[R&D POLICY IN KOREA (42)] Building global knowledge networks through brain circulation in bio, pharmaceutical industry

By 황장진Published : Feb. 17, 2011 - 20:04

This is the 42nd in a series of articles introducing the Korean government’s R&D policies. Researchers at the Science & Technology Policy Institute will explain Korea’s R&D initiatives aimed at addressing major socioeconomic problems facing the nation. ― Ed.

To bring back and utilize human resources that have gone overseas has been a goal of companies and governments of developing countries for a long time.

This is because these highly skilled human resources, who have world-class ability, can play a very important role in a company’s growth and national development. Therefore, if they remain abroad, their countries will suffer a “brain drain.”

Recently, highly skilled migrants from some developing countries have made vital contributions to the industrial development and economic growth of their homelands. They have built knowledge networks between their home countries and their new countries of residence, which have been increasingly significant in recent knowledge-based economies.

Thus, a “brain circulation” model that takes advantage of human resources abroad to build global knowledge networks has been given attention by most developing countries as a new strategy.

New argonauts

A typical example of this model is shown in the IT industries in Taiwan and India. In Taiwan, skilled workers who were educated or worked in the Silicon Valley returned to their home country, launched IT parts companies in the Hsinchu Science Park and grew these companies fast, supplying their manufactured parts to U.S. assembly companies. The cluster that formed as a result was important to the development of Taiwan’s IT industry. The global network that these workers established played an important role in this process. Consequently, the IT industry in Taiwan was able to enter the international market through the global knowledge networks that these workers were part of, and Silicon Valley’s venture system was transplanted at the same time, boosting Taiwan’s venture ecosystem.

The IT industry in India got its start while supplying simple services such as software coding to advanced countries. Highly skilled engineers who were educated or worked abroad returned to India, improved the level of IT services, and expanded the scope so that it played a fundamental role in creating worldwide software companies in India. IT companies such as Wipro have enhanced the knowledge network with markets in advanced countries through returning skilled workers and have entered the U.S. market.

In addition, some Taiwanese and Indian businessmen set up companies or local offices both in the U.S. and their home countries.

Saxenian (2006) called them the “New Argonauts,” to indicate the skilled workers from developing countries who live abroad and build knowledge networks in various ways between advanced countries and developing countries, which contribute to industrial development in their home country.

The establishment of global knowledge networks by these workers has developed domestic industries and upgraded them to the global level.

Global networks

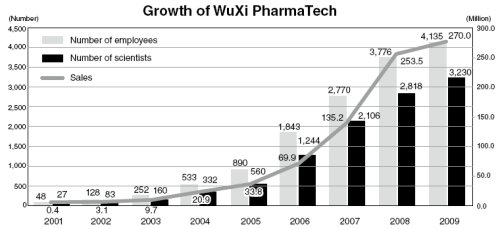

Biotech and pharmaceutical industries recently showed the same phenomenon that Saxenian found in the IT industry. WuXi PharmaTech (WuXi) in China, for example, is a contract research organization (CRO) that supplies the chemicals that are necessary in drug discovery, and it has recently grown rapidly and changed the landscape of the CRO market.

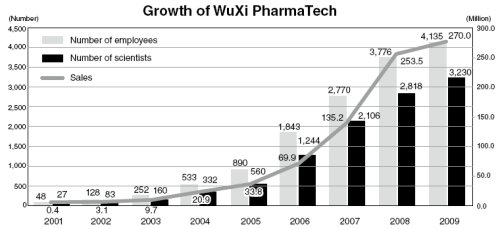

This company continues to grow, almost doubling annually since its establishment in 2000, and it has grown into a large enterprise with 4,135 employees as of the end of 2009 (3,230 research staff) and sales of $270 million (net sales of $5.3 billion).

The reason WuXi was able to achieve rapid growth was due to the capabilities of those familiar with global standards, combined with the capabilities of scientists in China, which made it possible to deliver high quality services at a low price.

WuXi was founded by Dr. Ge Li who received a Ph.D. in organic chemistry from Columbia University and served eight years at Pharmacopeia in the United States. It employs over 100 scientists who were educated and had work experience from the United States.. Knowledge networks created by the scientists who returned home from the U.S. played an important role in the growth of WuXi.

