With many cases causing public outrage ...

Is punishment for sex crime too lenient?

Scales of justice

A series of high-profile sex crime cases in recent years has caused public uproar over perceived leniency in sentencing. Perhaps most controversial of all was the punishment doled out to three teachers at Gwangju Inhwa School for sex crimes against deaf students. Two teachers were sentenced to six months and two years in prison for sexual assault, while the principal received a suspended sentence of two and a half years for the rape of a student. After public outrage was rekindled with the release of a movie, “The Crucible,” based on the events of the case, the National Assembly passed legislation to toughen laws against sexual assault. Among other provisions, the new laws did away with the statute of limitations for sex crimes against minors under 13 and disabled women, and increased the maximum penalty to life imprisonment.

Last year, the National Assembly scrapped a provision that had required the complaint of a victim before a child sex offender could be prosecuted. The balance between offenders’ rights, those of their victims and society’s desire for justice is unlikely to be struck without friction. Last year, in a large sample of district court cases of sexual assault, that balance saw 24 percent of sex offenders receive a prison sentence, 33 percent a suspended sentence and 14.3 percent a fine.

Rapists can receive as little as 0-3 years

About 10 years ago I worked with a celebrated Korean-American professor in Michigan. Dr. Kim had moved to the United States long ago after completing his law studies in Korea.

I once asked this professor what the biggest difference was that he noticed when he came to the United States. I expected him to say, “I really missed kimchi” or “the smell of cheese made me gag” or perhaps he would relay some funny story about a miscommunication due to a cultural difference. I could never have guessed his answer: “The value of a human life.”

He explained how he noticed that everyone’s life seemed to have great value in the U.S., regardless of age, sex, education or economic status. Even the beggar was precious and the law protected this value.

One look at the differences between the average sentence for rape in the U.S. and in Korea seems to support Dr. Kim’s impression. Although sentences for rape vary between state and federal jurisdictions, criminals convicted of rape in the U.S. are typically sentenced to terms 9-22 years longer than a rape sentence in Korea, where perpetrators have served as little as 0-3 years (even when the victim was a child).

States like Florida have imposed mandatory minimums that start at 10 years for rape and 25 years when the victim is a child. According to the U.S. National Conference of State Legislatures, at least 25 states in the U.S. have enacted mandatory 25-year minimum sentences for first-time child sex crime offenders and at least 39 have enacted GPS or electronic monitoring provisions specific to sex offenders.

Not only are the sentences shorter in Korea for the same crime but some see a correlation between the length of the sentence imposed and the social or economic status of the victim. Increasing penalties for rape and setting mandatory minimum limits protects the inherent value of the people in Korea.

Criminal sanctions have several goals: punish the wrongdoer; pay a debt to society; protect society; and, ideally, rehabilitate the wrongdoer and deter future crime.

Unlike civil actions, which seek to compensate the victim for their losses, in criminal cases the plaintiff is the people ― society at large. The punishment is in part retribution ― a debt owed for the injury caused to society.

In a sense, we are all the victim of any rape, as it damages the security and well-being of our community. How do we value our security and the dignity of the community? What is the loss when it is violently breached? This is the cost we should assert as victims at large ― and the debt to society that criminal law should factor into a sentence.

I am not in favor of mandatory sentencing in every situation. But when the crime is as serious as rape, there needs to be a minimum that reflects the value we place on life, dignity and safety.

Are we worth as little as 0-3 years of the perpetrator’s time for a violent act that has life-long consequences for the victim? Are we not owed a greater term of security knowing the offender is incapable of committing another crime because of his incarceration and electronic monitoring upon release?

Although nobody likes their discretion limited, mandatory minimum sentences for rape may come as an unspoken relief to the judiciary. The decision to take away someone’s freedom is not an easy or pleasant one. Without supportive limits in our law the judge must face this pressure alone in every case.

My sister sometimes limits the discretion her teenage daughter has to make in order to empower her among her peers and help her avoid peer pressure. Although the daughter complains of this lack of freedom, inside we can see the daughter actually appreciates it because it takes the pressure off her.

There is security in having this authority as support for your decision. The judiciary in Korea also needs the support of our laws to give them the backbone needed to make tough decisions in the face of potentially corrupting pressures to shorten the punishment for well-connected criminals.

Perhaps the judiciary needs higher sentencing standards to bring the debt paid by criminals in closer alignment with our inherent self-worth. In any case, the value of a person should not depend on the their socio-economic status. Korea has made great strides in elevating its status on the world stage over the years. They need to continue to move ahead with laws that add value to all people on the domestic stage as well.

Is punishment for sex crime too lenient?

