뉴스속보 상세보기

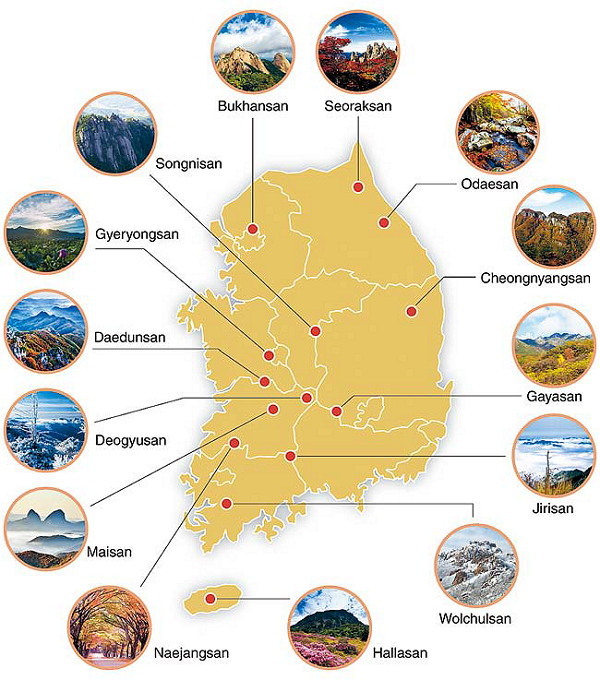

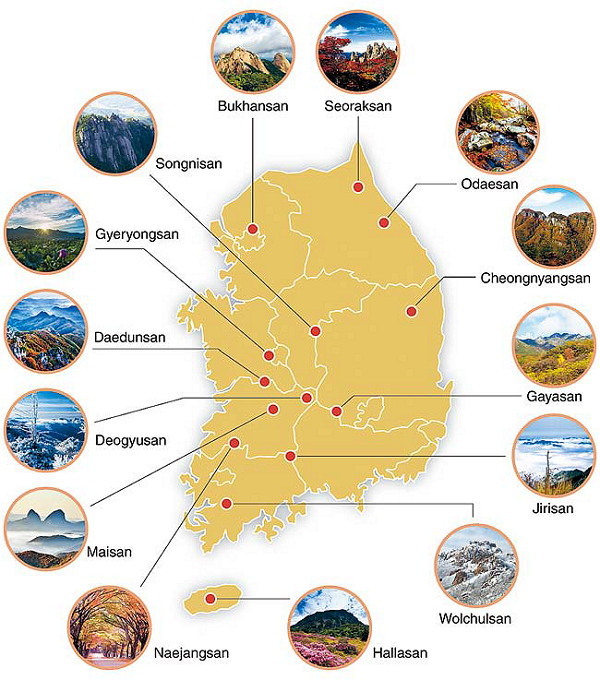

It’s hard to say exactly how many mountains there are in Korea, partly because there are so many of them. Former Korea Herald columnist Gary Rector notes, “There’s no real way to delineate a mountain (here) since they all run together in ranges. Some mountains even have more than one name, depending on where you look at them from.” Most are part of the Taebaek Range, along the east coast, and its many offshoots.

The country is so rugged that even the capital city has no fewer than a dozen peaks, or high hills, of 200 meters or taller. Other major cities here are also circled, pocked or fringed with mountains. Whether accessible or remote, though, just about every high point in the country has paths that follow its streams and ridges up to the top. Many still bear the legacies of the Korean War in the form of trenches, foxholes and sentry boxes, sometimes right next to stone fortresses built as long as 1,000 years ago.

Of South Korea’s mountains, 16 have been named national parks and 17 have been made provincial parks, mainly due to historical significance, scenic beauty or natural value. While the officially sanctioned peaks are unlikely to disappoint, plenty of undesignated mountains are also worth a climb.

Many believe that fall is the best time to visit Korea’s hill country ― for crisp, clean air and views of maple leaves turning gold, crimson and burnt orange. Mount Naejangsan National Park is particularly famous here for its autumn foliage, and its ridge, which almost describes a full circle, is packed with hikers intoxicated by the colors at this time of year. Other popular fall destinations include mountains close to urban centers and Korea’s loftiest retreats, Mounts Seoraksan, Jirisan and Hallasan.

The big three

By common consensus, the most visually stunning national park in the country is Mount Seoraksan on the east coast, the companion piece of North Korea’s Mount Geumgangsan, which is only 55 kilometers north as the crow flies.