Since the 1980s, global knowledge networks have developed in the pharmaceutical industry. Large pharmaceutical companies in advanced countries faced problems with R&D productivity and they looked externally for sources of innovation. Despite an increase in research funds, fewer new drugs are released every year, and large pharmaceutical companies in advanced countries have tried to reduce their research funds and raise R&D performance by way of outsourcing non-core R&D activities and licensing-in drug candidates from outside. This process has brought venture companies and CROs to supply promising drug candidates.

It is noteworthy that increasing numbers of bio venture companies and CROs in developing countries have become partners with global pharmaceutical companies as their level of science and technology has risen.

In the background of the expanding role of developing countries in the world’s pharmaceutical industries, as shown in the case of WuXi, the transnational knowledge community that has formed between developed countries and developing countries plays a critical role.

Transnational knowledge communities in Korea

In Korea, since 2005, dozens of the leading scientists who worked in the U.S. pharmaceutical industry returned and were recruited as chiefs of research institutes in Korea, and they have had a positive impact. Green Cross, Daewoong Pharmaceutical, ChoongWae Pharmaceutical, and Yuhan Corporation have recruited some of the United States’ leading researchers as R&D chiefs. However, the number of researchers brought in is small compared to China and India, and their impact on the pharmaceutical industry in South Korea is limited.

To investigate any possibility as to whether or not the Korean biotech and pharmaceutical industries can grow by taking advantage of skilled Korean workers abroad, STEPI carried out a survey with Korean scientists who are active in the U.S. biotechnology and pharmaceutical industry. Currently, more than 500 Korean scientists work in the U.S. for companies in the biotechnology and pharmaceutical fields.

They organized Korean associations such as the Korean American Society in Biotech and Pharmaceuticals, the Bay Area Korean-American Scientists Society in Biotechnology and Pharmaceuticals, and the BioPharma Association to exchange information, network, etc. The number of members in these organizations combined is about 700.

Additionally, the Korean Life Scientists in the Bay Area and the New England Bioscience Society are Korean associations that consist mainly of a total of 700 university professors, researchers and students (Table 1). A total of 214 people responded to the survey that was conducted with these associations and 57 of these respondents worked for companies.

In the following table, the opinions of the 57 respondents were analyzed.

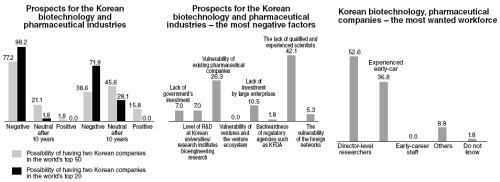

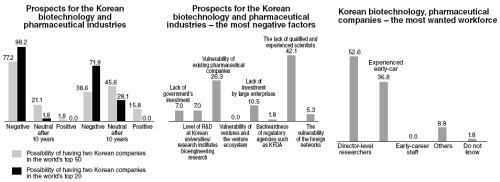

First, when asked about the 10-year outlook for the biotechnology and pharmaceutical industries in Korea, the respondents were very negative. They were less negative on the 20-year outlook and it was thought that the industry would grow slightly. The reasons cited were: negative prospects for the development of Korea’s biotechnology and pharmaceutical industries; lack of experienced workforce, especially director-level research staff.

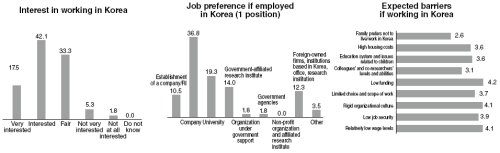

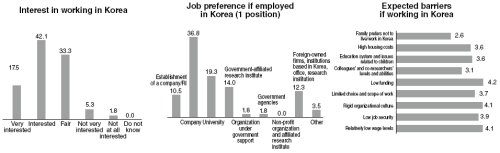

Meanwhile, Respondents were highly interested in getting a job in Korea and showed a strong willingness to work. Sixty percent of the respondents expressed interest in the possibility of working in Korea, and if already employed in Korea, they preferred working in public sector enterprises. However, the expected barriers while working in Korea included low funding levels, the rigid organizational culture of Korea and relatively low wage levels.

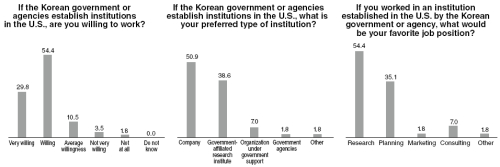

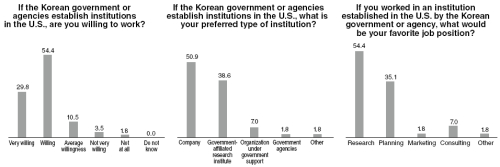

When the Korean government or agencies established local institutions in the United States, the willingness to work was 75 percent ― higher than that of working in Korea. Regarding a preferred employer, most respondents preferred companies and government-affiliated research institutions but respondents who worked in universities and public institutes showed high preferences for government-affiliated research institutions.

