한 파워를 끄집어내 우리를 마법의 세계로 인도했다"고 평했다.

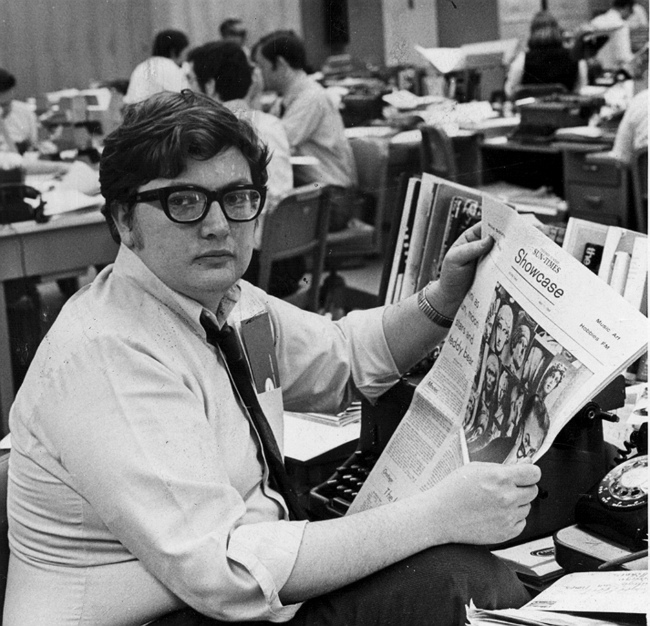

일리노이주 어바나 출신으로 일리노이대학과 시카고대학원을 졸업한 이버트는 1967년부터 46년 동안 시카고 선타임스에서 영화담당기자와 영화평론가로 일했다.

1975년에는 영화 비평으로는 처음으로 평론 부문 퓰리처상을 받았고 2005년에는 할리우드 명예의 거리에 이름을 올렸다. 그가 저술한 책은 15편에 이른다.

이버트는 1975년부터 20여 년간 시카고 트리뷴 기자 진 시스켈(1946~1999)과 함께 진행한 TV 영화비평 프로그램으로 대중적인 인기를 얻었다.

이버트와 시스켈이 엄지손가락을 치켜들거나 내리는 제스처로 영화를 평가하면서 최고의 영화평에 '투 섬스 업'(Two Thumbs Up)이란 말이 붙기도 했다.

그러나 시스켈이 뇌종양으로 세상을 떠난 지 3년 만인 2002년 이버트도 갑상선암과 침샘종양 선고를 받고 수술과 재활을 반복했다.

2006년에는 턱 제거 수술을 받아 말하거나 음식을 먹을 수 없게 됐지만 2010년 달라진 외모를 당당히 공개하고 대외활동을 재개했다.

이버트는 시카고 선타임스 블로그를 통해 영화평을 발표하고 소셜미디어로 팬들과 소통하면서 변함없는 역량을 과시해왔다.

지난해 그가 발표한 영화평론은 300여 편, 그의 트위터 팔로워는 82만7천명에 이른다.

그는 지난 1992년 흑인 여성 채즈 해멀스미스와 결혼했으며 입양한 두 자녀와 네 명의 손주를 뒀다.(연합뉴스)

<관련 영문 기사>

Famed movie critic Roger Ebert dies at age 70

Roger Ebert, the most famous and popular film reviewer of his time who became the first journalist to win a Pulitzer Prize for movie criticism and, on his long-running TV program, wielded America's most influential thumb, died Thursday. He was 70.

Ebert, who had been a film critic for the Chicago Sun-Times since 1967, died Thursday at the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago, his office said. Only a day earlier, he announced on his blog that he was undergoing radiation treatment after a recurrence of cancer.

America's best-known movie reviewer “wrote with passion through a real knowledge of film and film history, and in doing so, helped many movies find their audiences,” director Steven Spielberg said. His death is “virtually the end of an era, and now the balcony is closed forever.”

Ebert had no grand theories or special agendas, but millions recognized the chatty, heavy-set man with wavy hair and horn-rimmed glasses. Above all, they followed his thumb _ pointing up or down. It was the main logo of the televised shows Ebert co-hosted, first with Gene Siskel of the rival Chicago Tribune and _ after Siskel's death in 1999 _ with his Sun-Times colleague Richard Roeper.

Although criticized as gimmicky and simplistic, a “two thumbs-up” accolade was sure to find its way into the advertising for the movie in question.

On the air, Ebert and Siskel bickered like an old married couple and openly needled each other. To viewers who had trouble telling them apart, Ebert was known as the fat one with glasses, Siskel as the thin, bald one.

