Minister avows onset of unification preparations, calls for dialogue with North Korea

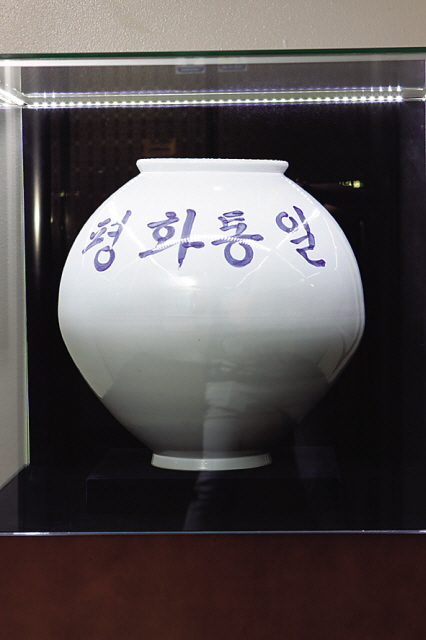

White porcelain ceramics represent the epitome of Korea’s traditional aesthetics ― steeped in simplicity, purity and harmony with nature.

The moon jar, dating back to the 17th and 18th centuries, is the most prized of its kind. Its exact symmetry, round shape and milky white hue are reminiscent of a full moon and characterize fertility and a good harvest.

Due to their large size, the upper and lower parts of the jars are made separately and joined later. Sophisticated skills are needed to make the join seamless and maintain the perfect form.

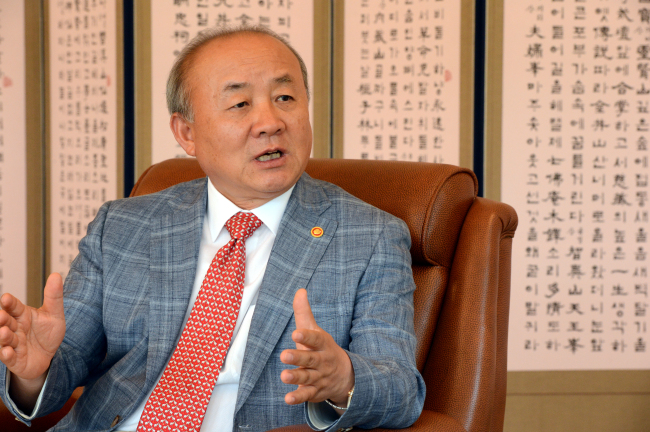

Unification Minister Yu Woo-ik was attracted by the Moon jar’s symbolism when he was trying to choose an icon for his campaign aimed at boosting public awareness on preparing for the two Koreas’ reunification.

“The two halves are put together to form one jar as the two Koreas should eventually be,” the minister said.

White porcelain ceramics represent the epitome of Korea’s traditional aesthetics ― steeped in simplicity, purity and harmony with nature.

The moon jar, dating back to the 17th and 18th centuries, is the most prized of its kind. Its exact symmetry, round shape and milky white hue are reminiscent of a full moon and characterize fertility and a good harvest.

Due to their large size, the upper and lower parts of the jars are made separately and joined later. Sophisticated skills are needed to make the join seamless and maintain the perfect form.

Unification Minister Yu Woo-ik was attracted by the Moon jar’s symbolism when he was trying to choose an icon for his campaign aimed at boosting public awareness on preparing for the two Koreas’ reunification.

“The two halves are put together to form one jar as the two Koreas should eventually be,” the minister said.

Using the Moon jars as a model, the ministry recently launched the so-called Unification Jar to drum up public donations to prepare for a future fiscal shock of incorporating with the destitute North.

“Through the jars, I want to announce at home and abroad that the Korean government and people have begun preparing for a peaceful unification, which will never be a burden to neighbor countries but contribute to their livelihoods, the peace of the world and the advancement of civilization,” he said.

Reunification has been a cherished dream among Korean people and a foremost goal enshrined in the country’s constitution.

However, the debate on reunification is an inevitably contentious one. Many South Koreans are wary of the potentially immense costs and disorder. North Korea fears it would mean the demise of its iron-fisted regime and absorption into its affluent neighbor.

Yu has been striving to convince Koreans why they need to prepare for the seemingly distant event. Despite strained cross-border ties amid Pyongyang’s recent series of provocations, now is the “right time” to get started, he said.

“The world order is on the cusp of a sea change. If you miss the timing, you can’t put back the clock,” Yu told The Korea Herald, citing the global financial crisis and democratization in the Middle East.

“North Korea is helplessly suffering from serious economic difficulties and international isolation. But the South, with its unprecedented national power, cannot face away the most pressing task of its own ― unification.”

Since he took office in September, the minister has given more than 30 lectures on the need for reunification and fundraising to students, public servants and civic groups throughout the country, while meeting officials from other governments and international agencies in search of their support.