For job types, the majority of respondents preferred research work (55 percent), but planning services (35.3 percent) also showed significant numbers.

Looking at how the government supports the network of overseas workers, the respondents preferred the support of overseas Korean professional networks, overseas expansion of Korean firms and entrepreneurship, establishment of overseas offices for biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies, and Korean government participation in R&D industry planning and assessment, while preferences for a plan to attract domestic workers was relatively low. In terms of support for professional societies and associations, sponsors (33.3 percent) or database services for Korean professionals in the United States (28.1 percent) were preferred (see Figure 6).

Building global knowledge networks in Korean biotechnology and pharmaceutical Industries

The measures to establish the global knowledge network can be divided into an “in” strategy that attracts overseas workers and institutions, an “out” strategy to establish a base abroad, and a “bridge” strategy to link the domestic and international networks. Above all, the “in” strategy needs to attract leading overseas research institutes.

The government should coordinate and support plans to attract at least three or four leading overseas research institutes which employ a sizable number of researchers. Currently, except for the Institute of Pasteur Korea, and there have been few foreign research institutes that conduct R&D in Korea.

Local governments are also very interested in attracting renowned research institutes, however, they are likely to have uncertain budgets and no long-term visions for such a strategy. In addition, the international research centers that the government supports need to integrate the advanced systems and advantages of Korea. The government needs to establish a vision and commit to drawing in three or four sizable research institutes, and it should plan a matching fund with local governments.

Second, it is necessary to recruit globally experienced and skilled researchers to work for publicly supported organizations specialized in biotechnology and pharmaceuticals. For example, the New Drug Development Support Center located in the High-Tech Medical Complex that is being established acts as a government institute to support translational research that is necessary for the domestic biotechnology and pharmaceutical industries. The Center needs experienced overseas professionals who have worked at multinational companies and have global contacts.

Third, it is necessary to plan joint R&D projects among Korean venture companies and biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies in advanced countries.

Similar to the Israel-U.S. Binational Industrial Research and Development Foundation program that was established to absorb U.S. capital and market information, a joint R&D program between U.S. companies and Korean institutions (affiliated institutes, and ventures, including corporations) can be developed. Through such a program, companies in advanced countries could be provided an opportunity to conduct R&D more aggressively in Korea and take advantage of Korea as their R&D base.

Based on this network, there should be support to attract investment from advanced countries and also support for Korean professionals who have experience in advanced countries, to establish venture companies using the knowledge networks between Korea and advanced countries.

Fourth, a fund for investments in Korean bio-venture in collaborations with venture capitals in advanced countries should be created. A successful example of such is the Yozma Group in Israel that manages venture capital funds. If Korean ventures attract investment from advanced countries (multinational corporations or venture capital) then Korean fund will match for it. The Korean government should create a “fund of funds” to attract foreign investment.

The purpose of an “out” strategy is to establish outposts in developed countries to be charge of research and consulting. The Korea Research Council of Fundamental Science & Technology, Korea Research Council for Industrial Science & Technology, New Drug Development Support Center, Korea Health Industry Development Institute and the Korea Trade-Investment Promotion Agency (KOTRA) are expected to jointly establish an institute in Europe and the United States.

This outpost plays a leading role in: R&D in conjunction with the developed markets, achievement and commercialization of R&D, attracting foreign experts, and networking within the local bio-pharmaceutical industry.

Considering that it is not easy for many foreign experts ― including Koreans ― to immigrate to Korea, overseas bases are relatively efficient in attracting talented workers. Especially for R&D planning, and marketing and commercialization, which must closely study the market, the number of experts is limited and the related expertise can be found only when near to the market.

It is important to foster global expertise by dispatching Korean workers overseas to learn about foreign companies, regulations and form a global network. Having a base in advanced countries can provide information and knowledge networks to Korean companies and increase the possibility of successfully entering global markets.

