Uncertainty looms over Sino-American rivalry

For early 21st century, their relationship likely to be a blend of partnership and rivalry

By Korea HeraldPublished : Nov. 19, 2012 - 20:53

This is the fifth in a series of articles on the growing rivalry between the U.S. and China and its implications for the two Koreas and East Asia. ― Ed.

The growing Sino-American rivalry has raised the question of whether their relationship will descend into a zero-sum contest for global primacy or continue to be a strategic mixture of collaboration and competition.

Experts presume the latter is the most plausible for the next few decades, given their gaps in power, and domestic challenges. But it is still an open-ended question whether China will remain content with the status quo amid its growing power.

“At most, China will become a cautious and timid revisionist. For the years to come, China will remain as a status-quo power, since this situation has served China well,” Cheng Xiaohe, international studies professor at Renmin University of China, told The Korea Herald via email.

“China has no overwhelming reasons to reverse such a policy. Nonetheless, China will try to put its own mark on various international organizations in a gradualist, rather than revolutionary way.”

Lee Choon-kun, security expert at the Korea Economic Research Institute, forecast heightened tension between the two for the next decade, during which new leader Xi Jinping is at the helm of the emerging global power.

“Both the U.S. and China may take a strong stance (toward each other) and their conflict could be further heightened,” he said.

“Now for the second term, President Barack Obama is given a free hand to adopt a more active foreign policy. As for Xi, nationalism could come into play as he seeks to address growing public grievances.”

The two powers’ competition has been intensifying as the Asia-Pacific emerges as the center of power and wealth.

China has been increasingly assertive in recent years, taking issue with what it sees as unfair aspects of the U.S.-led international order since the end of World War II. Its muscle flexing over territorial disputes in the East and South China Seas has also put its neighbors as well as U.S. allies on edge.

Washington has repeatedly urged China to play by the rules, while striving to maintain its global preponderance amid the “rise of the rest” and reassure its allies and partners of its security commitments.

The growing Sino-American rivalry has raised the question of whether their relationship will descend into a zero-sum contest for global primacy or continue to be a strategic mixture of collaboration and competition.

Experts presume the latter is the most plausible for the next few decades, given their gaps in power, and domestic challenges. But it is still an open-ended question whether China will remain content with the status quo amid its growing power.

“At most, China will become a cautious and timid revisionist. For the years to come, China will remain as a status-quo power, since this situation has served China well,” Cheng Xiaohe, international studies professor at Renmin University of China, told The Korea Herald via email.

“China has no overwhelming reasons to reverse such a policy. Nonetheless, China will try to put its own mark on various international organizations in a gradualist, rather than revolutionary way.”

Lee Choon-kun, security expert at the Korea Economic Research Institute, forecast heightened tension between the two for the next decade, during which new leader Xi Jinping is at the helm of the emerging global power.

“Both the U.S. and China may take a strong stance (toward each other) and their conflict could be further heightened,” he said.

“Now for the second term, President Barack Obama is given a free hand to adopt a more active foreign policy. As for Xi, nationalism could come into play as he seeks to address growing public grievances.”

The two powers’ competition has been intensifying as the Asia-Pacific emerges as the center of power and wealth.

China has been increasingly assertive in recent years, taking issue with what it sees as unfair aspects of the U.S.-led international order since the end of World War II. Its muscle flexing over territorial disputes in the East and South China Seas has also put its neighbors as well as U.S. allies on edge.

Washington has repeatedly urged China to play by the rules, while striving to maintain its global preponderance amid the “rise of the rest” and reassure its allies and partners of its security commitments.

The Obama administration has put forward its “rebalancing” policy as the U.S. shifts its policy focus toward the economically vibrant region from the volatile Middle East and financially strained Europe, after a decade of war in Iraq and Afghanistan.

“The future of politics will be decided in Asia, not Afghanistan or Iraq, and the U.S. will be right at the center of the action,” U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton said in an atticle in U.S.-based Foreign Policy magazine last November.

China has been unnerved, apparently taking the move as part of Washington’s stepped-up efforts to hem it in or thwart what it terms a peaceful rise, despite Washington’s denials.

