Last week a Korean man living in Oakland, California, shot and killed seven people. The man had moved to America and was pursuing his dream of becoming a nurse. When that dream fell short amid rumors of ill treatment, he took out his frustrations on his classmates and teachers.

A month earlier, in February of this year, in the city of Atlanta, Georgia, another Korean man shot and killed four of his relatives before committing suicide. In his case there were reports of family discord that allegedly led to the attack.

Five years ago another Korean man studying at a university in Virginia went on an extended killing spree ending the lives of 32 innocent people before turning his gun on himself. This act was the deadliest shooting incident in American history by a single gunman. After the tragedy it was revealed that the young man had a long history of mental illness and a persecution complex.

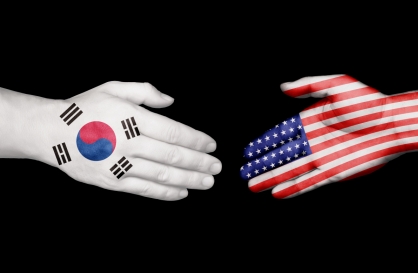

Despite these horrific acts being committed by individuals born and raised in South Korea, many South Koreans attribute these events to America’s fascination with violence and guns; but this is too simple of an excuse.

Recently in South Korea a young woman killed herself after allegedly being insulted by a judge during a trial against her rapist. In her suicide letter she expressed her frustrations with the judicial system and an inability to receive justice. In response the judge, recognizing either his error or her sacrifice, increased the prison sentence of the convicted rapist.

In 2009 former President Roh Moo-hyun killed himself by jumping off of a cliff. His death spared his family and his followers the consequences of a pending investigation and a potential court trial for suspected corruption. Many of his followers honored his sacrifice while expressing frustration with the investigation and accusing the current administration of, figuratively, pushing him to his death.

In an odd twist, President Roh had been previously accused of causing a leading business executive to jump to his death from a bridge over the Han River in Seoul.

These deaths were but a small portion of a long list of South Korean celebrities, politicians and business luminaries who have taken their own lives in recent years. The impact of these high profile suicides can be seen in South Korea’s overall suicide rate which is now the highest among the organization of economically developed countries, having surpassed Japan in 2011. Suicide is also the leading cause of death for South Koreans under the age of 40.

The high incidence of suicide in South Korea is often attributed to a cultural willingness to sacrifice oneself in order to avoid shame for one’s family. The act restores lost honor to the deceased and to his or her family.

But this willingness to kill oneself also reflects an underlying lack of respect for life in general. As renowned psychologist Carl Jung stated, “[we] ought to realize that suicide is murder, since after suicide there remains a corpse exactly as with any ordinary murder.”

Thus the murder rate in South Korea, which is only slightly lower than the murder rate in America without including suicide, jumps to double that of America when suicide is viewed as murder. This fact combined with the all too frequent murder-suicides by South Koreans living in America suggests that when South Korea’s culture of self-sacrifice, as reflected in suicide, moves to a country where guns are easily obtained it becomes a culture of killing. To address this issue South Koreans should look inward to consider what aspects of their society may contribute to these tragedies.

Thus a recent study by a leading medical research hospital looking at the impact of early childhood experiences on brain development may be a starting point for such an analysis. In this study children between the ages of three and six were observed interacting with their mothers. The observers rated the mothers on their nurturing ability. Four years later the children were given brain scans that revealed the hippocampus in children with nurturing mothers was 10 percent larger than their peers who had non-nurturing mothers.

This is significant because the hippocampus is the region of the brain responsible for memory, learning and stress response. Further, numerous studies have shown that children with larger hippocampi (there are two of them, one on each side of your brain) perform better at school and score better on tests of cognitive abilities. And both adults and children suffering from depression have smaller hippocampi than normal individuals.

Applying these principles to the excessive emphasis on after school education in South Korea leads to some startling possibilities. In this country children of elementary school age and younger spend a large portion of their early childhood in playrooms, study rooms and academies away from the nurturing love of their parents. Regardless of the quality of the teachers, the impact of this separation cannot be underestimated.

The irony is that the more time young children are separated from their parents while studying late into the evening the more their school performance and academic abilities may be damaged. A further impact of such educational rigor may be increased depression and an increased likelihood of suicide and, perhaps, in the right environment, murder.

With South Korea’s current low birth rate the country can ill afford to lead the OECD in suicides. Neither can the country afford to develop an international reputation as a breeding ground for murderers.

Perhaps the shock and shame of the latest tragic murder spree by a South Korean in America will induce South Korea as a country to consider whether it is best for children to spend their early childhood years away from the nurturing care of their parents.

While some education offices have recently begun enforcing rules against academies open after 10 o’clock at night, this effort has been focused primarily on high school students. The government should expand this effort nationwide and prohibit children of elementary age or younger from being in playrooms, study rooms or academies after six o’clock in the evening. There are few workers who must legitimately be at work past this hour and even fewer households where both parents must come home after this hour.

Finally when academies try to move their study sessions online, the government should enact the same type of restrictions as have been enacted to prevent online gaming late at night. And while some may argue that this is burdensome for parents, the future of South Korea that is contained within its children is at stake.

By Daniel Fiedler

Daniel Fiedler is a professor of law at Wonkwang University. He also holds an honorary position as an international legal advisor to the North Jeolla Provincial Government. ― Ed.

