Korea-China economic ties face new opportunities, challenges

By Korea HeraldPublished : Aug. 13, 2012 - 20:16

The economic interdependence between Korea and China has grown rapidly ever since the two countries established diplomatic ties 20 years ago and is expected to increase further despite changing circumstances.

The two-way trade volume has snowballed nearly 35-fold since 1992, making China Korea’s biggest trading partner.

Both being export-driven economies, Korea and China share similar economic values and experiences, as they went through globalization in the 1990s and sought East Asian economic integration in the 2000s.

Korea became the only major trading partner to recognize China’s market economy status in 2005. The U.S., Japan and the European Union still have not.

With over 20,000 Korean businesses investing in China, the two have mutually benefited from processing trade, in which China imports intermediary goods such as parts from Korea and re-exports the finished products after processing or assembly.

However, the neighboring nations’ economic partnership, which has developed with China’s emergence as “the factory of the world,” now faces new opportunities and challenges as the world’s second-largest economy is turning into the world’s biggest market for many goods including cars, groceries and gold.

Trade and investment

The International Monetary Fund said earlier this month that for every 1 percentage point drop in China’s investment growth, Korea’s economic growth would decline by 0.6 percent point annually.

Korea would be the third-hardest hit country after Malaysia and Taiwan if China’s investment growth slows, the IMF said.

Similarly, Hyundai Research Institute said in a recent report that for every 1 percentage point fall in China’s economic growth, Korea’s growth would slow by 0.4 percent point.

Such close correlation is primarily attributed to the two countries’ strong interdependence in trade.

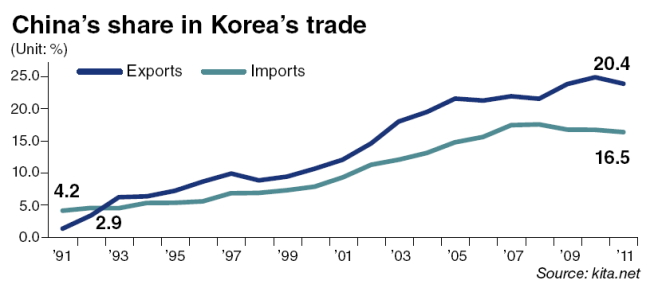

China accounts for nearly a quarter of Korea’s total exports, and Korea is the second-largest exporter to China after Japan. Korea is also the fourth-biggest importer from China after the U.S., Hong Kong and Japan.

Trade between Korea and China jumped from $6.3 billion in 1992 to $220.6 billion last year, bigger than Korea’s annual trade volumes with the U.S. ($100.9 billion) and the European Union ($103.1 billion) combined.

Of the $220.6 billion, $134.2 billion was Korea’s exports to China, translating into a trade surplus of some $47.75 billion with the world’s second-largest economy.

Korea’s trade surplus with China helped the fourth-largest economy in Asia quickly recover from the global financial crisis in 2008.

Korea’s accumulated trade surplus with China over the past two decades amounted to $272.5 billion, greater than its total accumulated trade surplus in the same period ($239.7 billion).

The two countries have recently begun negotiations for a bilateral free trade agreement, which is expected to further boost trade, and plan to start bargaining for a trilateral FTA with Japan this year.

The envisioned trade pact between Korea and China would be the first FTA within East Asia and therefore a stepping stone and model for the region’s economic integration.

The Korea International Trade Association said in a recent report that despite the fact that exports to China contributed greatly toward Korea’s economic growth since the beginning of bilateral ties 20 years ago, several problems need to be handled.

The first is Korea’s huge dependence on exports to China, which makes it vulnerable to the risks of the Chinese economy such as slowing growth or investment.

The relatively high proportion of processing exports to China is another alarming factor as the advancement of the Chinese industrial structure and technological improvement will lighten China’s demand for processing imports, KITA said.

China’s other major trading partners have already started to increase exports of final goods while reducing processing trade.