Washington’s virtual exclusion of China from its Tran-Pacific Partnership scheme to forge a free-trade zone encompassing the Asia-Pacific region has further fanned a sense of antagonism between the established and emerging powers.

Whatever their true intentions may be, their growing rivalry is expected to put Seoul in a difficult diplomatic position given that it should maintain its long-standing alliance with the U.S. without compromising the strategic ties with its largest trading partner China ― the strong patron and ally of nuclear-armed North Korea.

Rising or revival

Westerners have said China is rising or emerging, which bears both positive and negative connotations.

Liberalist theorists contend the rise of China, with its big market and massive human resources, means opportunities for the international community, and greater contributions to global prosperity, peace and security.

Realists, however, caution against the likelihood of China’s pursuing a hegemonic power while translating its economic strength into a greater military might, which could hamper America’s global power projection.

Whatever outsiders’ perspectives are, China likes to say it is pursuing a “revival of a strong nation” to avoid repeating its history of suffering foreign invasions in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Opium War (1840-42) was China’s most traumatic confrontation with the West. It resulted in the unfair Nanking Treaty involving its relinquishing of Hong Kong to Britain. China’s defeat in the Sino-Japanese War (1894-95) and Imperial Japan’s invasions during World War II remain another historical trauma.

Although China is proud of its newfound strength, it apparently wants to avoid any implicit call for it to take on more global responsibilities, as it is already swamped with a plethora of domestic challenges.

Washington has urged Beijing to become a “responsible stakeholder” in the region and beyond as part of the Group of Two. Since it surpassed Japan as the world’s second-largest economy in 2010, the media have called China part of the G2.

China’s nominal gross domestic product is expected to surpass that of the U.S. in around 2020. China now has the world’s largest foreign currency reserve, and holds $1.15 trillion worth of U.S. treasury bills.

China as potential revisionist

China-bashing has always been a dominant theme in U.S. presidential debates over foreign policy, apparently underscoring America’s growing concerns about China’s increasing military and economic clout.

Candidates’ rhetoric was sharper than ever this year. President Obama labeled China as an “adversary” for the first time, contradicting his hitherto collaborative stance. His Republican rival Mitt Romney branded it a “currency manipulator.”

Experts concur China may not pursue adventurism for the next decade during Xi’s presidency in the face of daunting challenges at home, although it may continue to raise its voice over what it views as unfair in the international order.

China’s domestic conundrums include the massive gap between the rich coastal areas and the underdeveloped western regions, the more general gulf between the rich and poor, its opaque political system, corruption in officialdom, and demographic challenges stemming from its one-child policy.

“Xi may try to reconcile two nations’ interests by adopting a pragmatic and cooperative policy toward the U.S.,” said Cheng Xiaohe of Renmin University.

“As China tries to cope with the hot issues on its periphery, China will have no interest in any heightened confrontation with the U.S. even though the two nations might run into conflicts of interest from time to time.”

To become a revisionist that could challenge the U.S., China still lacks both hard and soft power, experts noted. To top it off, China is the nation which has benefited most from the U.S.-led capitalist mechanism, they said.