But while the crows and magpies have no trouble reaching Seoraksan’s pinnacles and lofty pine trees, hikers need the better part of a day to reach Daecheongbong Peak, the third-highest in the South at 1,708 meters.

As there are several shelters near the top, many spend the night and wake up before dawn for a view of the sun rising from the East Sea horizon, or from out of a sea of clouds.

From Sokcho, Gangwon Province, a 30-minute bus ride brings one to the park entrance. Among the highlights on this side of the park are the easy-to-reach Biseondae ― an emerald-green pool overshadowed by cliffs and towering peaks. The shelf of granite along the stream has, over the ages, become a masterpiece of carved calligraphic graffiti, and for those proceeding further up the valley the restaurant here offers the last chance to order gamja jeon and makgeolli (savory potato pancake and unrefined rice wine).

Among the shelters, Jungcheong is closest to the summit. The National Park Service advises that bookings be made in advance, and though the reservation system is out of order on the English version of the website, the process can be accomplished in Korean at reservation.knps.or.kr. Overnighting costs 8,000 won ($7.50) during peak season and 7,000 won from early winter to early spring. A warning, though: All the spots are likely to have been snatched up for the weekends this fall. Camping is generally not allowed in the national parks.

Straddling three southern provinces, Mount Jirisan was declared Korea’s very first national park in 1967 and is still the country’s largest. That was only 12 years after the last communist guerillas were rooted out from the area ― not when the Korean War Armistice Agreement was signed, but two years thereafter.

Due to its sheer size, Jirisan was chosen as the home for several Asiatic black bears (known here as half-moon bears) when they were reintroduced into the wild in 2004.

The park is essentially a long, winding ridge, stretching 25.5 kilometers east-west from Cheonwangbong Peak, South Korea’s second-highest at 1,915 meters, to Nogodan. Cheonwangbong, meaning Heavenly King, is a fairly common name for Korean peaks ― namesakes can be found at Mounts Gyeryeongsan, Songnisan and Seonunsan.

Starting from Nogodan makes for an easy approach, as buses from Namwon, North Jeolla Province, stop just below the ridge. To attempt the steep hike to Cheonwangbong, catch a bus from Jinju, South Gyeongsang Province.

Jirisan has even more shelters than Seoraksan (eight and five, respectively). The only other national park with such full-scale facilities is Deogyusan.

Rounding out South Korea’s top three mountains is Mount Hallasan, the centerpiece of Jejudo Island. Slightly taller than Cheonwangbong, the 1,950-meter volcano has remained dormant for about a millennium. The five routes up, of varying distance and difficulty, lead to Baengnokdam, a shallow pond in the crater. Fortunately there are rope railings to hold onto, as the wind can be ferocious up top.

Ocean views are often blanked out by cloud cover, though it’s not as stubbornly foggy as Mount Baekdusan, a volcano on the North Korea-China border whose stunning crater lake Cheonji is rarely in the mood to be photographed.

Cloud bridges

Aside from autumnal colors and peaks that make up for shortness with steepness, Korea’s mountains offer a selection of novelties like death-defying suspension bridges, strangely shaped rocks and mesmerizing sea views.

Those with a fear of heights may want to avoid the suspension bridge (called a “cloud bridge”) at Wolchulsan National Park, South Jeolla Province. Spanning a deep gulf, the vertigo is offset by a view of the rice fields from which Wolchulsan rises abruptly.

South Chungcheong Province’s Daedunsan Provincial Park also has a morbidly attractive cloud bridge, as does Cheongnyangsan Provincial Park in North Gyeongsang Province, which is still one of the lesser-visited mountains almost 500 years after Confucian scholar Yi Hwang wrote in a poem, “Only I and the seagulls know / Cheongyangsan’s 36 peaks.”

Hikers less inclined to sweat it out on the trails can ride cable cars part way or all the way up at Duryunsan, Geumosan and Palgongsan provincial parks; Seoraksan National Park; Mount Geumjeongsan in Busan; and, of course, Mount Namsan in Seoul.

Strange rocks

For oddly weathered rocks, Wolchulsan National Park takes the cake. Not only is it clustered with boulders and peaks that look like blobs and candlewax drippings, but it also lays claim to a stone and a cave with shocking anatomical resemblances.

In North Jeolla Province, the twin peaks of Maisan Provincial Park look like a pair of horse’s ears, as the name suggests. The taller of the two (686 meters high) can be climbed by hikers thanks to stairs, but the real attraction is Tapsa Temple, between the two “ears,” where a mysterious collection of over 80 stone pagodas that were built by one man in the late 19th century remain standing.

