Scientists may have found autism indicator in infants’ brains

By Korea HeraldPublished : April 26, 2012 - 17:58

SEATTLE ― It was a clue ― the kind of clue medical researchers notice.

Intent on finding answers about autism, now estimated to affect 1 of every 88 children, they followed it, poking and prodding and scanning, prying open its secrets.

It was a curious little observation that, for any individual child, didn’t mean much. But over time, measurements from hundreds of children suggested an intriguing trait: As a group, preschoolers diagnosed with autism tended to have larger heads.

That meant something was going on with their brains. But what?

The clue, pursued with the help of MRI scans that peered into sleeping babies’ brains, led researchers to a stunning discovery: Long before symptoms appeared, 6-month-old babies ― who were much later diagnosed with autism ― already had marked differences in their brains’ “wiring,” the white matter that connects different regions.

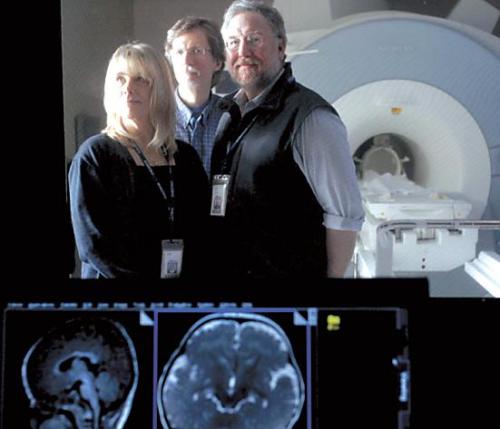

To Dr. Stephen Dager, a principal investigator for the University of Washington arm of the multisite Infant Brain Imaging Study, the finding was a shock. Researchers began the scans at 6 months only because they wanted a baseline.

Intent on finding answers about autism, now estimated to affect 1 of every 88 children, they followed it, poking and prodding and scanning, prying open its secrets.

It was a curious little observation that, for any individual child, didn’t mean much. But over time, measurements from hundreds of children suggested an intriguing trait: As a group, preschoolers diagnosed with autism tended to have larger heads.

That meant something was going on with their brains. But what?

The clue, pursued with the help of MRI scans that peered into sleeping babies’ brains, led researchers to a stunning discovery: Long before symptoms appeared, 6-month-old babies ― who were much later diagnosed with autism ― already had marked differences in their brains’ “wiring,” the white matter that connects different regions.

To Dr. Stephen Dager, a principal investigator for the University of Washington arm of the multisite Infant Brain Imaging Study, the finding was a shock. Researchers began the scans at 6 months only because they wanted a baseline.

What they found, almost by accident, appears to be the earliest biomarker for autism.

“Who knew you could see a difference at 6 months of age?” said Dr. Evan Eichler, a UW professor of genome sciences and autism researcher not involved in the brain study. “That tells us something really important.”

Like other scientists focused on autism, the UW researchers are eager to find ways to diagnose the disorder much earlier so children held captive by autism’s often-devastating symptoms can get help coping in the world.

“If these subtle early brain-wiring findings hold up, then it may help us understand the mechanism and the parts of the brain that are implicated, and areas of potential weakness to target with intervention,” said Dager, a UW professor of radiology.

At this point, intervention primarily means behavioral therapy. The earlier it begins, the more likely it is to alter autism’s grip on a child, said Annette Estes, a clinical psychologist and co-principal investigator for the UW site of the study, published recently in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

Ultimately, though, what everyone wants ― particularly now that “personalized medicine” has begun to create gene-specific drugs ― is to put an end to autism. The disorder can rob children of social and communication skills, leaving them to shun contact and lock themselves into rigid, repetitive behaviors.

There’s no blood, genetics or physical test ― including measuring an individual child’s head ― that can predict or diagnose autism. Instead, diagnosis depends on a set of behavioral differences, in the early years often so subtle that they’re missed.