“Since the Chinese government is seeking to deviate from its preferential policies for processing trade, Korean businesses engaging mostly in processing trade with China will soon be negatively affected,” said Chung Hwan-woo, a researcher at KITA’s Institute for International Trade.

Chung advised these companies to make more efforts to explore the Chinese domestic market.

Korea is also losing competitiveness in major export items to China, as shown by shrinking market shares.

Korean products’ market share among imports in China rose sharply after the establishment of diplomatic ties in 1992, but began to slide from its peak of 11.6 percent in 2005.

China’s dependence on Korea’s key industries such as petrochemicals, semiconductors and cars is falling, casting shadows on the Korean economy. The country’s dependence on Korean high-tech goods such as IT-related components and machinery parts, on the other hand, has grown.

But even this is likely to drop with the global economic slowdown, according to Chung.

“Exports of Chinese companies that assemble and process IT or electronic gadgets in cooperation with Korean firms are declining due to the sluggish world economy,” Chung said.

“Korea’s trade surplus with China has started to shrink.”

Korea’s exports to China surged 22.9 percent on annual average over the past 20 years, more than double the average growth of Korea’s total exports at 11 percent.

Steel sheets were the biggest export item in 1992, followed by synthetic resins, iron bars and leather.

They are now replaced by flat screen displays, semiconductors, petroleum products and auto parts.

As for investment, Korea’s investment in China continued to decline from 2007 as it invested more through Hong Kong after the Closer Economic Partnership Arrangement between mainland China and Hong Kong took effect in 2004.

Despite the massive investment from Korea to China, the two only recently inked an agreement, a tripartite deal with Japan, to treat investors from each other’s country equally as locals.

The three countries in May signed an investment guarantee treaty that calls for providing most-favored-nation status and other protective measures for investment from each other.

Evolving economic relationship

The division of labor, in which Korea exported intermediary goods to China for labor-intensive industrial processing and the final goods were exported from China to global markets, helped both export-driven economies grow.

The division of labor between China and East Asian industrial nations helped expand the trade imbalance between China and the U.S., which was counted as one of the factors that led to the global financial crisis in 2008.

“With Korea and China standing on the same side of the global trade imbalance, Korea never joined the U.S. or the European Union in pressuring China to appreciate the yuan. Rather, Seoul saw any signs of the yuan’s appreciation as a major risk to the Korean economy and sought to prepare against it,” said Jie Man-soo, professor at Dong-A University.

“This shows that the economic companionship Korea and China have built so far has reached a level in which they share similar interests and positions on key issues of international trade.”

Bilaterally, the two have had their share of disputes over intellectual property, corporate investment and trade such as the one over garlic in the late 1990s.

But in terms of regional integration, Seoul and Beijing have shown a high level of cooperation, especially in finance.

The first successful step toward regional economic cooperation in East Asia was the Chiang Mai Initiative for international currency swaps, which followed the 1997-98 crisis.

Korea and China played key roles in expanding the Chiang Mai initiative fund into a multilateral fund in 2010 from what was a web of bilateral currency swap agreements.

Korea, China, Japan and 10 Southeast Asian countries, or the ASEAN Plus Three group, agreed earlier this year to double the size of the Chiang Mai Initiative Multilateralization fund to $240 billion, at Seoul’s proposal, to better absorb shocks from possible crises in Europe.

The elevated status of the two countries in the world economy, however, will make it harder for Korea to directly pursue its interests in its relationship with China, Jie said, adding that Seoul will have to do it in the context of a multilateral framework through cooperation with advanced nations.

By Kim So-hyun (sophie@heraldcorp.com)

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[Herald Interview] 'Amid aging population, Korea to invite more young professionals from overseas'](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/24/20240424050844_0.jpg&u=20240424200058)

![[KH Explains] Korean shipbuilding stocks rally: Real growth or bubble?](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/25/20240425050656_0.jpg&u=)