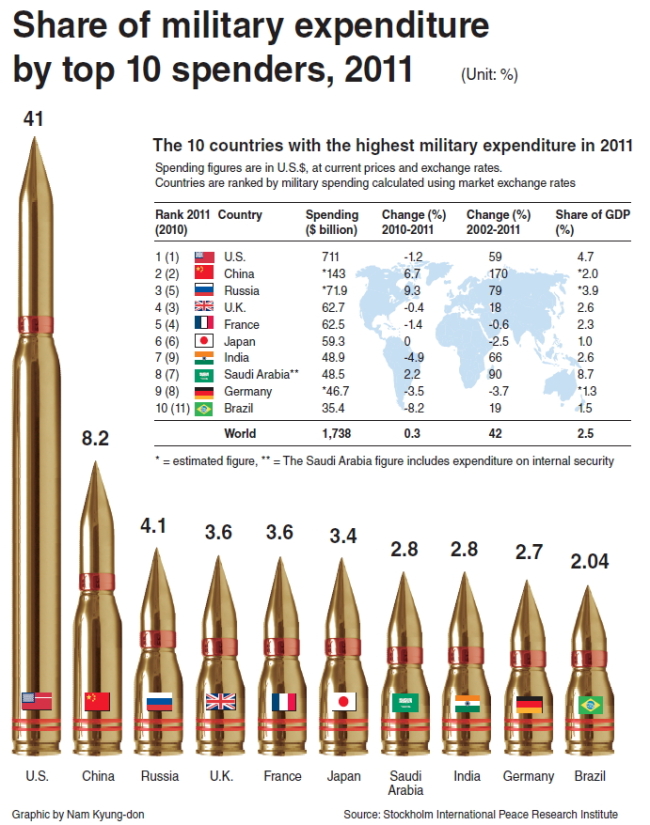

According to data from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, America’s military expenditure was $711 billion in 2011 while that of China was at $143 billion. The United States’ nominal GDP was $14.5 trillion in 2010 while China’s was $5.9 trillion, according to the International Monetary Fund.

For the U.S. as well, the best policy for now is to maintain the status quo as it struggles with a sluggish economic recovery, massive national debt, high unemployment and volatility in the Middle East.

“I expect to see the U.S. to continue a policy of deep diplomatic engagement with China combined with a reweighting of its strategic interests in the direction of Asia,” said Scott Snyder, a senior fellow at the U.S.-based Council on Foreign Relations.

“Every U.S. effort to enhance relations with other countries in Asia should not automatically be assumed to come at China’s expense.”

However, China’s increasing assertiveness in maritime disputes with U.S. allies and partners including Vietnam and the Philippines poses a tough challenge to the U.S.

Washington apparently believes Beijing’s “anti-access area-denial” capabilities could hamper its regional power projection and undermine what it calls the “global commons” it has long promoted to secure freedom of commerce and navigation.

“Neighboring states apparently feel threatened (by China’s military influence), irrespective of China’s true intentions,” said Kim Heung-kyu, China expert at Sungshin Women’s University.

“Through strategic communication between China and the U.S., and China and neighboring states, they continue to address their misunderstandings. China, for its part, should recognize how its bolstered military could threaten its neighbors.”

Challenges for the U.S. that could hamper its “rebalancing” efforts include its financial constraints and Middle East conundrums including Iran’s nuclear programs and frayed ties with the geo-strategically crucial Pakistan.

Growing military rivalry

One of the most pressing concerns for the U.S. military is China’s anti-access/area-denial capabilities based on its military modernization in all domains including space and cyberspace, experts said.

They noted America’s failure to counter it could constrain its regional power projection and cause its allies and partners to worry about its security commitments and consider leaning toward China.

Mindful of this, the U.S. has been refocusing its military priorities on the Asia-Pacific despite its cuts in defense spending to tackle a fiscal deficit.

“Unless the U.S. demonstrates its strength and will to defend (its allies and partners), they are likely to cooperate with the country that poses a potential threat to them ― what theorists call bandwagoning behavior,” said Kim Heung-kyu, China and security expert at Sungshin Women’s University.

Washington plans to increase the portion of its battleships stationed in the region from the current 50 percent to 60 percent by 2020. The ships would include six aircraft carriers.

“The U.S. maintains its lead in the state-of-the-art defense technologies and full-spectrum military capabilities, which can’t be matched by China,” said Michael Raska, research fellow at the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, Nanyang Technological University.

“Accordingly, the Chinese have been investing considerable resources and making progress in developing a diverse portfolio of asymmetric capabilities for air, sea and land operations that may offset select U.S. advantages.”

To counter China’s perceived military threats, the U.S. is fleshing out its AirSea Battle concept featuring integrated aerial and naval operations across all domains such as air, sea, space and cyberspace.

The concept involves three key phases ― a “Blinding Campaign” to deny the enemy’s situational awareness by neutralizing its intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance assets; a missile suppression campaign to disrupt the enemy’s air-defense networks and achieve air superiority; and lastly follow-on operations to seize the operational initiative.

But the concept has been hindered by strategic ambiguity and uncertain operational consequences, Raska pointed out.

“U.S. allies in the region question whether and to what extent the ASB foresees active allied participation in the envisioned ‘deep-strike missions’ targeting China’s surveillance systems and the long-range missiles dispersed across the mainland,” he said.

This and other U.S. military efforts have been intensified as China has constantly modernized its military capabilities with high-tech weapons systems.