Lastly, the “bridge” strategy is a systematic network with Korean associations and societies in advanced countries. Building databases of overseas human resources for each sector will facilitate employment or information exchanges between Korean experts abroad and Korean agencies. In addition, sponsorship is necessary to consistently maintain and activate Korean societies and associations abroad. Since it is difficult to ensure the stability of associations with the current individual sponsor channels, the government should provide funds to support their consistent and reliable activities. In addition, supporting competent people who return to Korea is required so that they can maintain and expand the global networks. Recently, some experts who had been working in foreign multinational companies returned to Korea and began holding meetings to exchange their information and experiences. Now, support for these kinds of activities can provide an opportunity for returned experts to complement each other in expanding their global and local networks.

By Kim Hyungjoo, Seok-hyun Kim and Kim Seok-kwan

• Kim Hyungjoo is an associate research fellow at Science & Technology Human Resources Policy Division of Science and Technology Policy Institute in Seoul.

She has worked on human resource development and higher education, especially the role of policies and regional dimensions.

She can be reached at hjkim@stepi.re.kr

• Kim Seok-kwan is an associate research fellow at the New Growth Engines Research Center of the Science and Technology Policy Institute in Seoul.

His research focus has been on sectoral innovation systems, especially in the biopharmaceutical sector, and on technology management and innovation

studies. He can be reached at kskwan@stepi.re.kr

• Kim Seok-hyeon (Ph.D.) has the same position as the above author. His research area is statistics and indicators of science, technology, and innovation.

Recently, he, with his fellows of STEPI, published “Science, Technology, Innovation Indicator Study: Focusing on Firms.”

He joined STEPI in 2005 as soon as he finished his Ph.D. in economics at the University of Notre Dame (U.S.).

He can be reached at skim@stepi.re.kr

To bring back and utilize human resources that have gone overseas has been a goal of companies and governments of developing countries for a long time.

This is because these highly skilled human resources, who have world-class ability, can play a very important role in a company’s growth and national development. Therefore, if they remain abroad, their countries will suffer a “brain drain.”

Recently, highly skilled migrants from some developing countries have made vital contributions to the industrial development and economic growth of their homelands. They have built knowledge networks between their home countries and their new countries of residence, which have been increasingly significant in recent knowledge-based economies.

Thus, a “brain circulation” model that takes advantage of human resources abroad to build global knowledge networks has been given attention by most developing countries as a new strategy.

New argonauts

A typical example of this model is shown in the IT industries in Taiwan and India. In Taiwan, skilled workers who were educated or worked in the Silicon Valley returned to their home country, launched IT parts companies in the Hsinchu Science Park and grew these companies fast, supplying their manufactured parts to U.S. assembly companies. The cluster that formed as a result was important to the development of Taiwan’s IT industry. The global network that these workers established played an important role in this process. Consequently, the IT industry in Taiwan was able to enter the international market through the global knowledge networks that these workers were part of, and Silicon Valley’s venture system was transplanted at the same time, boosting Taiwan’s venture ecosystem.

The IT industry in India got its start while supplying simple services such as software coding to advanced countries. Highly skilled engineers who were educated or worked abroad returned to India, improved the level of IT services, and expanded the scope so that it played a fundamental role in creating worldwide software companies in India. IT companies such as Wipro have enhanced the knowledge network with markets in advanced countries through returning skilled workers and have entered the U.S. market.

In addition, some Taiwanese and Indian businessmen set up companies or local offices both in the U.S. and their home countries.

Saxenian (2006) called them the “New Argonauts,” to indicate the skilled workers from developing countries who live abroad and build knowledge networks in various ways between advanced countries and developing countries, which contribute to industrial development in their home country.

The establishment of global knowledge networks by these workers has developed domestic industries and upgraded them to the global level.

Global networks

Biotech and pharmaceutical industries recently showed the same phenomenon that Saxenian found in the IT industry. WuXi PharmaTech (WuXi) in China, for example, is a contract research organization (CRO) that supplies the chemicals that are necessary in drug discovery, and it has recently grown rapidly and changed the landscape of the CRO market.

This company continues to grow, almost doubling annually since its establishment in 2000, and it has grown into a large enterprise with 4,135 employees as of the end of 2009 (3,230 research staff) and sales of $270 million (net sales of $5.3 billion).

The reason WuXi was able to achieve rapid growth was due to the capabilities of those familiar with global standards, combined with the capabilities of scientists in China, which made it possible to deliver high quality services at a low price.

WuXi was founded by Dr. Ge Li who received a Ph.D. in organic chemistry from Columbia University and served eight years at Pharmacopeia in the United States. It employs over 100 scientists who were educated and had work experience from the United States.. Knowledge networks created by the scientists who returned home from the U.S. played an important role in the growth of WuXi.