While in Seoul such urban prominences as Mount Inwangsan and Mount Ansan are the resting places of warped and hollowed boulders revered by shamanists, the most famous rock might be Insubong Peak. Just out of city limits in Bukhansan National Park, the cone-shaped peak can be seen on a clear day as part of the Mount Samgaksan triad. While Bukhansan is the most-visited national park in the world per square meter, according to Guinness World Records, Insubong is probably the country’s most-trafficked rock-climbing destination. Those hoping for an early climb up one of its 58 routes stay the night at Insu Shelter or at the camping area nearby.

Ocean views

Aside from Seoraksan and Hallasan, there are several other Korean mountains famous for ocean views from high prospects. Mount Manisan is perched at the southern end of Ganghwado Island, near Incheon, with a view down a curved slope of the West Sea and its smattering of islands and mud flats. Though the peak is only 469 meters high, it’s the site of the ancient stone altar of Chamseongdan. Some say that, in one form or another, the altar has been in use since Dangun, the mythical founder of Korean civilization, made offerings here 4,000 years ago. An annual ceremony is conducted at this open-air altar on National Foundation Day, as well as at a similar altar on Mount Taebaeksan, Gangwon Province.

For potentially clearer views, the South Jeolla Provincial Parks of Mounts Duryunsan and Cheongwangsan near Korea’s Land’s End provide magnificent views of the peninsula’s southwest archipelago.

By Matthew C. Crawford (mattcrawford@heraldcorp.com)

The country is so rugged that even the capital city has no fewer than a dozen peaks, or high hills, of 200 meters or taller. Other major cities here are also circled, pocked or fringed with mountains. Whether accessible or remote, though, just about every high point in the country has paths that follow its streams and ridges up to the top. Many still bear the legacies of the Korean War in the form of trenches, foxholes and sentry boxes, sometimes right next to stone fortresses built as long as 1,000 years ago.

Of South Korea’s mountains, 16 have been named national parks and 17 have been made provincial parks, mainly due to historical significance, scenic beauty or natural value. While the officially sanctioned peaks are unlikely to disappoint, plenty of undesignated mountains are also worth a climb.

Many believe that fall is the best time to visit Korea’s hill country ― for crisp, clean air and views of maple leaves turning gold, crimson and burnt orange. Mount Naejangsan National Park is particularly famous here for its autumn foliage, and its ridge, which almost describes a full circle, is packed with hikers intoxicated by the colors at this time of year. Other popular fall destinations include mountains close to urban centers and Korea’s loftiest retreats, Mounts Seoraksan, Jirisan and Hallasan.

The big three

By common consensus, the most visually stunning national park in the country is Mount Seoraksan on the east coast, the companion piece of North Korea’s Mount Geumgangsan, which is only 55 kilometers north as the crow flies.

But while the crows and magpies have no trouble reaching Seoraksan’s pinnacles and lofty pine trees, hikers need the better part of a day to reach Daecheongbong Peak, the third-highest in the South at 1,708 meters.

As there are several shelters near the top, many spend the night and wake up before dawn for a view of the sun rising from the East Sea horizon, or from out of a sea of clouds.

From Sokcho, Gangwon Province, a 30-minute bus ride brings one to the park entrance. Among the highlights on this side of the park are the easy-to-reach Biseondae ― an emerald-green pool overshadowed by cliffs and towering peaks. The shelf of granite along the stream has, over the ages, become a masterpiece of carved calligraphic graffiti, and for those proceeding further up the valley the restaurant here offers the last chance to order gamja jeon and makgeolli (savory potato pancake and unrefined rice wine).

Among the shelters, Jungcheong is closest to the summit. The National Park Service advises that bookings be made in advance, and though the reservation system is out of order on the English version of the website, the process can be accomplished in Korean at reservation.knps.or.kr. Overnighting costs 8,000 won ($7.50) during peak season and 7,000 won from early winter to early spring. A warning, though: All the spots are likely to have been snatched up for the weekends this fall. Camping is generally not allowed in the national parks.

Straddling three southern provinces, Mount Jirisan was declared Korea’s very first national park in 1967 and is still the country’s largest. That was only 12 years after the last communist guerillas were rooted out from the area ― not when the Korean War Armistice Agreement was signed, but two years thereafter.

Due to its sheer size, Jirisan was chosen as the home for several Asiatic black bears (known here as half-moon bears) when they were reintroduced into the wild in 2004.

|

| Piagol valley in Jirisan Mountain (Yonhap) |

The park is essentially a long, winding ridge, stretching 25.5 kilometers east-west from Cheonwangbong Peak, South Korea’s second-highest at 1,915 meters, to Nogodan. Cheonwangbong, meaning Heavenly King, is a fairly common name for Korean peaks ― namesakes can be found at Mounts Gyeryeongsan, Songnisan and Seonunsan.