Scales of justice

A series of high-profile sex crime cases in recent years has caused public uproar over perceived leniency in sentencing. Perhaps most controversial of all was the punishment doled out to three teachers at Gwangju Inhwa School for sex crimes against deaf students. Two teachers were sentenced to six months and two years in prison for sexual assault, while the principal received a suspended sentence of two and a half years for the rape of a student. After public outrage was rekindled with the release of a movie, “The Crucible,” based on the events of the case, the National Assembly passed legislation to toughen laws against sexual assault. Among other provisions, the new laws did away with the statute of limitations for sex crimes against minors under 13 and disabled women, and increased the maximum penalty to life imprisonment.

Last year, the National Assembly scrapped a provision that had required the complaint of a victim before a child sex offender could be prosecuted. The balance between offenders’ rights, those of their victims and society’s desire for justice is unlikely to be struck without friction. Last year, in a large sample of district court cases of sexual assault, that balance saw 24 percent of sex offenders receive a prison sentence, 33 percent a suspended sentence and 14.3 percent a fine.

Rapists can receive as little as 0-3 years

About 10 years ago I worked with a celebrated Korean-American professor in Michigan. Dr. Kim had moved to the United States long ago after completing his law studies in Korea.

I once asked this professor what the biggest difference was that he noticed when he came to the United States. I expected him to say, “I really missed kimchi” or “the smell of cheese made me gag” or perhaps he would relay some funny story about a miscommunication due to a cultural difference. I could never have guessed his answer: “The value of a human life.”

He explained how he noticed that everyone’s life seemed to have great value in the U.S., regardless of age, sex, education or economic status. Even the beggar was precious and the law protected this value.

One look at the differences between the average sentence for rape in the U.S. and in Korea seems to support Dr. Kim’s impression. Although sentences for rape vary between state and federal jurisdictions, criminals convicted of rape in the U.S. are typically sentenced to terms 9-22 years longer than a rape sentence in Korea, where perpetrators have served as little as 0-3 years (even when the victim was a child).

States like Florida have imposed mandatory minimums that start at 10 years for rape and 25 years when the victim is a child. According to the U.S. National Conference of State Legislatures, at least 25 states in the U.S. have enacted mandatory 25-year minimum sentences for first-time child sex crime offenders and at least 39 have enacted GPS or electronic monitoring provisions specific to sex offenders.

Not only are the sentences shorter in Korea for the same crime but some see a correlation between the length of the sentence imposed and the social or economic status of the victim. Increasing penalties for rape and setting mandatory minimum limits protects the inherent value of the people in Korea.

Criminal sanctions have several goals: punish the wrongdoer; pay a debt to society; protect society; and, ideally, rehabilitate the wrongdoer and deter future crime.

Unlike civil actions, which seek to compensate the victim for their losses, in criminal cases the plaintiff is the people ― society at large. The punishment is in part retribution ― a debt owed for the injury caused to society.

In a sense, we are all the victim of any rape, as it damages the security and well-being of our community. How do we value our security and the dignity of the community? What is the loss when it is violently breached? This is the cost we should assert as victims at large ― and the debt to society that criminal law should factor into a sentence.

I am not in favor of mandatory sentencing in every situation. But when the crime is as serious as rape, there needs to be a minimum that reflects the value we place on life, dignity and safety.

Are we worth as little as 0-3 years of the perpetrator’s time for a violent act that has life-long consequences for the victim? Are we not owed a greater term of security knowing the offender is incapable of committing another crime because of his incarceration and electronic monitoring upon release?

Although nobody likes their discretion limited, mandatory minimum sentences for rape may come as an unspoken relief to the judiciary. The decision to take away someone’s freedom is not an easy or pleasant one. Without supportive limits in our law the judge must face this pressure alone in every case.

My sister sometimes limits the discretion her teenage daughter has to make in order to empower her among her peers and help her avoid peer pressure. Although the daughter complains of this lack of freedom, inside we can see the daughter actually appreciates it because it takes the pressure off her.

There is security in having this authority as support for your decision. The judiciary in Korea also needs the support of our laws to give them the backbone needed to make tough decisions in the face of potentially corrupting pressures to shorten the punishment for well-connected criminals.

Perhaps the judiciary needs higher sentencing standards to bring the debt paid by criminals in closer alignment with our inherent self-worth. In any case, the value of a person should not depend on the their socio-economic status. Korea has made great strides in elevating its status on the world stage over the years. They need to continue to move ahead with laws that add value to all people on the domestic stage as well.