Since the 1980s, global knowledge networks have developed in the pharmaceutical industry. Large pharmaceutical companies in advanced countries faced problems with R&D productivity and they looked externally for sources of innovation. Despite an increase in research funds, fewer new drugs are released every year, and large pharmaceutical companies in advanced countries have tried to reduce their research funds and raise R&D performance by way of outsourcing non-core R&D activities and licensing-in drug candidates from outside. This process has brought venture companies and CROs to supply promising drug candidates.

It is noteworthy that increasing numbers of bio venture companies and CROs in developing countries have become partners with global pharmaceutical companies as their level of science and technology has risen.

In the background of the expanding role of developing countries in the world’s pharmaceutical industries, as shown in the case of WuXi, the transnational knowledge community that has formed between developed countries and developing countries plays a critical role.

Transnational knowledge communities in Korea

In Korea, since 2005, dozens of the leading scientists who worked in the U.S. pharmaceutical industry returned and were recruited as chiefs of research institutes in Korea, and they have had a positive impact. Green Cross, Daewoong Pharmaceutical, ChoongWae Pharmaceutical, and Yuhan Corporation have recruited some of the United States’ leading researchers as R&D chiefs. However, the number of researchers brought in is small compared to China and India, and their impact on the pharmaceutical industry in South Korea is limited.

To investigate any possibility as to whether or not the Korean biotech and pharmaceutical industries can grow by taking advantage of skilled Korean workers abroad, STEPI carried out a survey with Korean scientists who are active in the U.S. biotechnology and pharmaceutical industry. Currently, more than 500 Korean scientists work in the U.S. for companies in the biotechnology and pharmaceutical fields.

They organized Korean associations such as the Korean American Society in Biotech and Pharmaceuticals, the Bay Area Korean-American Scientists Society in Biotechnology and Pharmaceuticals, and the BioPharma Association to exchange information, network, etc. The number of members in these organizations combined is about 700.

Additionally, the Korean Life Scientists in the Bay Area and the New England Bioscience Society are Korean associations that consist mainly of a total of 700 university professors, researchers and students (Table 1). A total of 214 people responded to the survey that was conducted with these associations and 57 of these respondents worked for companies.

In the following table, the opinions of the 57 respondents were analyzed.

First, when asked about the 10-year outlook for the biotechnology and pharmaceutical industries in Korea, the respondents were very negative. They were less negative on the 20-year outlook and it was thought that the industry would grow slightly. The reasons cited were: negative prospects for the development of Korea’s biotechnology and pharmaceutical industries; lack of experienced workforce, especially director-level research staff.

Meanwhile, Respondents were highly interested in getting a job in Korea and showed a strong willingness to work. Sixty percent of the respondents expressed interest in the possibility of working in Korea, and if already employed in Korea, they preferred working in public sector enterprises. However, the expected barriers while working in Korea included low funding levels, the rigid organizational culture of Korea and relatively low wage levels.

When the Korean government or agencies established local institutions in the United States, the willingness to work was 75 percent ― higher than that of working in Korea. Regarding a preferred employer, most respondents preferred companies and government-affiliated research institutions but respondents who worked in universities and public institutes showed high preferences for government-affiliated research institutions.

For job types, the majority of respondents preferred research work (55 percent), but planning services (35.3 percent) also showed significant numbers.

Looking at how the government supports the network of overseas workers, the respondents preferred the support of overseas Korean professional networks, overseas expansion of Korean firms and entrepreneurship, establishment of overseas offices for biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies, and Korean government participation in R&D industry planning and assessment, while preferences for a plan to attract domestic workers was relatively low. In terms of support for professional societies and associations, sponsors (33.3 percent) or database services for Korean professionals in the United States (28.1 percent) were preferred (see Figure 6).

Building global knowledge networks in Korean biotechnology and pharmaceutical Industries

The measures to establish the global knowledge network can be divided into an “in” strategy that attracts overseas workers and institutions, an “out” strategy to establish a base abroad, and a “bridge” strategy to link the domestic and international networks. Above all, the “in” strategy needs to attract leading overseas research institutes.

The government should coordinate and support plans to attract at least three or four leading overseas research institutes which employ a sizable number of researchers. Currently, except for the Institute of Pasteur Korea, and there have been few foreign research institutes that conduct R&D in Korea.

Local governments are also very interested in attracting renowned research institutes, however, they are likely to have uncertain budgets and no long-term visions for such a strategy. In addition, the international research centers that the government supports need to integrate the advanced systems and advantages of Korea. The government needs to establish a vision and commit to drawing in three or four sizable research institutes, and it should plan a matching fund with local governments.