A month earlier, in February of this year, in the city of Atlanta, Georgia, another Korean man shot and killed four of his relatives before committing suicide. In his case there were reports of family discord that allegedly led to the attack.

Five years ago another Korean man studying at a university in Virginia went on an extended killing spree ending the lives of 32 innocent people before turning his gun on himself. This act was the deadliest shooting incident in American history by a single gunman. After the tragedy it was revealed that the young man had a long history of mental illness and a persecution complex.

Despite these horrific acts being committed by individuals born and raised in South Korea, many South Koreans attribute these events to America’s fascination with violence and guns; but this is too simple of an excuse.

Recently in South Korea a young woman killed herself after allegedly being insulted by a judge during a trial against her rapist. In her suicide letter she expressed her frustrations with the judicial system and an inability to receive justice. In response the judge, recognizing either his error or her sacrifice, increased the prison sentence of the convicted rapist.

In 2009 former President Roh Moo-hyun killed himself by jumping off of a cliff. His death spared his family and his followers the consequences of a pending investigation and a potential court trial for suspected corruption. Many of his followers honored his sacrifice while expressing frustration with the investigation and accusing the current administration of, figuratively, pushing him to his death.

In an odd twist, President Roh had been previously accused of causing a leading business executive to jump to his death from a bridge over the Han River in Seoul.

These deaths were but a small portion of a long list of South Korean celebrities, politicians and business luminaries who have taken their own lives in recent years. The impact of these high profile suicides can be seen in South Korea’s overall suicide rate which is now the highest among the organization of economically developed countries, having surpassed Japan in 2011. Suicide is also the leading cause of death for South Koreans under the age of 40.

The high incidence of suicide in South Korea is often attributed to a cultural willingness to sacrifice oneself in order to avoid shame for one’s family. The act restores lost honor to the deceased and to his or her family.

But this willingness to kill oneself also reflects an underlying lack of respect for life in general. As renowned psychologist Carl Jung stated, “[we] ought to realize that suicide is murder, since after suicide there remains a corpse exactly as with any ordinary murder.”

Thus the murder rate in South Korea, which is only slightly lower than the murder rate in America without including suicide, jumps to double that of America when suicide is viewed as murder. This fact combined with the all too frequent murder-suicides by South Koreans living in America suggests that when South Korea’s culture of self-sacrifice, as reflected in suicide, moves to a country where guns are easily obtained it becomes a culture of killing. To address this issue South Koreans should look inward to consider what aspects of their society may contribute to these tragedies.

Thus a recent study by a leading medical research hospital looking at the impact of early childhood experiences on brain development may be a starting point for such an analysis. In this study children between the ages of three and six were observed interacting with their mothers. The observers rated the mothers on their nurturing ability. Four years later the children were given brain scans that revealed the hippocampus in children with nurturing mothers was 10 percent larger than their peers who had non-nurturing mothers.

This is significant because the hippocampus is the region of the brain responsible for memory, learning and stress response. Further, numerous studies have shown that children with larger hippocampi (there are two of them, one on each side of your brain) perform better at school and score better on tests of cognitive abilities. And both adults and children suffering from depression have smaller hippocampi than normal individuals.

Applying these principles to the excessive emphasis on after school education in South Korea leads to some startling possibilities. In this country children of elementary school age and younger spend a large portion of their early childhood in playrooms, study rooms and academies away from the nurturing love of their parents. Regardless of the quality of the teachers, the impact of this separation cannot be underestimated.

The irony is that the more time young children are separated from their parents while studying late into the evening the more their school performance and academic abilities may be damaged. A further impact of such educational rigor may be increased depression and an increased likelihood of suicide and, perhaps, in the right environment, murder.

With South Korea’s current low birth rate the country can ill afford to lead the OECD in suicides. Neither can the country afford to develop an international reputation as a breeding ground for murderers.

Perhaps the shock and shame of the latest tragic murder spree by a South Korean in America will induce South Korea as a country to consider whether it is best for children to spend their early childhood years away from the nurturing care of their parents.

While some education offices have recently begun enforcing rules against academies open after 10 o’clock at night, this effort has been focused primarily on high school students. The government should expand this effort nationwide and prohibit children of elementary age or younger from being in playrooms, study rooms or academies after six o’clock in the evening. There are few workers who must legitimately be at work past this hour and even fewer households where both parents must come home after this hour.

Finally when academies try to move their study sessions online, the government should enact the same type of restrictions as have been enacted to prevent online gaming late at night. And while some may argue that this is burdensome for parents, the future of South Korea that is contained within its children is at stake.

By Daniel Fiedler

Daniel Fiedler is a professor of law at Wonkwang University. He also holds an honorary position as an international legal advisor to the North Jeolla Provincial Government. ― Ed.

![[AtoZ into Korean mind] Humor in Korea: Navigating the line between what's funny and not](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/22/20240422050642_0.jpg&u=)

![[Herald Interview] Why Toss invited hackers to penetrate its system](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/22/20240422050569_0.jpg&u=20240422150649)

![[Graphic News] 77% of young Koreans still financially dependent](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/22/20240422050762_0.gif&u=)

![[Exclusive] Korean military to ban iPhones over security issues](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050599_0.jpg&u=)