Starting from Nogodan makes for an easy approach, as buses from Namwon, North Jeolla Province, stop just below the ridge. To attempt the steep hike to Cheonwangbong, catch a bus from Jinju, South Gyeongsang Province.

Jirisan has even more shelters than Seoraksan (eight and five, respectively). The only other national park with such full-scale facilities is Deogyusan.

Rounding out South Korea’s top three mountains is Mount Hallasan, the centerpiece of Jejudo Island. Slightly taller than Cheonwangbong, the 1,950-meter volcano has remained dormant for about a millennium. The five routes up, of varying distance and difficulty, lead to Baengnokdam, a shallow pond in the crater. Fortunately there are rope railings to hold onto, as the wind can be ferocious up top.

Ocean views are often blanked out by cloud cover, though it’s not as stubbornly foggy as Mount Baekdusan, a volcano on the North Korea-China border whose stunning crater lake Cheonji is rarely in the mood to be photographed.

|

| A view of one of the gates of Geumseong Mountain Fortress, on Mount Sanseongsan, South Jeolla Province (Matthew C. Crawford/The Korea Herald) |

Cloud bridges

Aside from autumnal colors and peaks that make up for shortness with steepness, Korea’s mountains offer a selection of novelties like death-defying suspension bridges, strangely shaped rocks and mesmerizing sea views.

Those with a fear of heights may want to avoid the suspension bridge (called a “cloud bridge”) at Wolchulsan National Park, South Jeolla Province. Spanning a deep gulf, the vertigo is offset by a view of the rice fields from which Wolchulsan rises abruptly.

South Chungcheong Province’s Daedunsan Provincial Park also has a morbidly attractive cloud bridge, as does Cheongnyangsan Provincial Park in North Gyeongsang Province, which is still one of the lesser-visited mountains almost 500 years after Confucian scholar Yi Hwang wrote in a poem, “Only I and the seagulls know / Cheongyangsan’s 36 peaks.”

Hikers less inclined to sweat it out on the trails can ride cable cars part way or all the way up at Duryunsan, Geumosan and Palgongsan provincial parks; Seoraksan National Park; Mount Geumjeongsan in Busan; and, of course, Mount Namsan in Seoul.

Strange rocks

For oddly weathered rocks, Wolchulsan National Park takes the cake. Not only is it clustered with boulders and peaks that look like blobs and candlewax drippings, but it also lays claim to a stone and a cave with shocking anatomical resemblances.

In North Jeolla Province, the twin peaks of Maisan Provincial Park look like a pair of horse’s ears, as the name suggests. The taller of the two (686 meters high) can be climbed by hikers thanks to stairs, but the real attraction is Tapsa Temple, between the two “ears,” where a mysterious collection of over 80 stone pagodas that were built by one man in the late 19th century remain standing.

While in Seoul such urban prominences as Mount Inwangsan and Mount Ansan are the resting places of warped and hollowed boulders revered by shamanists, the most famous rock might be Insubong Peak. Just out of city limits in Bukhansan National Park, the cone-shaped peak can be seen on a clear day as part of the Mount Samgaksan triad. While Bukhansan is the most-visited national park in the world per square meter, according to Guinness World Records, Insubong is probably the country’s most-trafficked rock-climbing destination. Those hoping for an early climb up one of its 58 routes stay the night at Insu Shelter or at the camping area nearby.

Ocean views

Aside from Seoraksan and Hallasan, there are several other Korean mountains famous for ocean views from high prospects. Mount Manisan is perched at the southern end of Ganghwado Island, near Incheon, with a view down a curved slope of the West Sea and its smattering of islands and mud flats. Though the peak is only 469 meters high, it’s the site of the ancient stone altar of Chamseongdan. Some say that, in one form or another, the altar has been in use since Dangun, the mythical founder of Korean civilization, made offerings here 4,000 years ago. An annual ceremony is conducted at this open-air altar on National Foundation Day, as well as at a similar altar on Mount Taebaeksan, Gangwon Province.

For potentially clearer views, the South Jeolla Provincial Parks of Mounts Duryunsan and Cheongwangsan near Korea’s Land’s End provide magnificent views of the peninsula’s southwest archipelago.

By Matthew C. Crawford (mattcrawford@heraldcorp.com)