Over the last couple of months, Yu participated in the making and firing of six white porcelain vessels at a ceramic workshop in Mungyeong, North Gyeongsang Province. He handwrote himself “peaceful unification” in Korean on the jars with the help of renowned potter Kim Jeong-ok.

“As the jars grow full, we will consolidate confidence in ourselves, deliver hope to North Koreans and show off our resolve to other countries such as China, Japan and Russia,” Yu said, citing South Koreans’ voluntary gold donation drive at the height of the 1997 Asian financial crisis.

“The signaling effect will not only bring forward unification but also be the motor for a peaceful one.”

A ministry-commissioned study released in August put unification costs at between 55 trillion won and 249 trillion won ($48 billion to $217 billion). The upper end of that range is about one-fifth of the South’s 2011 gross domestic product. That is based on a 2030 price trajectory, assuming that it takes place within the next 20 years and is a peaceful transition.

The ministry, which handles inter-Korean affairs such as humanitarian aid and the Gaeseong Industrial Complex, aims to collect up to 50 trillion won by 2030 under the South-North Cooperation Fund.

Individual Koreans at home and abroad are allowed to make contributions to the fund. The government also plans to earmark money from budget surpluses and other areas.

One of the jars is placed at the agency’s headquarters in Seoul and another was delivered on Monday to President Lee at Cheong Wa Dae, who offered to donate his monthly salary. The minister said he reserved one jar for North Korean people and plans to distribute the remainder based on the public’s needs and attention.

Bankrolling integration is part of Yu’s five-pronged unification policy, along with enhancing public understanding via education, harnessing diplomacy, taking good care of North Korean defectors and establishing an administrative framework.

“It is true that unification will prove expensive in light of Germany’s precedent, but the ongoing discussions tend to overstress money,” Yu said.

In fact, unification cost is another word for investment, he said. Businesses will carve out a new market and find a growth driver by transforming the antiquated North Korean economy, beyond offsetting the “division costs.”

“We’re already shouldering enormous expenses for the current division but we’re so used to the situation that we don’t even know it. There are military and security expenditures, extra transportation charges while making a detour to reach the continent, losses from the economy of smaller scale and, more importantly, costs incurred by social and psychological conflicts ― it’s the root-cause of the Korea discount.”

Yet Yu’s five-pronged strategy is short of stronger pan-government resolve, critics say, due to Lee Myung-bak’s hardline stance toward the North and aloofness from unification.

The unification jars came as a retreat from Lee’s ill-conceived earlier proposal for a unification tax, marking a striking gap between the two confidants in terms of views toward North Korean policy.

While the minister asks Koreans to prepare for reunification, the outgoing president clings to the position that Pyongyang should first apologize for its hostile acts and follow through with its denuclearization pledges before reconciliation.

“We may be doing it later on (after the December presidential vote), but it’s also our job to make efforts for the next government to take over inter-Korean affairs and unification policies in a better condition,” Yu said.

His crusade hit another snag when a relevant bill was scrapped last year amid partisan bickering. Opposition lawmakers branded it “far-fetched,” saying the government should better utilize the moribund cooperation fund already in place. The ministry recently re-submitted the bill in May.

Yu has also been calling for Seoul’s North Korean policy to be conducted more consistently, regardless of swings in cross-border relations, breaking off the long-standing focus on disarmament and pattern of aid, cooperation, talks and sudden freeze.

“Government policies should not solely count on the other party’s good will,” he said. “We need independent measures for unification preparations to go hand in hand with the current division management. If one side pursues them steadfastly, the other cannot but become serious.”

Seoul severed its state-level assistance and personnel exchanges with the North after a South Korean tourist was shot to death at the North Korean Mount Geumgang resort in July 2008. Relations further soured following the sinking of a warship and artillery shelling of a South Korean border island in the West Sea in 2010, which claimed nearly 50 lives. The military-focused regime denies responsibility.

Tensions linger on the peninsula six months after young leader Kim Jong-un took power after the death of his late father and longtime despot, Jong-il. The bellicose regime has continued its saber-rattling and verbal attacks with an increasingly hostile tone toward Lee, Yu, the Seoul government and conservative media outlets here.

With the nascent leadership boasting considerable durability, conflicting signs of changes have emerged in recent months from the reclusive state.

Speculation is rising that the young, Swiss-educated leader may moderately open up his country to perk up the poverty-stricken economy and forestall any signs of destabilization. Economic revitalization is also a crucial element to realize his vision of an “ideologically and militarily strong nation,” experts say.

By Shin Hyon-hee (heeshin@heraldcorp.com)

![[Graphic News] More Koreans say they plan long-distance trips this year](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/17/20240417050828_0.gif&u=)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240419100350)

![[From the Scene] Monks, Buddhists hail return of remains of Buddhas](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050617_0.jpg&u=20240419175937)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240419100350)

![[Today’s K-pop] Illit drops debut single remix](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050612_0.jpg&u=)