Despite his power with the movie-going public, Ebert considered himself “beneath everything else a fan.”

“I have seen untold numbers of movies and forgotten most of them, I hope, but I remember those worth remembering, and they are all on the same shelf in my mind,” Ebert wrote in his 2011 memoir, “Life Itself.”

He was teased for years about his weight, but the jokes stopped abruptly when Ebert lost portions of his jaw and the ability to speak, eat and drink after cancer surgeries in 2006. He overcame his health problems to resume writing full-time and eventually even returned to television. In addition to his work for the Sun-Times, Ebert became a prolific user of social media, connecting with fans on Facebook and Twitter.

In early 2011, Ebert launched a new show, “Ebert Presents At the Movies.” It had new hosts, but featured Ebert in his own segment, “Roger's Office.” He used a chin prosthesis and enlisted voice-over guests to read his reviews.

While some called Ebert a brave inspiration, he told The Associated Press in an email in January 2011 that bravery and courage “have little to do with it.”

“You play the cards you're dealt,” Ebert wrote. “What's your choice? I have no pain. I enjoy life, and why should I complain?”

Ebert joined the Sun-Times part-time in 1966 while pursuing graduate study at the University of Chicago and got the reviewing job the following year. His reviews were eventually syndicated to several hundred other newspapers, collected in books and repeated on innumerable websites, which would have made him one of the most influential film critics in America even without his television fame.

His 1975 Pulitzer for distinguished criticism was the first, and one of only three, given to a film reviewer since the category was created in 1970. In 2005, he received another honor when he became the first critic to have a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.

Ebert's breezy and quotable style, as well as his knowledge of film technique and the business side of the industry, made him an almost instant success.

He soon began doing interviews and profiles of notable actors and directors in addition to his film reviews _ celebrating such legends as Alfred Hitchcock, John Wayne and Robert Mitchum and offering words of encouragement for then-newcomer Martin Scorsese.

In 1969, he took a leave of absence from the Sun-Times to write the screenplay for “Beyond the Valley of the Dolls.” The movie got an “X” rating and became somewhat of a cult film.

Ebert's television career began the year he won the Pulitzer, first on WTTW-TV, the Chicago PBS station, then nationwide on PBS and later on several commercial syndication services. Ebert and Siskel even trademarked the “two thumbs-up” phrase.

And while the pair may have sparred on air, they were close off camera. Siskel's daughters were flower girls when Ebert married his wife, Chaz, in 1992.

“He's in my mind almost every day,” Ebert wrote in his autobiography. “He became less like a friend than like a brother.”

Ebert was also an author, writing more than 20 books that included two volumes of essays on classic movies and the popular “I Hated, Hated, Hated This Movie,” a collection of some of his most scathing reviews.

The son of a union electrician who worked at the University of Illinois' Urbana-Champaign campus, Roger Joseph Ebert was born in Urbana on June 18, 1942. The love of journalism, as well as of movies, came early. Ebert covered high school sports for a local paper at age 15 while also writing and editing his own science fiction fan magazine.

He attended the university and was editor of the student newspaper. After graduating in 1964, he spent a year on scholarship at the University of Cape Town in South Africa and then began work toward a doctorate in English at the University of Chicago.

Ebert's hometown embraced the film critic, hosting the annual Ebertfest film festival and placing a plaque at his childhood home.

Ebert also was embraced online in the years after he lost his physical voice. He kept up a Facebook page, a Twitter account with nearly 600,000 followers and a blog, Roger Ebert's Journal.

The Internet was where he forged relationships with his readers, posting links to stories he found interesting and writing long pieces on varied topics, not just film criticism. He interacted with readers in the comments sections and liked to post old black-and-white photos of Hollywood stars and ask readers to guess who they were.

“My blog became my voice, my outlet, my `social media' in a way I couldn't have dreamed of,” Ebert wrote in his memoir. “Most people choose to write a blog. I needed to.”

Ebert wrote in 2010 that he did not fear death because he didn't believe there was anything “on the other side of death to fear.”

“I was perfectly content before I was born, and I think of death as the same state,” he wrote. “I am grateful for the gifts of intelligence, love, wonder and laughter. You can't say it wasn't interesting.” (AP)

![[Exclusive] Korean military set to ban iPhones over 'security' concerns](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050599_0.jpg&u=20240423183955)

![[Pressure points] Leggings in public: Fashion statement or social faux pas?](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050669_0.jpg&u=)

![[Herald Interview] 'Amid aging population, Korea to invite more young professionals from overseas'](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/24/20240424050844_0.jpg&u=20240424200058)