“All we know about autism diagnosis, right now, are the symptoms that are expressed,” Dager said.

Like polio in the early stages, he said, the only help currently available to children with autism is the equivalent of the iron lung ― treating symptoms, but not the underlying disorder.

Now, as scientists did with polio, “we’re trying to go back, to understand the why.”

That quest has gained greater traction in the past few years, thanks to technological advances in imaging and genetics, an influx of funding from private foundations and the willingness of thousands of families to participate.

From genetics to a mother’s metabolism during pregnancy, findings are pouring in from far-flung corners of the research world.

Most scientists believe this neurodevelopmental disorder results from genes, environment and “a kind of luck of the draw,” Dager said.

“It’s a mysterious disorder, so there’s been a lot of effort trying to understand it.”

For their study, Dager, Estes and a host of other researchers zeroed in on the brains of children statistically at higher risk of autism because they have a sibling who already had been diagnosed.

Other studies, said the study’s senior author, Dr. Joseph Piven at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, looked at children only after diagnosis, and never followed children over time, as this one does.

“You can’t just study them at one point in time,” he said. “(Autism) is an unfolding of a condition, both in terms of behavior and of brain.”

To set up the study, the first of its kind, the researchers had to painstakingly calibrate the imaging machines at many different sites, because tiny inconsistencies could obscure or render meaningless the subtle differences they were looking for.

In Seattle, the scans took place at night at Seattle Children’s, where researchers depended on parents, some of whom flew in from distant states, to coax babies to snooze in the giant MRI tube.

What exactly did Dager and his colleagues see when they peered into those baby brains? Immediately, nothing discernible.

But later, after all the scans were sliced and diced and analyzed, researchers looking at results from 6-month scans found differences between babies who demonstrated autism symptoms at 24 months and those who did not.

The differences in those 6-month scans involved the babies’ “white-matter fiber tract development” ― the wiring connecting regions of their brains.

“The early nature of these brain changes was really surprising,” Estes said.

So far, the evidence discovered with this type of MRI, called diffusion tensor imaging, or DTI, points not to just one region of the brain, but to a whole-brain problem, Dager said.

The findings, he cautions, are preliminary. The researchers’ report covered only about a quarter of the 400 higher-risk babies the four-site study is close to enrolling. They’ve applied for funding to continue the study for another five years and to start the scans at 3 months.

Researchers are careful to note they can’t diagnose an individual 6-month-old from a brain MRI. However, “this suggests that perhaps in the future we will be able to do that,” Estes adds.

“There’s real excitement about this,” she said, in part because it helps reassure distraught parents that their parenting didn’t cause autism. “This is already present at 6 months of age.”

Amy Schley was pregnant with Alexis when she saw a flier for Dager’s study at a doctor’s office.

She and her husband, Brian, were concerned because their older daughter had been diagnosed with autism about two years earlier.

When Alexis was 1 month old, the couple signed up for the study.

“I ended up doing it because it would help them figure out what causes autism,” Amy Schley said. “Every parent has probably spent hours on the Internet searching for causes or cures or anything that would help their kid with autism.”

About 85 percent of the babies are able to fall asleep in the MRI scanner, Estes said. That wasn’t true for Baby Alexis.

Alexis missed the 6-month scan because of reflux problems. At 12 months, Schley brought her in, gently bedding her down in the MRI tube. Four hours later, she was still awake, and squirmy. Strike two.

But Schley, now 36, said she’ll stick with the study, and will bring Alexis in again at 24 months.

Knowing Alexis would be evaluated by Estes and other behavioral experts as part of the study, she said, was reassuring. “We would catch the problem early if there was one.”

That didn’t happen with Alexis’ older sister.

“I think back; she had signs at 6 months old, but I didn’t know,” Schley said.

The doctor asked if their baby looked at them. Schley said she did. But now, with Alexis as a comparison, she realizes it wasn’t really at them. “It was more like she was looking through us.”