By Colleen Reid

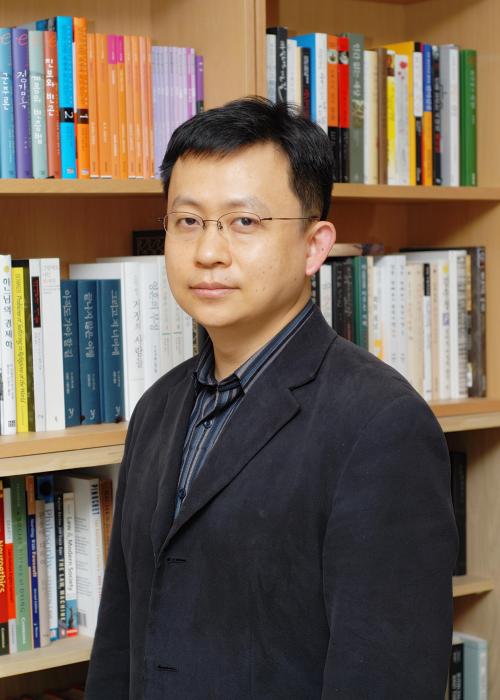

Colleen Ried is a professor of law at Hanyang University School of Law. ― Ed.

The system is tough on sex crimes

Any criminal justice system can be seen as lenient on sex crimes. When people do not recognize the criminal nature of sexual violence, they may misunderstand their criminal justice system as soft on sex crimes. Sexual violence is less reported by the victims than any other form of violence, and much more difficult to secure evidence for and prove guilt to convict and sentence. Criminologists term this the problem of attrition.

Still, some claim that Korean law and policy in punishing sex crimes is too lenient. Firstly, they recognize that current criminal laws do not punish heinous sex offenders severely. Secondly, they see the police and prosecutors as ineffective in persecuting offenders and preventing re-offending. Thirdly, they accuse the criminal court of leniency in sentencing sex offenders.

What should be blamed, however, are poor programs for rehabilitating persistent sex offenders and a chauvinistic culture hostile to female victims, not the criminal law and policy, which sees sex crimes as most heinous and serious.

Most sexual violence, especially crimes against children, is punished severely under current special criminal acts. According to the Act on the Punishment of Sexual Crimes and Protection of Victims of 2011, rape against minor under 13, or an injury by rape or sexual assault, shall be punished by imprisonment of not less than 10 years to life. Rape by a relative, rape against a handicapped person, or sexual assault against a minor under 13 shall be punished by imprisonment of not less than seven years. Under the Act on the Protection of Children against Sexual violence of 2011, the rape of minors under 19 shall be punished by imprisonment of not less than five years. Sexual assault against a minor under 19 shall be punished by imprisonment of not less than three years. Any perpetrator of rape or sexual assault who kills his victim shall be punished by death or imprisonment for life.

Such harshness of punishment is reinforced by special measures which were recently introduced into the Korean criminal justice system: Sex offenders who have completed their criminal sentences must be registered in the sex offender registry, which is made available to the general public via a website. Registered offenders are subject to additional restrictions. Judges may order the electronic tagging of sex offenders for up to 30 years. GPS devices attached to previous offenders locate their whereabouts and report their position back to a probation office. Under the Act on the Chemical Castration of Sex Offenders of 2011, the court may impose a treatment program for dangerous sex offenders for up to 15 years.

According to the National Criminal Justice Statistics of 2010, the conviction rate of rape is 42.7 percent. This is lower than that of the most serious crime, homicide, 68.3 percent, but not lower than the 39.6 percent for robbery, and just below the 45 percent for arson. Of 2,104 cases of rape and sexual assault sentenced at district courts, a life sentence was imposed for five, imprisonment for 537, a suspended sentence for 686 and fine for 308. As for 22,392 cases of assault and battery, imprisonment was imposed for 1,282, a suspended sentence for 2,801 and fine for 13,622. Regarding the terms of imprisonment, more than three years were imposed on 139 convicts of murder, over five years for 157, and over 10 years for 196 ― in 529 cases of rape and sexual assault, 153, 58 and seven received the same sentences. Sentencing of sex crimes, especially crimes against children, has recently been becoming more severe than that for any other violent crime. In 2010, the Sentencing Commission amended its sentencing guidelines on sex crimes to increase both the minimum and maximum term. Now the sentence range of rape is from one year and six months to seven years, and that of rape of minor under 13 is from 6 years to 13 years. The sentencing range for murder is six years to 17 years.

By Han-Kyun Kim

Han-Kyun Kim is a research fellow at Korean Institute of Criminology and a graduate of Korea University and University of Cambridge. ― Ed.

-

Articles by Korea Herald

![[From the Scene] Monks, Buddhists hail return of remains of Buddhas](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050617_0.jpg&u=20240419175937)

![[From the Scene] Monks, Buddhists hail return of remains of Buddhas](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050617_0.jpg&u=20240419175937)

![[KH Explains] Hyundai's full hybrid edge to pay off amid slow transition to pure EVs](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=652&simg=/content/image/2024/04/18/20240418050645_0.jpg&u=20240419100350)

![[Today’s K-pop] Illit drops debut single remix](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=642&simg=/content/image/2024/04/19/20240419050612_0.jpg&u=)