Second, it is necessary to recruit globally experienced and skilled researchers to work for publicly supported organizations specialized in biotechnology and pharmaceuticals. For example, the New Drug Development Support Center located in the High-Tech Medical Complex that is being established acts as a government institute to support translational research that is necessary for the domestic biotechnology and pharmaceutical industries. The Center needs experienced overseas professionals who have worked at multinational companies and have global contacts.

Third, it is necessary to plan joint R&D projects among Korean venture companies and biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies in advanced countries.

Similar to the Israel-U.S. Binational Industrial Research and Development Foundation program that was established to absorb U.S. capital and market information, a joint R&D program between U.S. companies and Korean institutions (affiliated institutes, and ventures, including corporations) can be developed. Through such a program, companies in advanced countries could be provided an opportunity to conduct R&D more aggressively in Korea and take advantage of Korea as their R&D base.

Based on this network, there should be support to attract investment from advanced countries and also support for Korean professionals who have experience in advanced countries, to establish venture companies using the knowledge networks between Korea and advanced countries.

Fourth, a fund for investments in Korean bio-venture in collaborations with venture capitals in advanced countries should be created. A successful example of such is the Yozma Group in Israel that manages venture capital funds. If Korean ventures attract investment from advanced countries (multinational corporations or venture capital) then Korean fund will match for it. The Korean government should create a “fund of funds” to attract foreign investment.

The purpose of an “out” strategy is to establish outposts in developed countries to be charge of research and consulting. The Korea Research Council of Fundamental Science & Technology, Korea Research Council for Industrial Science & Technology, New Drug Development Support Center, Korea Health Industry Development Institute and the Korea Trade-Investment Promotion Agency (KOTRA) are expected to jointly establish an institute in Europe and the United States.

This outpost plays a leading role in: R&D in conjunction with the developed markets, achievement and commercialization of R&D, attracting foreign experts, and networking within the local bio-pharmaceutical industry.

Considering that it is not easy for many foreign experts ― including Koreans ― to immigrate to Korea, overseas bases are relatively efficient in attracting talented workers. Especially for R&D planning, and marketing and commercialization, which must closely study the market, the number of experts is limited and the related expertise can be found only when near to the market.

It is important to foster global expertise by dispatching Korean workers overseas to learn about foreign companies, regulations and form a global network. Having a base in advanced countries can provide information and knowledge networks to Korean companies and increase the possibility of successfully entering global markets.

Lastly, the “bridge” strategy is a systematic network with Korean associations and societies in advanced countries. Building databases of overseas human resources for each sector will facilitate employment or information exchanges between Korean experts abroad and Korean agencies. In addition, sponsorship is necessary to consistently maintain and activate Korean societies and associations abroad. Since it is difficult to ensure the stability of associations with the current individual sponsor channels, the government should provide funds to support their consistent and reliable activities. In addition, supporting competent people who return to Korea is required so that they can maintain and expand the global networks. Recently, some experts who had been working in foreign multinational companies returned to Korea and began holding meetings to exchange their information and experiences. Now, support for these kinds of activities can provide an opportunity for returned experts to complement each other in expanding their global and local networks.

By Kim Hyungjoo, Seok-hyun Kim and Kim Seok-kwan

• Kim Hyungjoo is an associate research fellow at Science & Technology Human Resources Policy Division of Science and Technology Policy Institute in Seoul.

She has worked on human resource development and higher education, especially the role of policies and regional dimensions.

She can be reached at hjkim@stepi.re.kr

• Kim Seok-kwan is an associate research fellow at the New Growth Engines Research Center of the Science and Technology Policy Institute in Seoul.

His research focus has been on sectoral innovation systems, especially in the biopharmaceutical sector, and on technology management and innovation

studies. He can be reached at kskwan@stepi.re.kr

• Kim Seok-hyeon (Ph.D.) has the same position as the above author. His research area is statistics and indicators of science, technology, and innovation.

Recently, he, with his fellows of STEPI, published “Science, Technology, Innovation Indicator Study: Focusing on Firms.”

He joined STEPI in 2005 as soon as he finished his Ph.D. in economics at the University of Notre Dame (U.S.).

He can be reached at skim@stepi.re.kr

![[Herald Interview] 'Amid aging population, Korea to invite more young professionals from overseas'](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/24/20240424050844_0.jpg&u=20240424200058)