Two hundred years ago, Hans Christian Anderson was born in the town of Odense, Denmark. From “The Snow Queen,” “The Little Match Girl” to “The Little Mermaid” and “The Ugly Duckling,” his legacy of children’s literature is timeless worldwide.

On Oct.1, in commemoration of the 200th year anniversary of Anderson’s birth, the 5th Nami Island International Book Festival kicked off on Nami Island in Chuncheon, Gangwon Province. This year, renowned children’s writers and illustrators from 22 countries have collaborated on a special project called “Peace Story,” an anthology of children’s short stories with an emphasis on peace.

On Oct.1, in commemoration of the 200th year anniversary of Anderson’s birth, the 5th Nami Island International Book Festival kicked off on Nami Island in Chuncheon, Gangwon Province. This year, renowned children’s writers and illustrators from 22 countries have collaborated on a special project called “Peace Story,” an anthology of children’s short stories with an emphasis on peace.

“Peace, democracy and tolerance are the leading ideas for children,” said Christiane Raabe, Director of the International Youth Library in Munich, Germany, who visited Seoul for the festival. “Peace can have different meanings for different countries, and kids who have to bear unfortunate situations.”

Three writers and illustrators from different cultural and historical backgrounds talked to The Korea Herald about their thoughts on peace and what it means to convey its meaning to their young readers around the world.

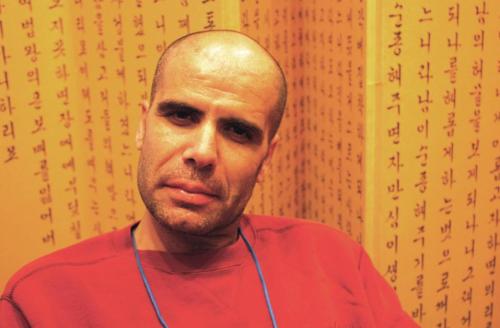

Mohammad Amous Illustrator / Palestine

To Palestanian illustrator Mohammad Amous, war is a reality. Born in war-torn Jerusalem, Amous was sent to a residential school as a child. “I missed a lot of my childhood,” the artist said. “I missed the real moments of fun the ordinary life, having dinner with your family, getting gifts and mingling with your cousins I missed all of that.”

Having lived through Palestine’s tense political climate against Israel, the word “peace” is deeply linked to the very matter of survival, Amous said. “Whether you want it or not, and doesn’t matter how old you are, political situations always affect you,” he said. “If war becomes your daily life, it’s like a dream to live in a peaceful situation.”

Amous draws and paints for children because he was always aware of the child within him. “I don’t want to complicate or sophisticate things,” he said. “I am trying to simplify things through my art. I’d like say and give things their pure meanings.”

Always using colorful tones and drawing cheerful faces, Amous avoids using dark colors as much as possible. “There is enough dark stuff in the world,” he said. “Our kids don’t need any more dark colors.”

The isolated environment of the residential school he attended made him realize how important it is to be exposed to the outside world. “I didn’t know what other kids outside the school were like,” he said. “But you need to know. You need to see the others to understand both yourself and the rest of the world.”

Amous is holding an artistic workshop during this festival, called “Dream of Hope,” where kids will sleep on a large piece of paper while others draw around their bodies. “I’ve designed the workshop so kids can understand the others in an artistic way,” he said.

“This Earth is made for everyone,” he continued. “We have everyone else to share it. I want our children to know that.”

Erfan Nazarahari Writer / Iran

Erfan Nazarahari from Iran writes about complex matters: spirituality, mankind, mysticism, love and unity. But she does it well, especially for kids.

“Childhood is beauty and peace,” said the writer, who contributed her story “A Heart Bigger Than The World” to this year’s project, “The Peace Story.”

The fantasy story depicts a child who is about to be born. She travels and meets many people before she gets thrown into the world. But when she is finally born, she realizes something that’s painful: She’s left her heart behind. And another word for that heart? Love.

Hence, the girl will search for that love throughout her life time. And in reality, many struggle to find it too.

“Some might find it hard to see why this story is about peace,” said Nazarahari. “But the message is simple try to love everybody and everything. Practice loving. There is nothing like love that’s more crucial in making peace.”

Nazarahari is known for her use of poetic language that is artistically simple and concise. She uses such language for children to better their understanding on matters that she values.

“Everyone has a child inside them,” she said. “Life is the growth of that inner child.”

Martin Auer Writer / Austria

Austrian writer Martin Auer thinks children are philosophers.

“They ask questions like ‘Why is the sky blue?’ and ‘Why do people die?’” the writer said. “And when they grow up, they stop being such philosophers.”

His contribution to the Peace project, “When the Soldiers Came” is certainly for philosophers, those who are willing to read between the lines. There is a war, politics, distribution of insufficient goods, and the victims. Though written for children, the story does not sugarcoat the truth about wars.

“It is not enough to tell children that war is bad and peace is nice,” the writer said. “We all know that. Just by being nice and tolerant we cannot prevent wars.”

He stressed that an individual has almost no say once he gets involved in a war, and is often victimized by the pursuit of what’s good for the majority. “My goal is to explain the mechanics,” he continued, “about how groups work differently from single persons.”

“If you don’t know the mechanics, you can’t build a car,” Auer said. “If you don’t change the military drills, you can’t prevent wars.”

By Claire Lee (clairelee@heraldcorp.com)

![[Exclusive] Korean military set to ban iPhones over 'security' concerns](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050599_0.jpg&u=20240423183955)

![[Graphic News] 77% of young Koreans still financially dependent](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/22/20240422050762_0.gif&u=)

![[Pressure points] Leggings in public: Fashion statement or social faux pas?](http://res.heraldm.com/phpwas/restmb_idxmake.php?idx=644&simg=/content/image/2024/04/23/20240423050669_0.jpg&u=)