She babbled, as babies are supposed to do. But not at her parents.

When she played with a toy, she didn’t turn to check in with her parents.

Balance and motor skills lagged. If she climbed a few stairs, she’d panic, unable to get down.

She didn’t process stimulation well and would often scream in public.

Schley and her husband, first-time parents, didn’t add up the clues.

“The first kid, you don’t know. It’s such a subtle difference,” she said. “I didn’t really know until I had a normal kid to compare it to.”

Throughout those years, Schley and her husband fended off criticism from people who accused them of parenting mistakes. They cringed and coped when their daughter screamed and had fits in public.

When she was about 18 months, just staring at them instead of saying “No!” like her peers, her parents sought help. At about 3, she was diagnosed.

Meanwhile, Amy and Brian juggled jobs and day care and fought with insurance, which balked at paying for therapy for social skills. Schley’s father began paying the bills for behavioral therapy, about $1,200 a month.

“It was hard for us,” Schley recalls.

Many parents were hoping genetics researchers would find a single “autism gene.”

So it was with mixed emotions they greeted a trio of studies published in the journal Nature this month, one authored by the UW’s Eichler, reporting that researchers studying more than 600 families with one child with autism had found mutations in hundreds of different genes ― possibly in as many as a thousand.

Most weren’t “random genes,” Eichler said, but were associated with early brain development. And while autism can run in families, in some cases these were new mutations, unique to the child.

The researchers also found that fathers were more likely than mothers to transmit tiny genetic glitches to offspring, and that risk increased with the father’s age.

Other researchers are targeting metabolism as a possible factor. A study recently published in Pediatrics reported that mothers who are obese or who have diabetes are more likely to have a child with developmental delays, including autism.

Vaccines, shunned by some wary parents, have been investigated repeatedly, and researchers have found no link with autism.

“We believe the vaccine thing has been totally disproven,” said Eichler, who has a niece with autism. But like others, he’s resigned to differing opinions. “I even have arguments with my own mother.”

The controversy’s one positive effect, said Dr. Wendy Stone, director of the UW Autism Center, has been to highlight the importance of environmental factors ― “What kinds of things are we eating and touching and walking by that might affect brain development?”

Controversy also has dogged a statistic regarding the prevalence of autism, recently released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention ― up an astounding 78 percent over the past decade. The jury’s still out on the central question: Is autism occurring more frequently, or simply being diagnosed more often?

Such questions may help explain why, after decades of work and at least $1 billion spent in the past 10 years alone, science has no neat answer about autism’s cause, much less a cure.

And while you’d think that might leave researchers discouraged, in fact, just the opposite seems to be true.

“We’re narrowing down on both the causes of autism and the mechanisms,” Piven crows.

“I think autism is in fact many different diseases, just like cancer is,” with both genetic and environmental causes, Eichler says.

The work on genetics will help “crack the case open” on the environmental triggers, says Eichler, who has been working on autism for more than 20 years. “I feel like we’re really there.”

Trials under way are testing drugs targeted at some of autism’s brain-chemistry problems, he notes. “If you can even make a kid somewhat more functional or independent, I could die a happy man.”

Dager, who has been after autism for 15 years, says he and his fellow researchers are encouraged by recent progress. Little by little, they’re refining their questions and ― finally ― getting some answers.

“Nothing is as fast as we’d like it to be, but think how long it took with polio,” he says. “This research we’re doing is just the tip of the iceberg. ... I wouldn’t want to be doing anything else.”

By Carol M. Ostrom

(The Seattle Times)

(MCT Information Services)

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[Graphic News] More Koreans say they plan long-distance trips this year](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/17/20240417050828_0.gif&u=)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240419100350)

![[From the Scene] Monks, Buddhists hail return of remains of Buddhas](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050617_0.jpg&u=20240419175937)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240419100350)

![[Today’s K-pop] Illit drops debut single remix](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050612_0.jpg&u=)