Particularly, to expand its maritime defense, China has focused on developing sea-launched ballistic missiles and anti-ship ballistic missiles with diversified striking ranges and enhanced precision-strike capabilities. ASBMs are dubbed “aircraft carrier killers.”

In September, China put into service the 67,500-ton Liaoning aircraft carrier, showing off its maritime ambitions to raise a blue-water navy. It has also unveiled its stealth J-20 fighter jets.

But Raska said that converting available resources into increased military capabilities involves much more diverse, complicated efforts.

“The conversion is bound to the organizational adaptability, efficiency, and effectiveness of a country’s defense planning and management to attain better efficiency gains, cost savings, innovation and competitiveness to maximize the operational performance of its armed forces,” he said.

“Accordingly, China has to overcome existing structural, organizational, doctrinal and technological deficiencies in order to close the gap with the technologically superior and operationally experienced U.S. military.”

Possibility of another Cold War rigidity

As the Sino-American rivalry has loomed large, so has the specter of another Cold War.

However, experts largely dismiss a pessimistic view of their rivalry, stressing that deepening economic interdependence in the “WTO era,” any serious conflict between them would cause economic damage for both.

“As their economies were clearly separated during the Cold War, their hostile relationship did not inflict any serious economic damage on each other,” said Suh Jin-young, professor emeritus at Korea University. “Until about two decades ago, the U.S. was able to harass China through economic means without itself being hurt at all. But now, things have changed.”

On top of the intricate web of economic ties, online communities could play a crucial role in forging transnational discourse against the two powers’ confrontational move given that it could bring about negative ramifications for the entire capitalist world.

The so-called balance of nuclear terror based on fears of “mutually assured destruction” still continues on amid the nuclear powers’ competition, experts noted.

Beyond the possibility of their military clashes, there are many transnational issues that call for their joint action. They include climate change, proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, terrorism and piracy off the Somali coast.

What China lacks to be a great power

China is nearing the status of a global power by many accounts. That, however, stems largely from hard, material power, experts noted, stressing that it should pay more heed to enhancing its “soft power.” Soft power ― a term coined by Joseph Nye of Harvard University ― is based on intangible influences such as values, ideals and norms.

“China, affected by nationalism at home, showed off its military power in a manner that threatens its neighbors when territorial conflicts flared up, rather than trying to use multilateral cooperation channels to resolve them,” said Sohn Byoung-kwon, political science professor at Chung-Ang University.

“To gain the due qualification for the global leadership equivalent to that of the U.S., it should first address its neighbors’ concerns. It is already a strong nation militarily and economically, but (not) in the realm of soft power.”

Lee of the Korea Economic Research Institute stressed that China should first institutionalize the three “universal values” of democracy, freedom and peace to become a great power.

“As they always mention peace, China claims to have that value. But in terms of the other two, it has a long way to go yet,” he said. “In addition to that, we talk about China’s total economic size to surpass the U.S. in the coming decade. But, in history, there were no great powers, in which their people were poor.”

Above all, what China should not forget is that it is not rising in a vacuum, but with many other peers in the international community, experts said. For this reason, it should gain “recognition” from others to have the genuine global leadership.

“Recognition is rarely given just because of its size or (hard, material) power. It comes along when it makes donations to enhance the public good, appeals to them with its own culture and charm,” said Kim of Sungshin Women’s University.

Apparently aware of these concerns about soft power, China has launched what experts call a “charm offensive” to enhance its soft power in Southeast Asia, Central Asia, sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America through massive business investment, development assistance and other tools using its material power.

Some disparage such Chinese soft-power efforts as part of a strategy to secure oil and other resources from the underdeveloped countries, in order to power its economy and feed its 1.3 billion people.

But some positively compare this foreign policy to the United States’ Marshall Plan (1947-51), which helped reconstruct European economies after the end of World War II and stem communist expansion.

By Song Sang-ho (sshluck@heraldcorp.com)

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[Herald Interview] 'Amid aging population, Korea to invite more young professionals from overseas'](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/24/20240424050844_0.jpg&u=20240424200058)

![[KH Explains] Korean shipbuilding stocks rally: Real growth or bubble?](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/25/20240425050656_0.jpg&u=)